Playing gooseberry

Three gooseberry recipes, where fairies like to hide, and a gooseberry interlude with thorns.

I’ve had a change of heart about paywalls. Instead of putting a paywall into posts, I’m going to trial publishing posts for paid subscribers only, focusing on my recommendations. My market of the month, what’s in season, what I’m buying, cooking, reading. What I’ve made this month and more. As paid subscribers build I’ll start running regular zoom events to ask me anything, as long as it’s within my areas of expertise! I know that paywalls can be off-putting; I want to provide good value and insights alongside excellent writing.

Some of you are kind enough to tell me that you love how I write. What’s important to you when you read my posts? I know that many of you like to read on the farm pieces, deep subject dives, at market with food writers. and reports from markets. If more people choose to become paid subscribers, I can write more of these, and spend more time deep diving into subjects.

Writing on Substack is a joy but it’s also a job. I write about paying a fair price for a fair product and the same is true for writers. I’m happy to share my knowledge, and I put a lot of work into the pieces I write. Do let me know what you’d like me to cover.

Free posts will continue, two or three times a month instead of weekly. I appreciate every one of you who takes the time to read my posts and totally understand how saturated an inbox can become. I thank you most sincerely for being here with me.

If you’d like to support me by becoming a paid subscriber, I’m offering a 20% discount off your first years subscription for anyone who subscribes before 6th July.

Now, onto gooseberries before their season ends.

x Cheryl

Today; why gooseberries aren’t grapes, what a gooseberry bush really means, gooseberry history, where fairies favour to shelter, plus Jane Grigon’s gooseberry sauce to eat with fresh mackerel, and two delectable sweet gooseberry recipes.

Gooseberries have dagger like thorns, and aren’t afraid to use them, as I discovered to my cost last week.

It’s as if this season has been curated by Disney. Spring was more springier than I’ve seen it for many years. Now Summer is here, the seasons seem to be apologising for last years appalling behaviour, making up for it with a tumbling abundance.

Obviously we need rain. Farmers need rain. What we don’t need is last years slug & snail fest. Instead, this year we're having a buzzby Berkeley bee festival. We can't keep up with the number of bees we've seen, from buff tail bumbles to solitary leaf cutter bees, dizzy with drinking in all the nectar they can feast upon.

After last years dismal showing, it’s a good year for gooseberries. Sadly, they are not easy to find commercially, unless you visit a farmers market, or farm shop. I tried at five supermarkets and three greengrocers recently, out of curiosity, and only one stocked them (Waitrose). There’s still time as gooseberries are in season for a few months. Picking gooseberries needs patience and thick gardening gloves, except that I can never wear glove to pick fruit, so off they come, and that’s when the thorns go out of their way to find me.

I often explained to customers at farmers markets that a punnet of gooseberries weren’t grapes. It was amusing to read

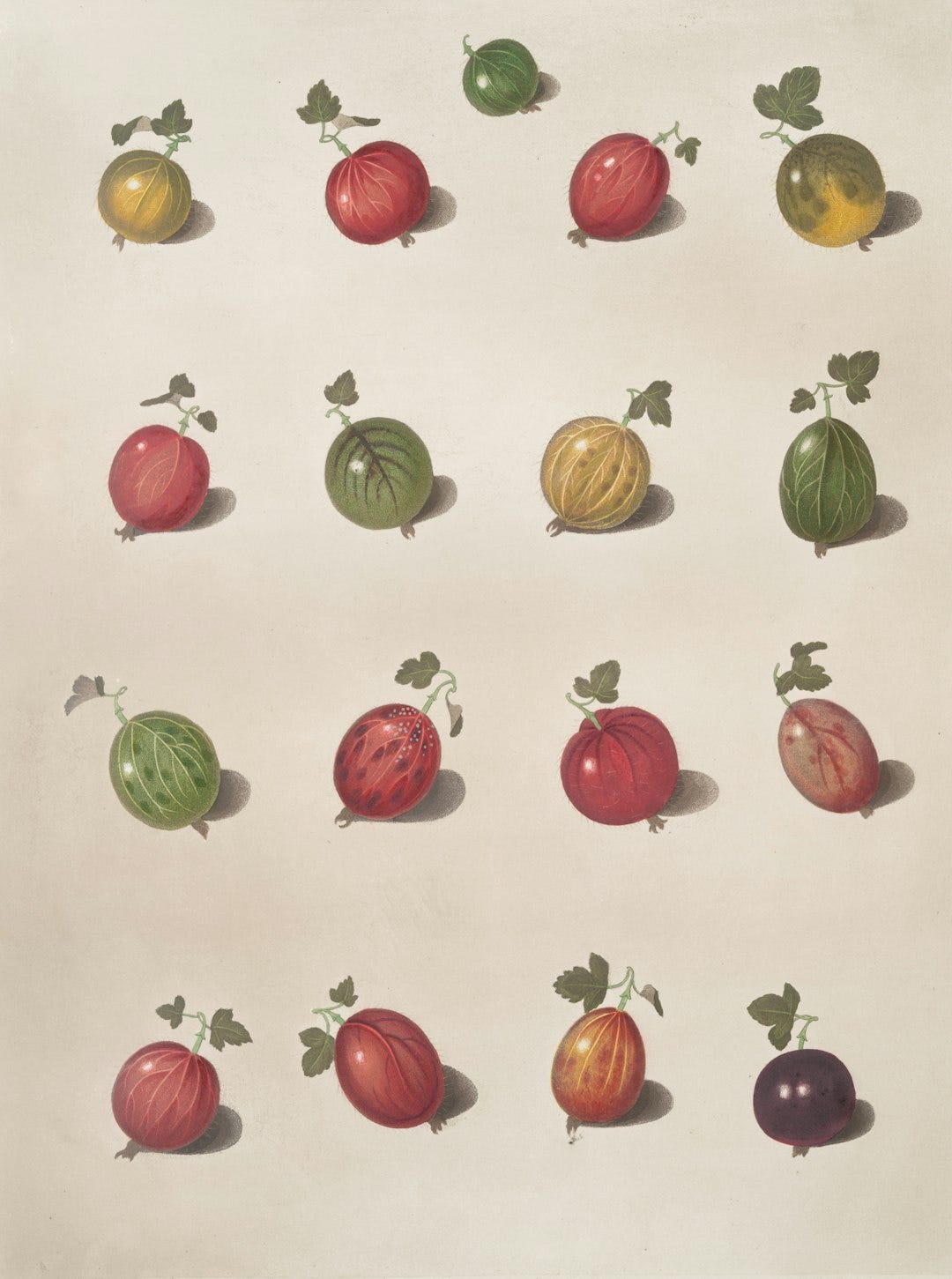

recently and discover that the Italian for gooseberry translates as ‘‘grapes with thorns.’’ How to introduce gooseberries? Many had never seen the berries before. They’d try one if offered, and I’d see their faces pucker if the fruit was less than ripe, offered by a mischievous and unhelpful stall holder who knew what the reaction would be. I’d explain that unripe gooseberries are perfect for cooking; for making sauces, jam, chutney and crumbles. That a gooseberry will ripen perfectly if left in a warm spot, turning from an acid green to a pale mustard seed yellow, their interior shining through the skin. They will be a mellow, sweet, jelly like mouthful, with a flavour like nothing else, tart, aromatic, floral, juicy. A pleasure to eat raw, just as wonderful baked into a pie or tart, to be savoured with thick yellow cream. And if you’re lucky, the gooseberry season will hold a fleeting hand out to the passing elderflower blossom; a marriage of perfect fragrance. If not, elderflower cordial is an acceptable substitute if a less prosaic one.Gooseberries are part of the currant family, ribes. Nothing to do with Chinese gooseberries, or Cape gooseberries. If you’re very lucky, you’ll come across green, red, white and yellow varieties.

Their name derives from the Old Norman/Middle English groses or grosier, the old word for grosielle, the French for redcurrant. In turn, these words come from the Frankish root krûsil which means ‘crisp berry’.

Gooseberries are called ‘le groseillier à maquereau’, in France, ‘mackerel currant’ which is a pleasant reminder that they were often paired with oily fish like mackerel and herrings and fatty meats such as duck. The berries had many colloquial names including; ‘Carberry’, ‘Dayberry’, ‘Dewberry’, ‘Fabes’, ‘Feaps’, ‘Goggle’, ‘Golfob’, ‘Goosegog’, ‘Goosegob’, ‘Groser’, ‘Groset’, ‘Grizzle’ ‘Honey-blob’, ‘Thapes’ and ‘Wineberry’.

They are, as Jane Grigson says, are a northern fruit and ‘condescend to grow, up to the Arctic Circle.’ The flavour is supposed to improve ‘with increased latitude.’

Gooseberries are one of our first summer fruits, vying with strawberries to be the first berries, the first sign that the weather is changing, and other berries are fast on their heels.

The earliest record of their use in Britain dates from a list of trees and shrubs supplied from France to King Edward I in 1275 for planting in the garden at the Tower of London although the OED says that the earliest known use of the noun gooseberry is in the mid 1500s. It was not until the sixteenth century that gooseberry bushes were grown in an increasing number of gardens.

Gooseberry growing declined sharply in the early twentieth century due to the spread of American gooseberry mildew fungus.

Competitive gooseberry growing, and gooseberry shows were once popular all over the North of England, dating from the late 18th century, but declined after the First World War. The number of varieties has also decreased. In 1831 there were 171 berry names listed, mostly unknown today.

Of 171 shows listed in 1845, there are only two of these original societies left in the UK, one in Cheshire and the Egton Bridge Show where official records go back to 1800.

The phrase “to play gooseberry” comes from the time when the fruit was a euphemism for the devil. Old Gooseberry for "the Devil" is recorded from 1796.

Gooseberry as "a chaperon" dates from 1837.

Gooseberries were sometimes known as fayberries, dating from a belief that fairies would shelter from danger in the prickly bushes.

The phrase "gooseberry bush" was a slang term in Britain for pubic hair. It is generally believed that phrase gave rise to the common saying that "Babies were born under a gooseberry bush." Gooseberries (they are hairy) was "testicles," and gooseberry pudding "a woman."

Jane Grigson writes of Edmund Bunyard who in the 1920’s described gooseberries as the fruit ‘par excellence for abundant consumption.’

She says that early gooseberries; the smaller, ‘greener, primitive’ make the best sauce for mackerel and the best pies, jellies and fools.

I top and tail gooseberries with my fingers, pinching off the ends. It’s quicker than a knife or scissors but use whatever is comfortable for you. If I’m pureeing them I don’t bother to top and tail; why would you if they’re going into a sieve?

Got a glut? They make the best chutney, crumble and jam, and a delicious curd.

If you’re making jam, as I did last year, you’ll see that the puree turns a beautiful pink colour.

There is something very satisfying in making use of gooseberries; keeping to a tradition, reviving them and hopefully encouraging more growers to make them more widely available. They freeze beautifully; if I don’t have a glut, I’ll top and tail, start off a bag of them and add as I have more.

All the words, and directions below are from Jane Grigson in Good Things. She’s writing from a time when cream was seen as a luxury ingredient. Measurements are in the old Imperial form.

Jane Grigson’s Gooseberry sauce for Mackerel

She says; make use of the early, small green fruit; the later, mellow gooseberries will not do at all.

Top and tail 1 1b of gooseberries. Cover with cold water and bring gently to a boil. Once a gooseberry taken from the pan will give a little if you squeeze it without collapsing to a mush, drain them well.

Put 2 tablespoons of water and 4oz of sugar into a frying pan and bring to a spanking boil. Turn the gooseberries into the syrup, shaking the pan gently. Pour over your meat or fish as a garnish.

This recipe which depends solely on the sharpness of the gooseberries and the sweetness of the sugar was very popular with Germans in the beginning of the 19th Century.

Gooseberry salad

1 1/2 1b large sweet gooseberries

4 oz sugar

1/2 pint Muscat de Frontignan

Three hours before the meal, top and tail the gooseberries. Put them into a deep bowl with sugar and wine and leave in a cool place (but not the fridge, which is too cold.) Serve in individual glasses.

Gooseberry Fool (for 4-6)

Everybody knows that gooseberry fool, like steak and kidney pudding, or junket is a truly national dish.

Too often gooseberries are over cooked then sieved or liquidised to a smooth slop. Ideally they should be very lightly cooked, then crushed with a fork before being folded into whipped cream. Egg custard is an honourable and ancient alternative to cream. Commercial powder is not. Don’t spoil this springtime luxury. It’s better to halve the quantities than to serve a great floury bowlful.

3/4 lb young gooseberries, topped and tailed

2 oz butter

1/2 pint double cream, whipped

OR

1/4 pint each double and single cream

OR

1/2 pint single cream and 3 egg yolks

Stew the gooseberries slowly in a covered pan with the butter until they are yellow and just cooked. Crush with a fork, sweeten to taste, and mix them carefully and lightly into the whipped cream.

To make the custard, bring single cream to the boil and pour onto the egg yolks, whisking all the time. Set the bowl on top of a pan of hot water and stir steadily until the custard has thickened to double cream consistency. Strain into a bowl and leave to cool before folding through the gooseberries.

Serve in custard glasses or plain white cups, with some homemade almond biscuits or macaroons.

It’s said that the young folk of Northamptonshire ‘after eating as much as they possibly can of this gooseberry fool’ used to frequently roll down a hill and begin eating again. Cream must have been cheaper in those days.

Gooseberry fool can be frozen and served as a cream ice. In this case, sieve the fruit as the pieces of gooseberry would spoil the texture of the ice.

This is lovely and clearly influenced me to buy some gooseberries this morning! By the way, for once the Germans and the Italians take a similar approach: gooseberries are Stachelbeeren in German - thornberries!

Love this