Last month, Anne Dolamore of Grub Street Publishing very kindly sent me a new edition of Jane Grigsons’ classic, Good Things. Grub Street have reissued it because Jane Grigson highlighted and celebrated seasonal food, and seasonality, as Grub Street note, is ‘top priority of all those who take their eating and cooking seriously.’

First published in 1971, Jane says in the introduction to the original edition:

‘‘…I feel that delight lies in the seasons and what they bring us…the strawberries that come in May and June straight from the fields, the asparagus of a special occasion, kippers from Craster in July and August, the first lamb of the year from Wales. This is good food.’

She goes on:

‘The encouragement of fine food is not greed or gourmendise; it can be seen as an aspect of the anti-pollution movement in that it indicates concern for the quality of environment. This is not the limited concern of a few cranks.’

Anyone who’s had an email from me knows how much I revere Jane Grigson; I share a quote from her that remains my mantra;

‘We have more than enough masterpieces

What we need is a better standard of ordinariness.’

If you’ve read my stories you’ll see that I often quote from her extensive knowledge of food history and varieties.

Fifty four years ago she was highlighting that good food is for everyone. It’s still an uphill struggle.

Last November I wrote a guest post for

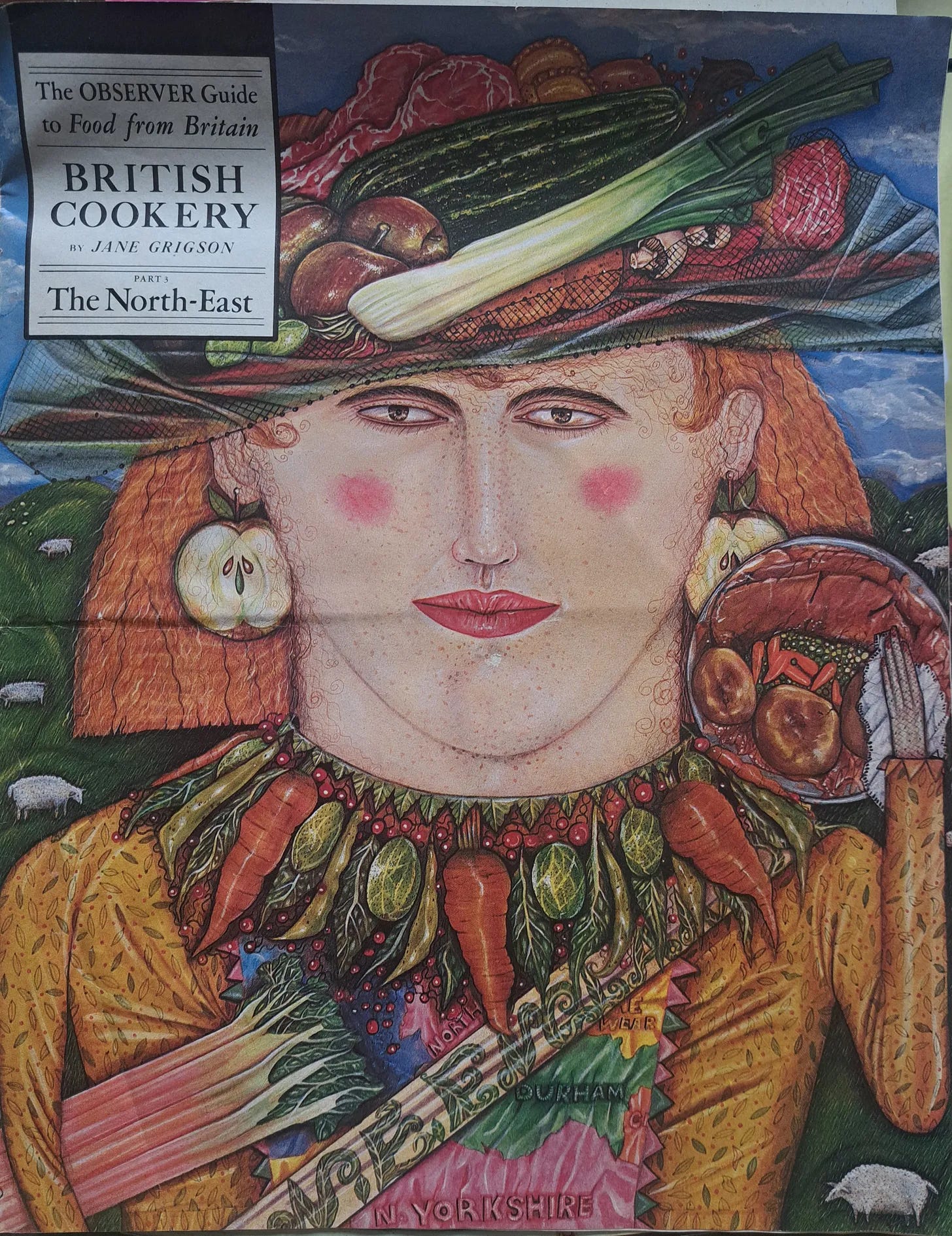

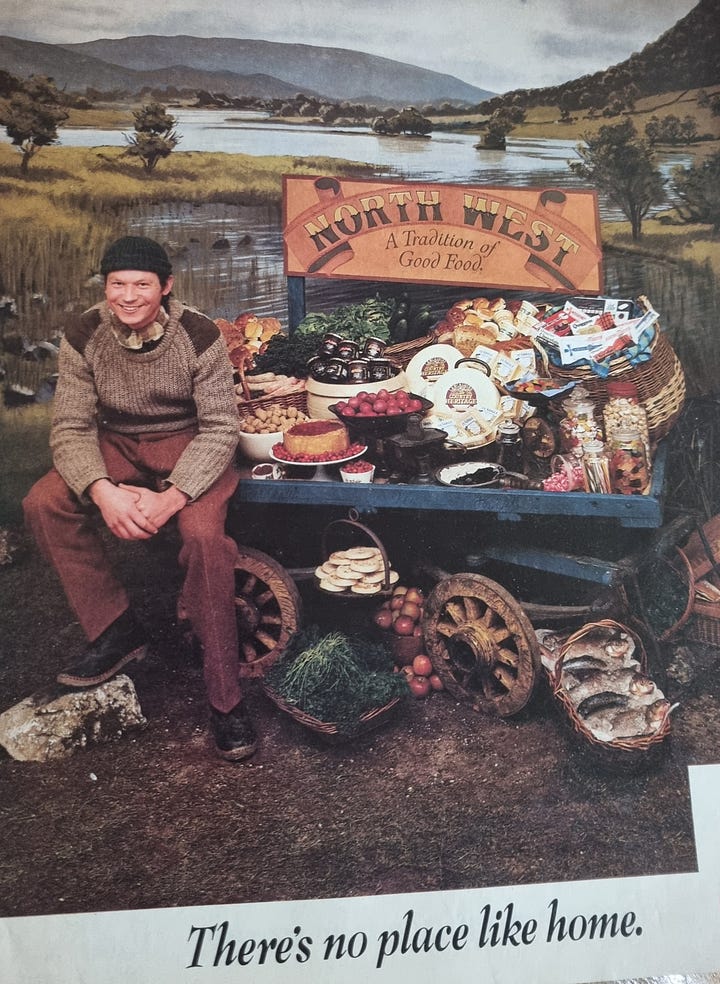

called Never Trust The Brownie Cookbook. I mentioned that in the 1970’s Jane Grigson wrote her guide to Food from Britain for The Observer newspaper. I’ve still got some of the pull outs. It was the first time that local food entered into the lexicon as something to be proud of, preserved and cherished.At the other end of the scale; At my grandparents house, I’d sit in the kitchen for hours, copying out recipes from Grandma’s Elizabeth Davids’ Italian Food. I don’t think I ever made it, but I loved the sound of apricot ice. The book took me on a journey to Italy, long before I’d travelled there.

I loved reading books by Elizabeth and Jane but it’s Jane I most often turn to, and Jane who feels like a warm aga on a cold day, whilst Elizabeth feels like her own work; Harvest of the Cold Months. Jane is as welcoming and down to earth as a glass of damson gin. Elizabeth, like a glass of chilled fino. Jane introduced me to wonderful words like bloater and kickshaw, and her curiosity and in-depth knowledge about food stories, fed and fired my own love for food history.

Elizabeth David came from a wealthy family and was sent to Paris and then Munich for her education.

She spent the 2nd world war in Italy, Greece and Egypt. Writing as a cookery journalist, her articles appearing in Harper’s Bazaar from spring 1949, evoking the memories of the foods she’d appreciated, in contrast to the austerity of post war Britain, still in the grips of food rationing.

Jane came from a working class North-East family. She spent the 2nd world war in Cumbria, and from there, went to Cambridge University. She worked in art galleries and publishing houses, and spent three months in Italy. She met poet Geoffrey Grigson whilst working at Thames and Hudson. After the birth of their daughter Sophie, Geoffrey and Jane bought a tiny cave house in Trôo in the Loir-et-Cher region of France. It was from here that her interest in food developed.

Her first book Charcuterie and French Pork Cookery (1967) was the fruit of four years’ research. The following year, Elizabeth David recommended Jane as cookery writer for the new colour magazine of the Observer newspaper.

Good Things is a collection of some of her articles. She said;

“This is not a manual of cookery, but a book about enjoying food.”

‘Being always grateful for the background of an unfailing larder, I feel that delight lies in the seasons and what they bring us’

Jane became a crusader for the foods of the British Isles, writing at a time when food from abroad was glamorous and adored, and UK food maligned and old fashioned. She championed natural and high welfare farming practices.

As Geraldine Holt says in her article about Jane;

‘Jane was particularly interested in English food and its past. She lamented that we had lost so much due to modernisation and industrial practices when, for almost all of man’s time on earth, he grew food naturally in a way that we now label as organic. Enlightened gardeners rarely waver from this traditional approach, and an increasing number of of farmers and horticulturists have recently adopted these methods. In her work Jane helped pioneer this campaign for unadulterated food which now has legions of supporters.’

In Good Things you’ll find chapters on meat and game, fish, vegetables, edible woodland mushrooms, fruit, dessert and fruit liqueurs. The book opens with a recipe for kippers for breakfast and paragraphs about smoked fish. In the vegetable chapter is her famous curried parsnip soup recipe. She writes about quince, gooseberries, prunes and walnuts. In the desserts section are recipes for coffee granita and Camembert ice cream.

Elizabeth and Jane were friends and admired each other’s work. In the introduction to Good Things, Jane recommends Elizabeth’s book, French Provincial cooking and I love that of the gooseberry sauces I mention below, one she gives is by Elizabeth David.

Although they both wrote beautifully, Elizabeth, I feel would pounce on you for using the wrong type of anchovy.

It’s Jane’s generosity, and down to earth character, her foibles, the feeling that she’s besides you at the kitchen table, encouraging you that wins me over. Although some of her instructions can be strict and to the point, I can still hear her saying, ‘it’s just a bit burnt, no-one will notice, it will still taste good.’

And whilst Elizabeth David brought the sunshine of the Mediterranean to the gloom of war starved Britain still on rations, it was Jane Grigson who brought us back our dignity and pride in the food that is still being championed here today.

If I had the choice of whose table to sit at, it would be Jane every time.

‘Anyone who likes to eat, can soon learn to cook well…. There’s no reason for not eating deliciously - and simply- all the time. So why don’t we? After all, in the eighteenth century our food was the envy of Europe. Why isn’t it now?’