Welcome to my 40th post on Substack. Hard to believe I’ve been writing every week for 40 weeks; I’m already thinking about my 50th post. This piece almost didn’t make it due to time constraints, the recent storm and a myriad other factors so as always, thank you for being here and reading my work.

If you’ve never commented or liked and shared a post, please do. It gives me a warm glow, knowing that my work is appreciated.

I always feel embarrassed mentioning this, but the best way to support me, if you think my work is worth it, is to press the buttons to upgrade to paid. Or gift a subscription! Thank you.

There aren’t too many guaranteed dates each year when a mass cull takes place but pre-Christmas is one of them. By mid December each year millions of turkeys face the chop to feed a tradition of feasting. Most turkeys have already said their last 'gobble gobble' by the 12th December.

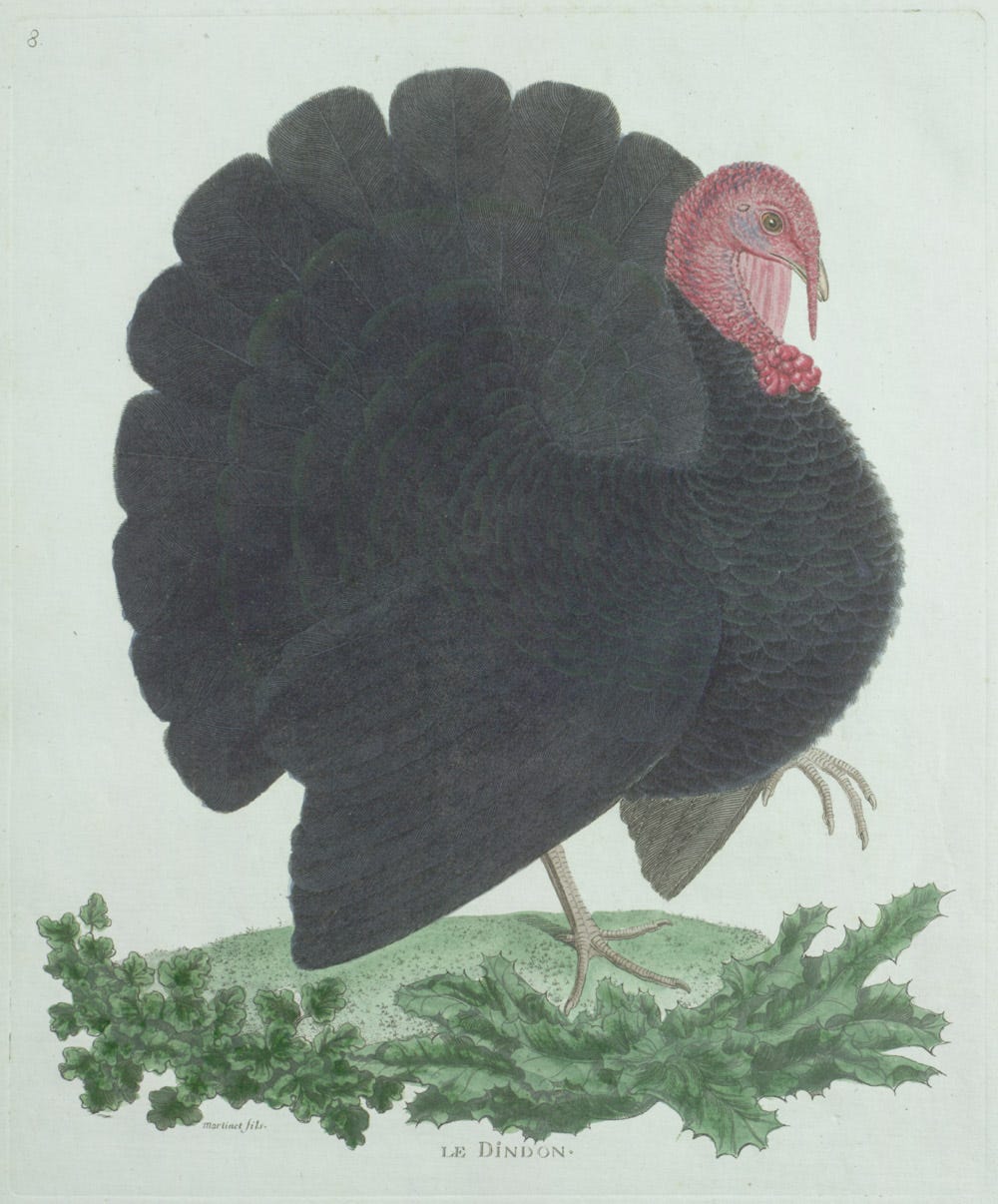

The first known illustration of a turkey in the UK dates to the 1550’s when William Strickland had a turkey added to his cost of arms. Strickland served as lieutenant to Sebastian Cabot the English explorer on a voyage of discovery to the New World and brought black turkeys back with him.

King Henry V111 was the first monarch to have turkey on his Christmas table amongst countless other viands. Throughout the 16th century, the popularity of turkey increased for those who could afford it, in line with the growth of turkey rearing, especially in eastern England and Norfolk, where there was good land, not too far from London.

Spare a thought for the turkeys of the 1700's that were herded for weeks (even months) from Suffolk and Norfolk down to Smithfield in Central London. It was common for farmers to start their journey in September. The feet of the birds were painted with hot tar and then dipped in sand or straw as protection before their long walk. By 1750 there were over 250,000 turkeys walking a few miles a day, in flocks of 100-1,000, foraging on berries, acorns, grass and corn an route.

Charles Dickens is supposed to have popularised turkey instead of the more common goose. All I remember thinking after reading A Christmas Carol is; why is the butcher open on Christmas Day? English Heritage have this to say;

‘Many people joined goose clubs to save up for their goose throughout the year. Like turkey, goose was in season in December – domesticated poultry was regarded as at its best in the winter, hence its association with Christmas. It was best roasted in front of an open fire, and those who couldn’t afford a roasting mechanism were known to use a piece of string, twisted round on itself, which would gradually untwist and retwist with the bird dangling vertically on the end. Otherwise, bakers, like many other food sellers, stayed open on Christmas morning, and their customers would bring their meat to be cooked in the huge bakers’ ovens.’

From the BFI in 1930, here’s the annual turkey auction in Attleborough in Norfolk, where prosperity is reflected in the two black Norfolk turkeys that adorn the town's sign.

Around 10 million turkeys are slaughtered in the UK for Christmas. The majority of the turkeys in the UK are reared indoors in large purpose-built sheds or converted farm buildings. Up to 25,000 birds can be housed in one building, with a tightly controlled environment, including lighting, temperature, and ventilation. They’ll never see daylight or get to range across a grassy meadow. They could be beak trimmed to stop them pecking each other, fed a diet to make them grow quickly, and injected with antibiotics. According to Compassion in World Farming, nearly 4 million turkeys are intensively reared indoors in Norfolk alone.

Bernard Matthew gave a rare interview in 1963, archived by the BFI. It shows the intensively reared birds from shed to chiller.

For organically reared turkeys, the limit is no more than 1,000 birds in a flock. No beak trimming, antibiotics, or growth promoters.

If you buy a bird from a trusted farmer, direct from the farm or farmers market, you’ll be able to ask questions about welfare standards and provenance.

For any free range poultry farmer, avian flu is a worry. In 2022 the UK lost 40% of the 1.4 million free range turkeys according to the British Poultry Council. This year the first outbreak has been announced with thousands of turkeys culled on a farm in Norfolk.

The reason a supermarket can sell a turkey so cheaply is the lifespan of the bird and how they’re fed and looked after. High welfare turkeys will be on a farm for around 6 months. Supermarket birds will be fed a high compound standard feed which means they will reach their required weight more quickly. They’ll be slaughtered at around 3 months without having had a chance to range outdoors, or to forage and develop muscles. As a result, they’ll lack the essential layer of fat under the skin. Chances are they won’t have been dry plucked, or game hung to tenderise them.

Even a free range supermarket turkey isn’t always as good as it sounds. The Cornish Food Box Company have this to say; ‘The stocking density is around half that of their battery counterparts, and while they are required to have access to the outdoors, the way they are raised and housed means that most will never venture outside. By having very large numbers of birds housed together makes it very difficult for birds to make their way outside. In this system, birds that have the potential to grow to 15kg are only taken to 5kg. That’s because this is a popular size for the Christmas table. They are processed before the bird reaches full maturity.’

The Traditional Farm Fresh Turkey Association have a list of accredited turkey farms on their website. If you’re in London, there’s a range of free range and organic farms selling at farmers market.

Jacob Sykes and Nick Ball have been farming poultry since returning to the family farm in 2009, at Fosse Meadows in Leicestershire. Their free-range turkeys are slow-grown to 6 months old. Like their chickens, geese and ducks, their turkeys are kept in small flocks to promote natural behaviour.

‘‘Some folks moan when they see mince pies in the shops during October, well we see turkeys in June!’’

Their day old turkey and geese chicks arrive in June. Once they start growing it’s a routine process of feeding, watering, checking for any illness but by October they are getting really big and their appetites are huge which mean large costs for the farm in grain. I visited Fosse and can confirm how curious turkeys are; they’ll happily run towards you and follow in packs, to peck at your clothing or boots!

‘‘Because all our poultry is free range they actually eat more than barn reared birds as they use lots more energy running around the farm. We only have bronze turkeys for flavour, kept in small flocks and they have a great diet of additive free cereals. It helps to give them a delicious taste and succulent meat texture.’’

From about the 4th December they start taking the turkeys. The day before, they’re put into a quiet barn. The turkeys are dispatched early in the morning when its still dark and the birds are sleepy and relaxed. They are then hung until just before Christmas, which give them excellent flavour and tenderises the meat. Many supermarket turkeys are gas sealed in a bag to keep them fresh for weeks rather than using traditional methods of keeping the meat fresh. Fosse’s birds are then eviscerated, dry plucked and dressed, the hearts and liver kept for stock and pate.

Fosse’s geese are on their farm for 6-7 months. They’re dry-plucked and hung for 7-10 days. They also sell free range ducks and their 3 star Great Taste award cockerels, slow grown to 112 days. Geese are not as popular in the UK as turkeys; with prices often similar to a turkey, and the fact that a goose won’t go as far as a turkey, they’re often not given a second thought.

The Traditional Farm fresh Turkey Association who promote welfare and quality to ensure the very best free range turkey say ‘ask your butcher how old the turkey is. The majority of birds are slaughtered as ‘teenagers’ (about 8-12 weeks), having been grown very quickly and cheaply. As a result, the flesh is effectively ’stretched’ and has no fat cover, resulting in meat that is often dry and coarse.’

Farmers they work with choose slower-growing breeds and rear them as free-range on their farms to full maturity – approximately 6 months. The turkeys are dry plucked, finished by hand, and then dry aged, (matured in chilled rooms) for at least seven days.

It's not an easy decision to make, especially if you’re on a tight budget but the advice as always is buy the best that you can afford. And place your order as soon as you can.

In the space of a few days I've had two messages to tell me that a farmer I've known has died. David Knipe, who has passed away following a tragic farm accident, you met in my piece on Barnard Castle farmers market. Knowledgeable and enthusiastic, he was clearly adored by customers, and loved talking to people. If you've not read the piece, about a third of the way down, please enjoy the audio clip of David explaining how to truss a chicken and why he calls it the Dolly Parton look. He was described as a living legend and I know he’s going to be a hard act to follow.

David Deme who has recently passed away was at the heart of Chegworth Valley farm in Kent. David & Linda Deme moved from owning a newsagents and taxi business in South London to farming, despite having no previous experience. They planted vegetables and sowed grain before planting orchards. Once they began to press their apples into juice, and found how quickly it sold, Chegworth Valley was born. They were at the very first farmers market in London in 1999 and have been a mainstay since then. Their children Ben and Charlotte grew up helping out on the market stalls.

Sadly David developed Parkinson's disease but it didn’t stop him helping out on the farm. The few occasions in the last few years when he came to run a farmers market stall it was a joy to see how many customers wanted to stop to talk to him. Ironically Chegworth has been in my thoughts lately, thinking ahead to articles I want to write next year. The Deme family have grown their farm business to the extent that you'll find bottles of their bright jewel coloured juice blends all over the UK. I have no doubt that Chegworth will continue to grow, with Ben and Charlotte at the helm, and Davids advice and wisdom in mind.

On television this week

Time and tide and buttered eggs wait for no man

The Box of Delights is a fantasy children's book by port laureate John Masefield. It remains one of my favourite books. Serialised by the BBC in 1984, it’s back on television this week for its 40th anniversary. Please forgive the early days television special effects, and dive into a magical Christmas story. For those of you out of range of viewing it, do please read the book. It’s full of ancient folk lore, talking rats, pagan heroes and satisfyingly bad baddies.

There's another way to support me if you think that my work is worth paying for and a monthly or yearly subscription isn't possible; I’m always delighted to receive A cup of coffee.

And do please share and like this post. That’s all it takes to get this piece more widely seen.

Thank you for writing such detailed, interesting articles. Love them!

Brilliant article. Thank you so much for introducing me to an excellent "crop" of farmers too. They make our world edible.