How to stuff a monkey

From Vilnius to Mossel Bay, correctly pronouncing Oranjezicht City Farm Market and making monkey gland steak.

The pages are pale clotted cream yellow. Brittle, flimsy like shards of flaky pastry. They’re held together with strips of sellotape. I hold my breath in case they break away when I touch them.

There is one bookmark; a piece of fine tissue paper. It opens onto a recipe for monkey-gland steak.

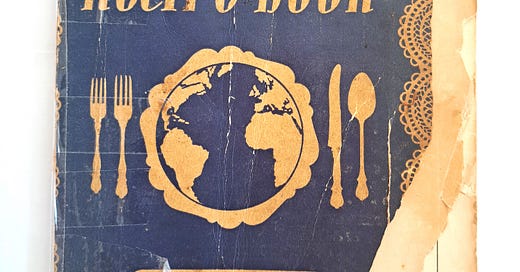

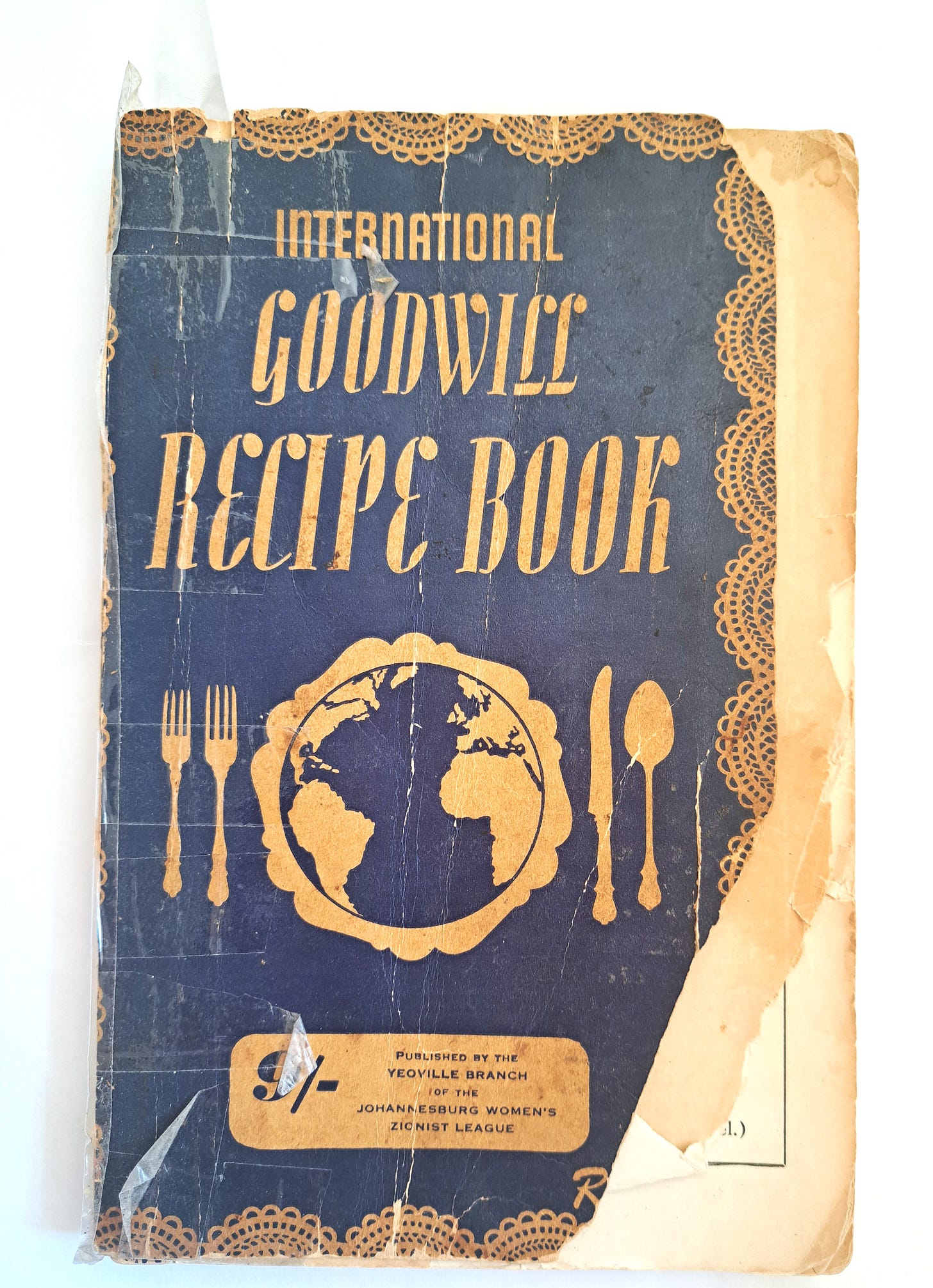

My parents recently moved home. After 60 years in their house, downsizing wasn’t easy. My mums International Goodwill Recipe Book has passed into my hands. I’d forgotton about monkey-gland steak, one of our favourite treat meals. I'd equally forgotton about the old Goodwill cookbook that travelled with mum from South Africa to London.

My parents met in Rhodesia, got married and came to London on their honeymoon.

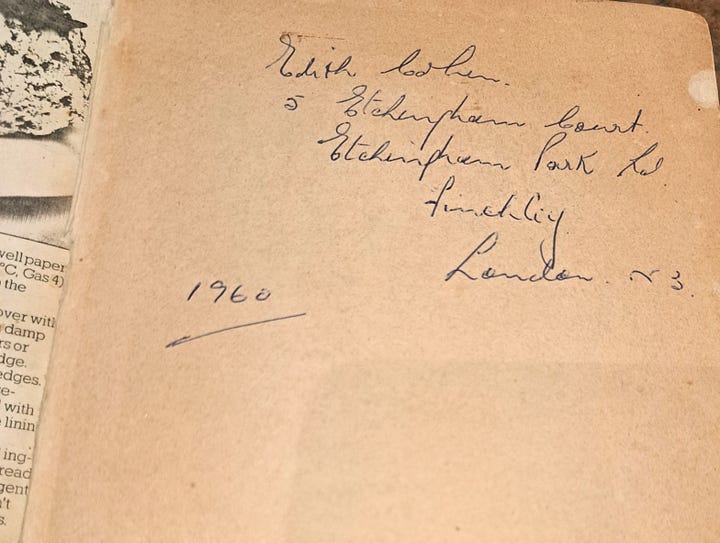

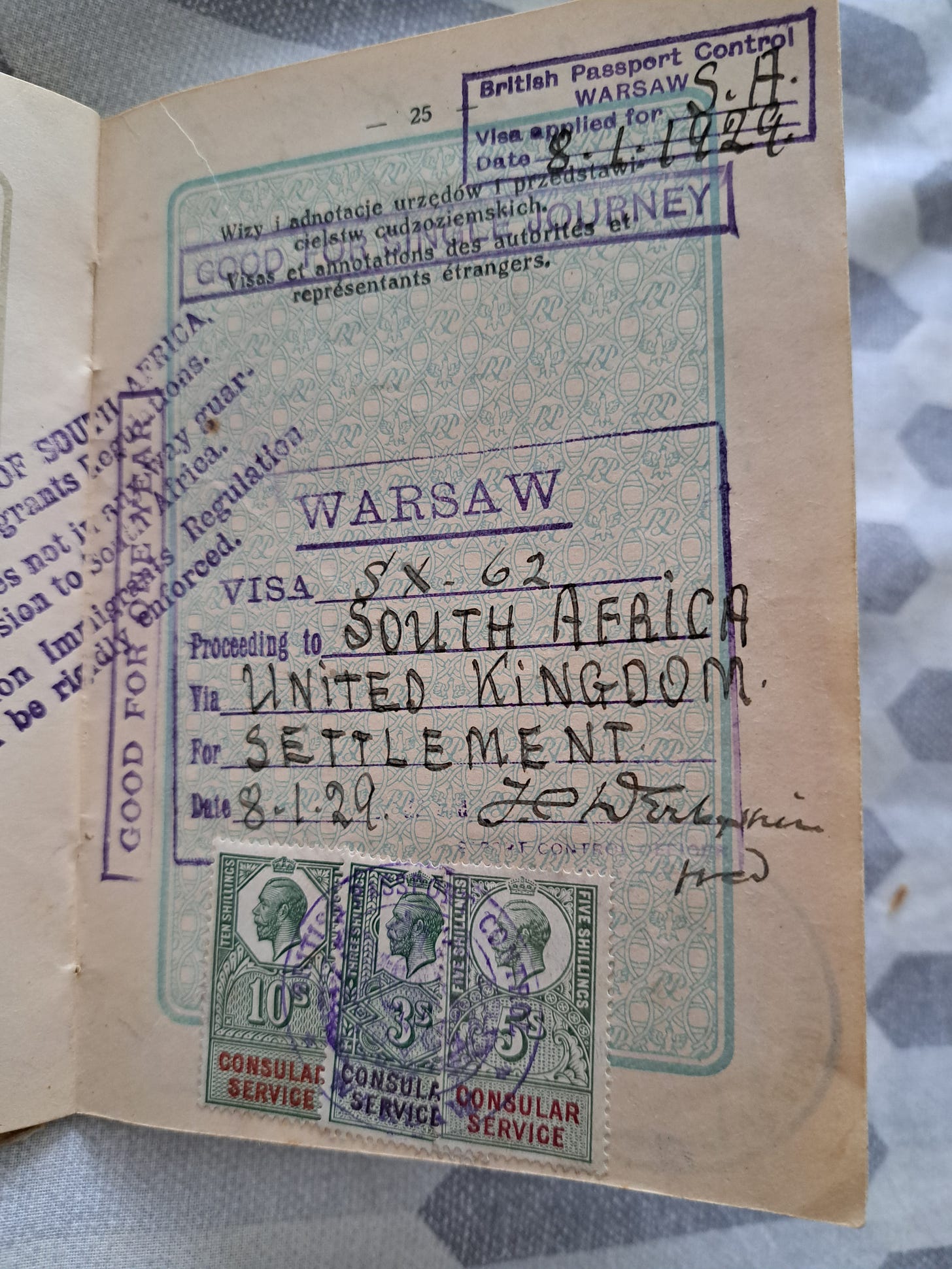

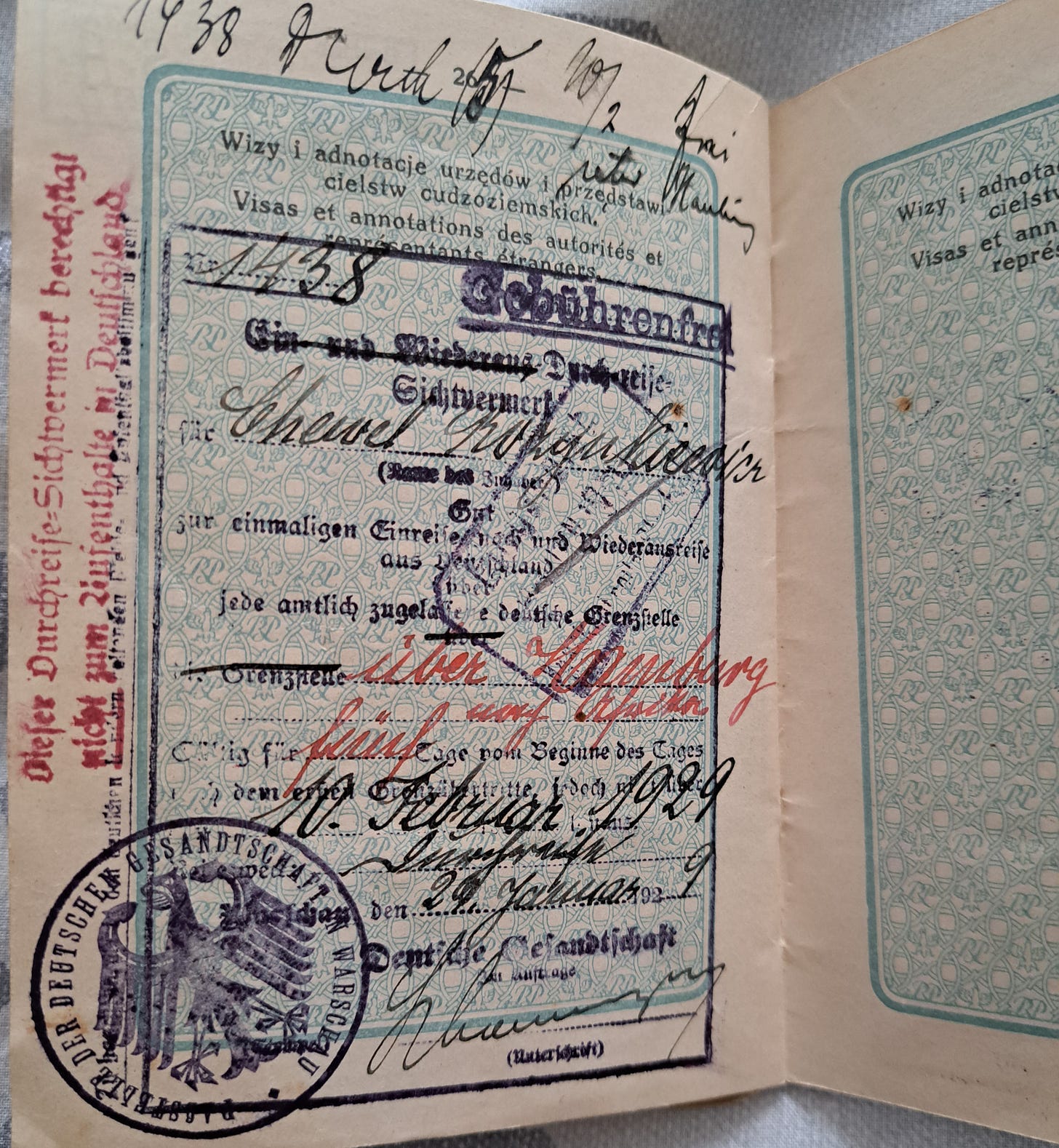

My maternal grandfather left Lithuania in 1929. Between 1924-1929 there was an economic crisis and anti-Jewish policies in Poland. The introduction of strict immigration quotas by the United States and a cousin living in Windoek in Namibia probably helped my grandparents make their decision to start a new life in South Africa1. And just in time; The South African “Quota Act” of 1930 effectively ended immigration from Eastern Europe. If they hadn't emigrated, it's likely I wouldn't be here to write this today. For a long time we wondered why my grandfather had to travel hundreds of miles to Warsaw to get his travel documents stamped. It took time to work out that Vilnius was then part of Poland.

He travelled by ship, a month long journey that took him through the Baltic Sea with the boat hugging the coast of Sweden, past Gothenberg, around the North Danish coast, getting his documents stamped at the ports of Hamburg and Southampton, continuing around the coast of Portugal, Morocco, Ivory Coast, and Gabon, finally arriving in Namibia. My grandmother followed on a later date with her two older children. My mother was born in Windoek in 1932. Her first memory, after they'd moved to Mossel Bay on the Southern Cape was going to school there age 6. Sadly my grandmother died of cancer in 1942. With four children to support, my grandfather couldn't cope. The children were sent to live with cousins in Johannesburg. As there were already five children in the house, this arrangement was short lived. Mum, her sister and younger brother were sent to live at Arcadia orphanage in Johannesburg.

She remembers how self contained Arcadia was, with its own cinema, hospital, and facilities. She has vivid memories of spending 6 weeks in a fever hospital with scarlet fever, then a further 2 weeks in a school hospital.

Their father visited them frequently, bringing goodie bags for his children. My mother asked him for cereal, ofton grape nuts because they were given pap2 for breakfast which she disliked intensely. Sometimes she remembers him bringing them a slab of potato kugal from the boarding house where he lodged. Of course he brought them sweets and chocolates too. He always had sweets in his pockets, a lovely and endearing memory.

When mum left Acadia she found secretarial work in Jo’berg. In 1957, bored with her job and in a rut she and her friend Myra got visas to work in what was then called Salisbury, Rhodesia, now Harare, Zimbabwe. They found accommodation in a boarding house where they didn’t need to cook.

Staying at the same boarding house was a young English man. Mum and dad got to know each other when together with a group of friends, they drove out of the city for a picnic in the countryside, and their car broke down. Dad used one of mums stockings to fix the cars’ fan belt. They got engaged in 1959, the same year her father died.

She was still in mourning when they got married. On honeymoon in London, mum met dads parents for the first time. Her first restaurant experience with them has stayed with her. Not recognising anything on the menu and too embarrassed to ask, she picked skate wing. Difficult to eat, with a challenging texture, she remembers struggling and being embarrassed about coping with all the bones. She’s never eaten it since.

They never returned to South Africa. My aunt Marcia packed up mums belongings for her, which included the Goodwill recipe book.

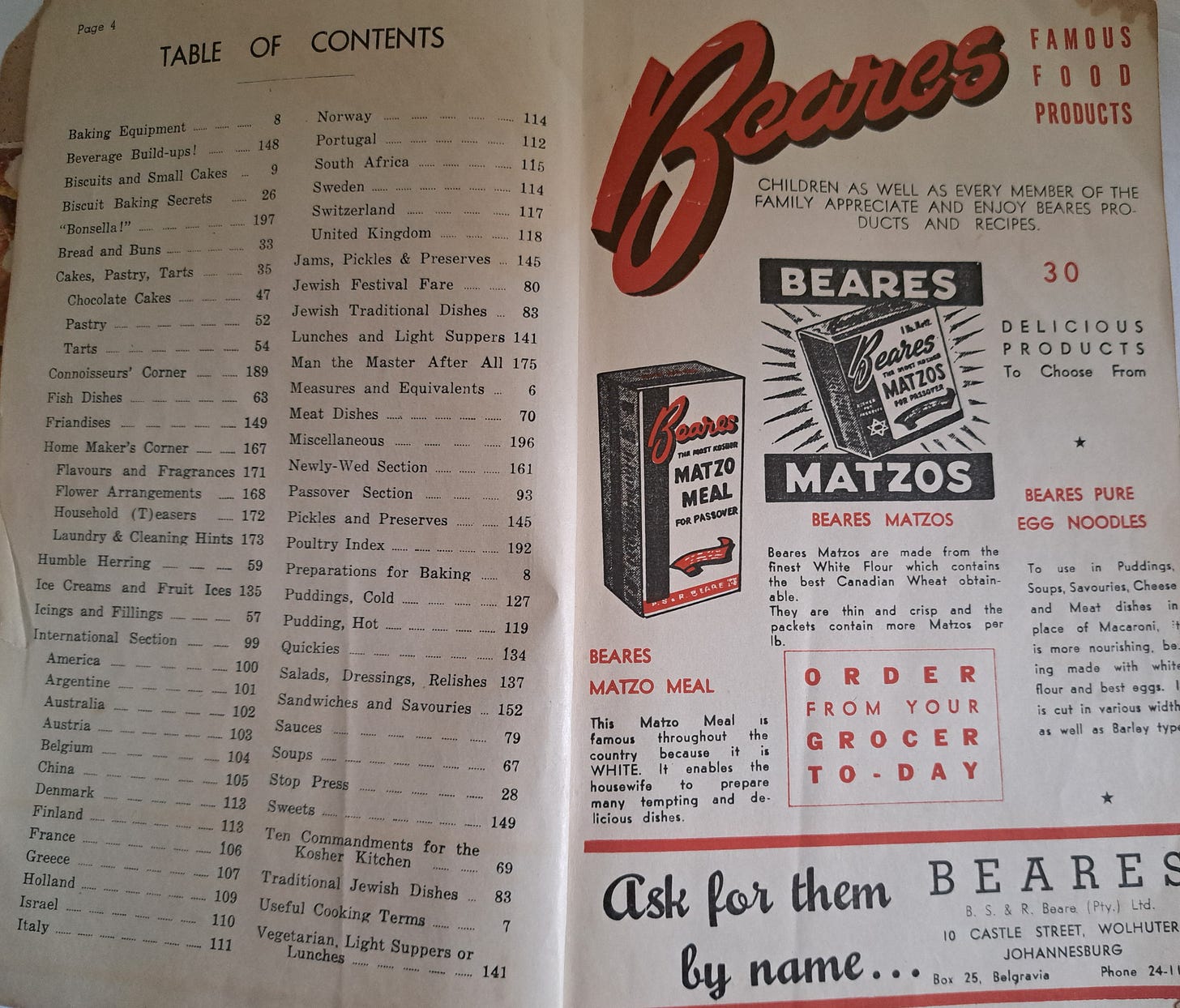

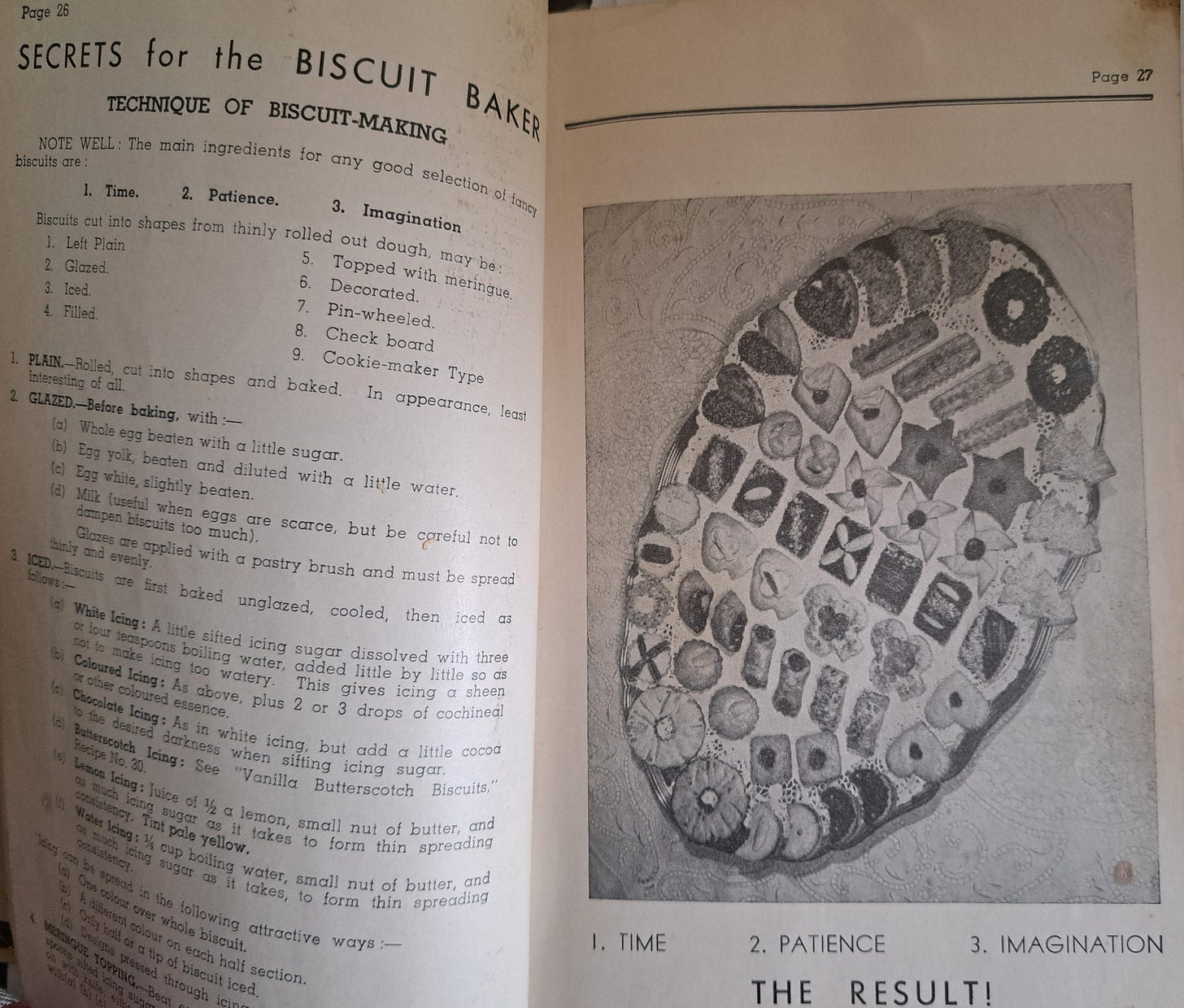

The Goodwill is more a handbook for Jewish women, than a South African cookbook. In its forward it states it contains recipes “just like mother used to make as well as instructions for preparing exotic foods from far off lands”. There are chapters on home making, keeping a kosher kitchen, Passover recipes, and one titled ‘Man the Master after all!’ with recipes contributed by hotel and restaurant chefs in Jo'berg.

We grew up eating the fruits and vegetables mum knew from her homeland; lychees, guavas, ugli fruit and avocados. None of our school friends knew what they were.

A tin of guavas with ice cream was a well loved pudding. I seem to have spent my life on a perfect guava search. Fresh guavas never have the fragrance or slightly granular texture of tinned, even when poached or roasted.

Jocasta Innes in her Paupers cookbook has a recipe for guava fool using as she says, ‘cheap tinned fruit’. Guavas are never cheap, and in the last year they've disappeared altogether from grocery shelves. I have the last tin of guavas in my cupboard.

I've found guava cheese at a Mexican stall in Los Angeles. Frozen guava puree in a Columbian shop in Tottenham. It's tucked away in my freezer, awaiting being turned into a sorbet or ice cream.

I made a pilgrimage to Bakestreet in Hackney when I read on Instagram they were selling strawberry and guava soft serve.

Lychees are equally beloved by us. Around early December we have a yearly conversation; who's spotted the first boxes of lychees at the greengrocers; has the price come down yet? How much is too expensive? Am I mad to consider returning to Cape Town in December to bring back special lychees from Oranjezicht city farm market in Cape Town, the ones with chicken tongue pips

We were there together for the first time a few years ago. Mum, dad, my sister and I. To meet up with our uncle Colin, our Cape Town cousins, and our cousin Lorraine and daughter Courtney who drove from Jo’berg to meet us.

To hear stories about the grandparents we never knew. Piece together complicated family trees, see places through mum's eyes, keeping alive memories that have faded over the past 60 years.

We loved hearing her pronounce Oranjezicht properly, as if she'd never left. Here she is telling me how it's done.

Yiddish was her first language, then Afrikaans, followed by English. She still has a South African accent.

At the market she delightedly recognised dried sour figs, talking about her memories of picking and eating them. Sour figs are a low growing succulent found wild in the Eastern and Western Cape3, with fat waxy leaves, bright purple or yellow flowers in winter and spring and edible sweet & sour tasting fruits that mature in the summer. Eaten fresh as well as dried, they are often made into jam and syrups.

How do we learn to cook? If we're lucky, we watch our parents, usually our mothers. We have a kitchen to practice in. Maybe we're taught at school. Mum had none of these opportunities. It wasn't until recently that I thought to ask her how she learnt, and where. She told me;

‘I learnt after I was married. I didn't need to cook until then. In our first flat, we had friends to stay. I bought a leg of lamb and they showed me what to do with it. I learnt from my mother in law, and my sister, both good cooks'.

The Goodwill recipe book was a gift from mum’s sister. Researching its history, I came across an extraordinary online resource, The South African Jewish Cookbook project. It explains that

“In the mid 20th century, Jewish women across South Africa began to produce cookbooks to raise money for community organisations.

In their cookbooks, South African Jewish women expressed their aspirations, formulated Jewish identity and practices, and carved a place for themselves as women in the community and in their homes. “

My mother's book was published in 1957 in Johannesburg by The Women's Zionist League. The earliest books in the collection were published in the 1940s, in Kimberley and Randfontein. The last book was published by The Jewish Women's Benevolent society in 2010 in Johannesburg.

The books tell stories of the women who wrote them, shining a lens into the history of Jewish immigration to South Africa. The same website says

‘‘The influence of the approximately 40,000 Litvak (Lithuanian Jewish) immigrants to South Africa was so strong that Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow called the South African Jewish community “a colony of Lithuanian Jewry”. The Cookbook Project website emphasises that

‘‘After the Holocaust, South African Jews felt a desire to preserve their connections to their Litvak past. One way to do this was by eating “traditional” food.’’

When Claudia Roden was researching her masterly book of Jewish food, she looked for South African Jewish recipes but found very little that is unique. She talks about South Africans using marie biscuits instead of breadcrumbs or matzo meal and she publishes a recipe for kichelach, a plain oil based biscuit that South African Jews have kept from their Lithuanian homeland.

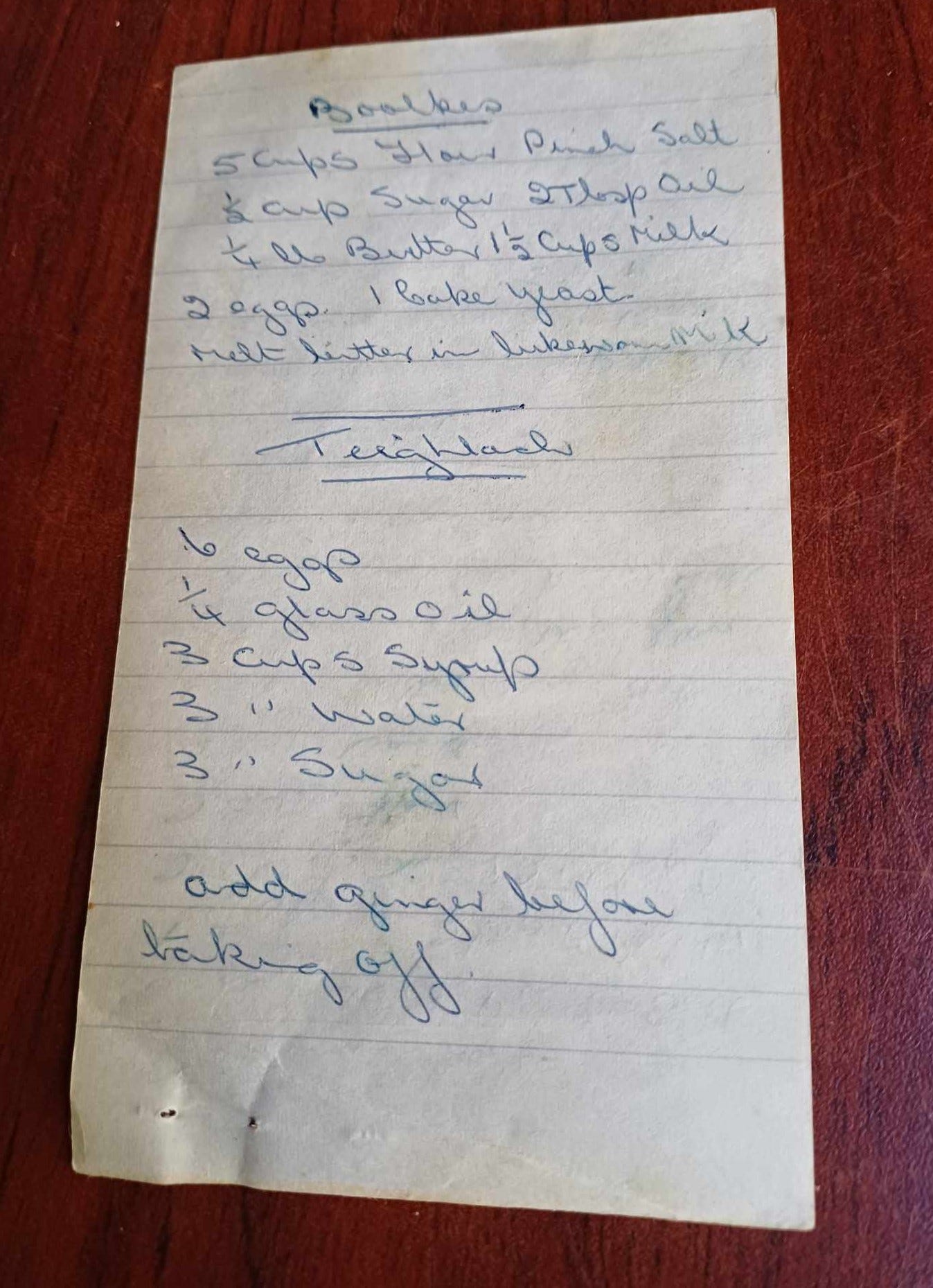

Last year, searching for ghosts of the past in Vilnius, I found a Jewish bakery selling teiglach, pastry buns in a honey syrup. I told mum about the glossy bronze coloured balls on the counter and she visibly brightened, saying how much she misses the teiglach made by her sister.

Claudia Roden says that teiglach is very popular with South African Jews of Lithuanian origin who have kept up the tradition. She adds that many say they don’t often find teiglach and sound very nostalgic.

Sweet and sour dominates the Eastern European Ashkenazi palate. It's common for Sephardi and Israelis to look down their noses at such unsophisticated fare. From sweet chopped herring, to sweet and sour meatballs, red cabbage, stuffed cabbage, sweet and sour pickled cucumbers, sugar on latkes and my mother’s favourite, sugar on an omelette. She says the sweet and sour habit came from her father who no doubt got it from his parents and so on, back into time. The Goodwill book alone has 13 recipes using herring.

Of the South African dishes she cooked, I remember not taking to cold curried pickled fish, very popular in Cape Town. Every deli counter and supermarket has variations.

We knew when mum was about to fry fish because she had special old clothing to wear and the kitchen door would be firmly shut. Then, hours later, we’d go inside to investigate and would find a plate of golden matzo meal covered pieces of fish, cooling on brown paper, and if we were lucky, popovers made with leftover egg and matzo meal. I occasionally make my own fish balls today, with minced fish and onion, an egg, a little matzo meal to bind them, and seasoning including a teaspoon of sugar. Commercial brands are far too sweet. Frying is an occasional treat; the memory lingers on in the kitchen for days afterwards. I’ve tried baking them; they just aren’t the same. A cold fried fish sandwich with chraine, horseradish and beetroot relish on rye bread is one of my favourite things to eat.

Mum loved to eat marie biscuits sandwiched with butter. She still loves biltong, especially if I can find it made from venison. She looks for proper beef boerewors. We brought back mint crisp, a chocolate bar from South Africa, no longer made in the UK and fruit daintees; squares of finely minced dried fruits we remembered from our childhood, and rolls of dried guava paste. A glass piri piri spice bottle with a colourful illustration of a cockerel lived at the back of the spice cupboard. We had no idea what piri piri was; it sounded exotic. And then there was monkey-gland steak.

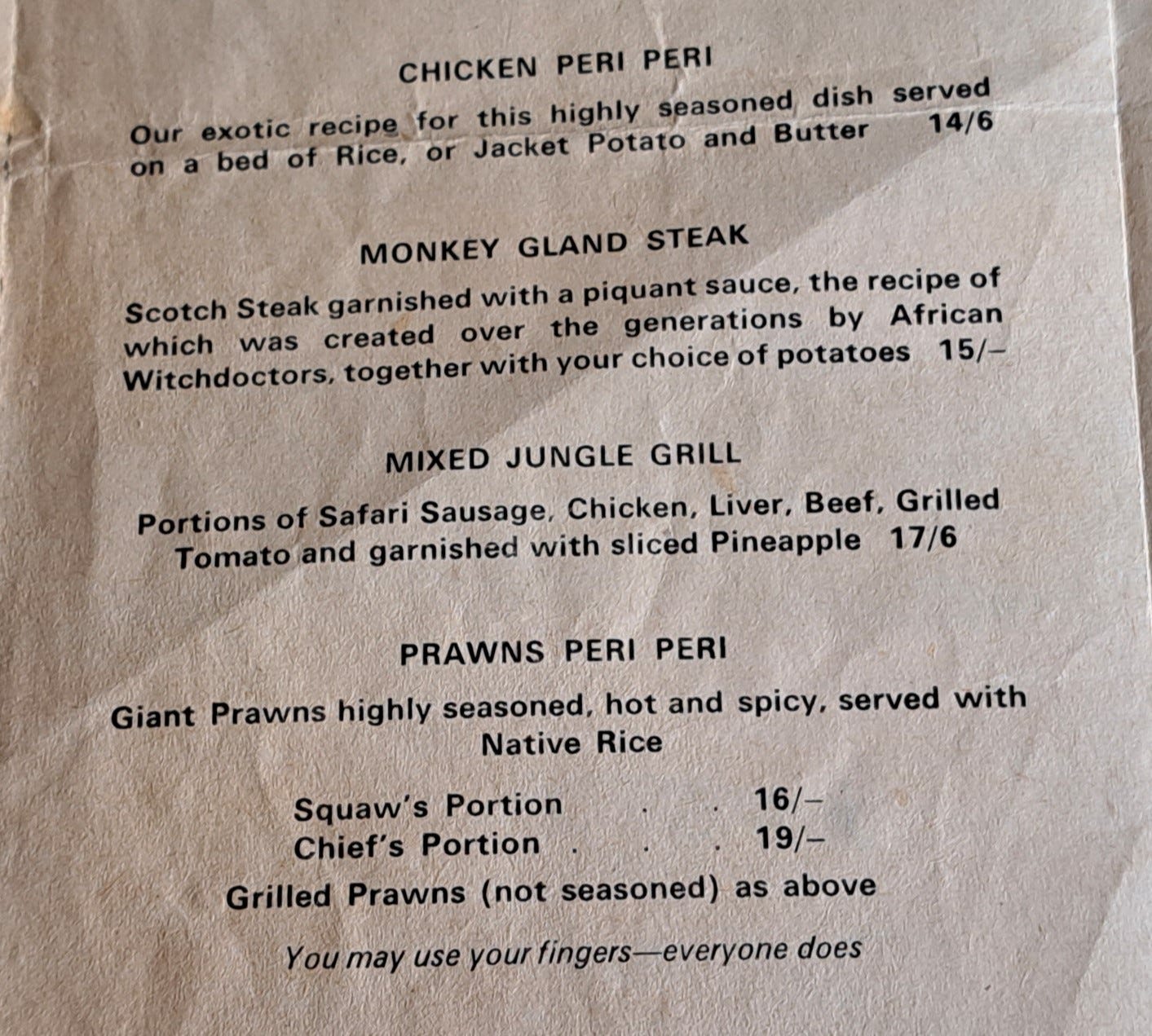

As children, we thought that we were eating a very grown up, sophisticated dish because of the sherry that went into the sauce. When my uncle Colin opened a (it has to be said), pseudo South African restaurant in Earls Court in the 1960’s, Monkey- Gland Steak was on the menu. (So was guava juice; my one memory of the place is being taken downstairs into the kitchen and mum asking if she could help.)

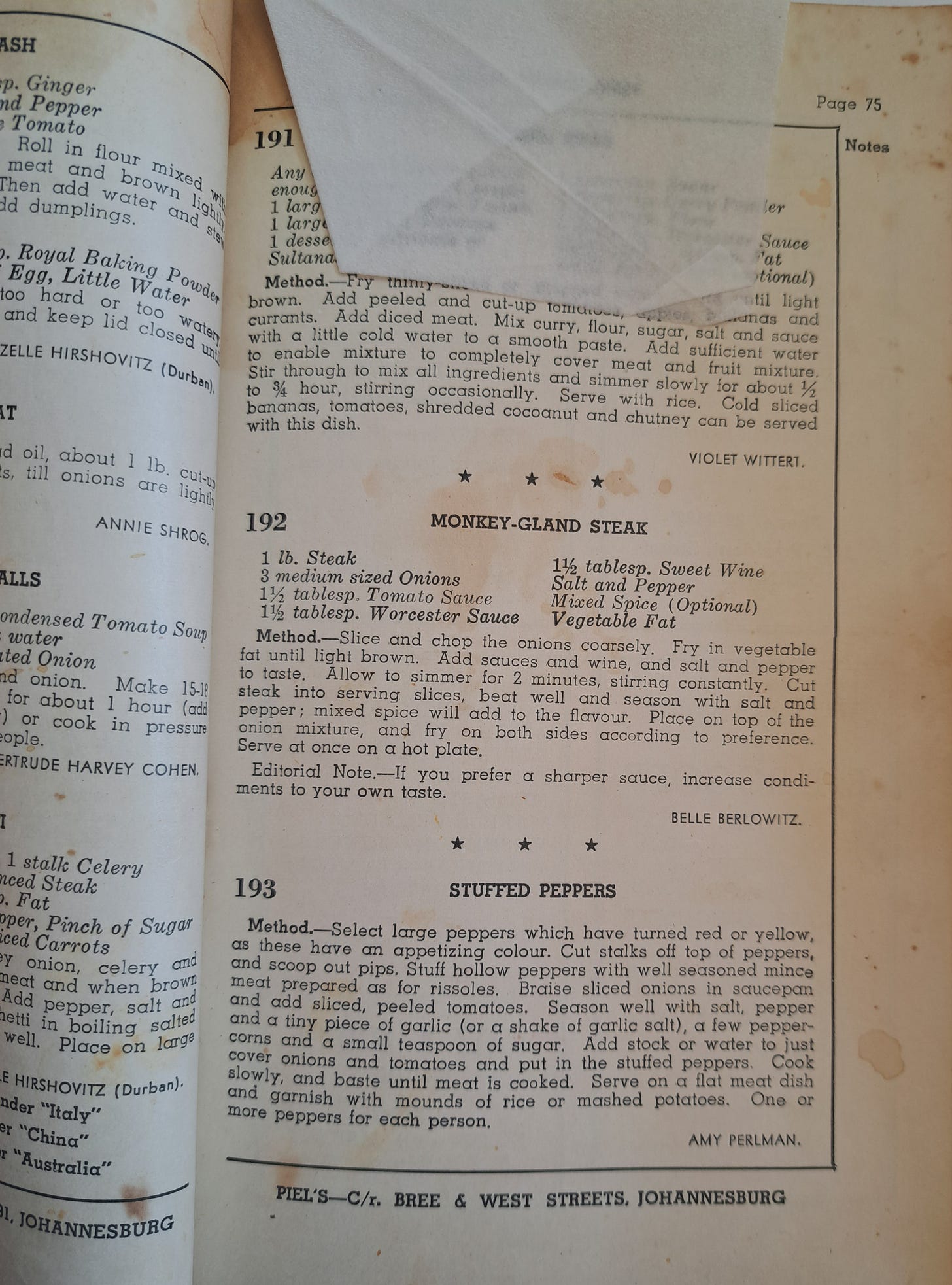

There is no one definitive explanation for the name and many variations on ingredients. Monkey Gland sauce contains ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, sliced onions. The Goodwill recipe uses sweet wine. Mum added sweet sherry. Other recipes balance out the sweet/sour flavour with vinegar and chutney (Mrs Balls obviously).

No monkeys are ever harmed making this dish.

Use a steak hammer or another heavy implement to tenderise pieces of frying steak until they've doubled in size. A large finely sliced onion is sauteed in oil until soft in a frying pan. It was usually at this stage with the kitchen smelling sweetly of onions that we knew what was for supper.

Paper thin slices of mushrooms are tossed into the mix.

Out would come bottles of ketchup and Worcestershire sauce. The bottle of sherry retrieved from the drinks cabinet. No measurements, everything added by eye. A little hot water to slacken the sauce if it’s too thick.

Last of all, the steak. It only needs a few minutes cooking.

A pan on the stove holds a sieve full of cooked rice, steaming dry. Plates are in the oven on a low heat to warm. The sauce is tasted; is it sweet enough, piquant enough? Does it need more hot water to loosen. Serve quickly, on a bed of easy cook rice.

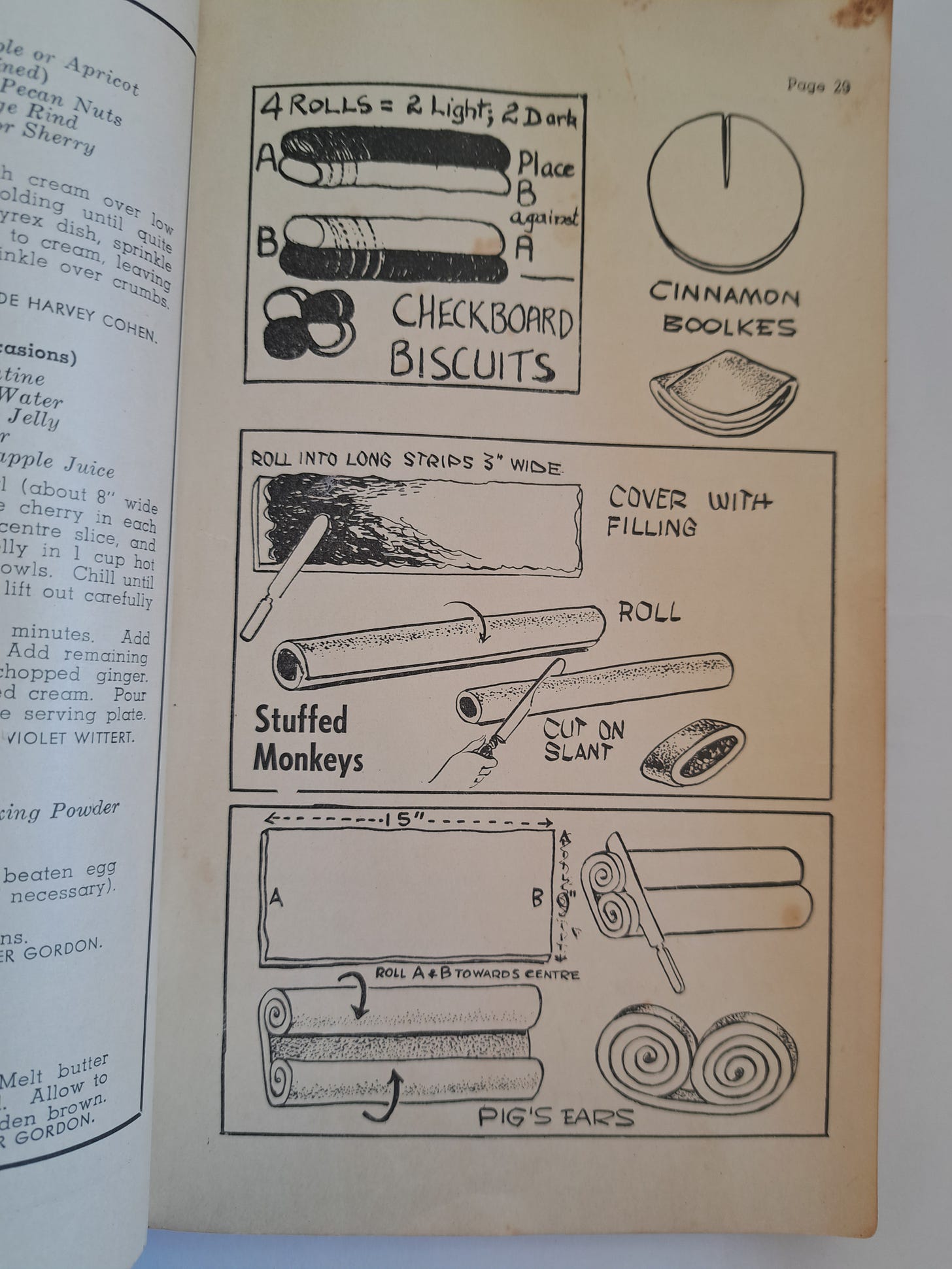

There’s a second recipe in Goodwill Recipe Book that beguiled us as children; Stuffed Monkey, a biscuit rather like a fig roll.

Left alone one afternoon, whilst our mothers were out shopping, my friend Sue and I decided to amuse ourselves by attempting the recipe. What else would we make? Who could resist a biscuit called Stuffed Monkey?

Gil Marks’ Encyclopedia of Jewish Food traces the evolution of the stuffed monkey from bola – a Spanish/Portuguese yeast-raised fruited cake. The recipe made its way to London via the Netherlands, where it changed shape and gained its eponymous ‘stuffing’.

Not impressed with the results of the dough which we found too plain, we decided to increase the recipes’ allure by adding a few drops of green food colouring. Don’t ask me why.

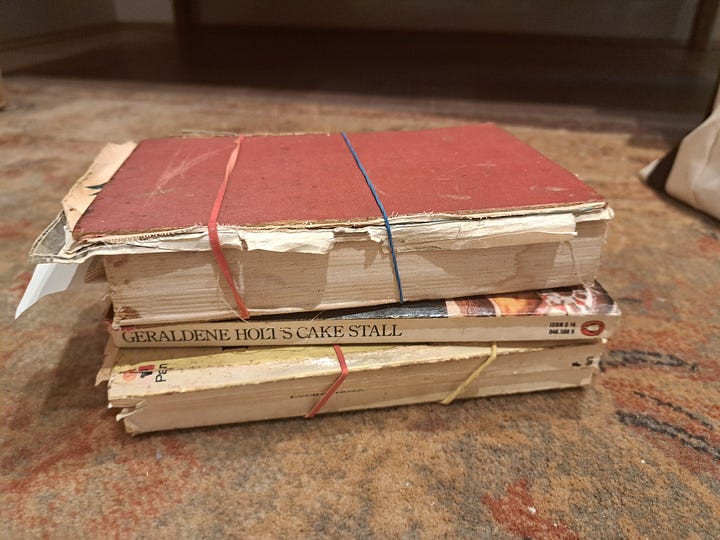

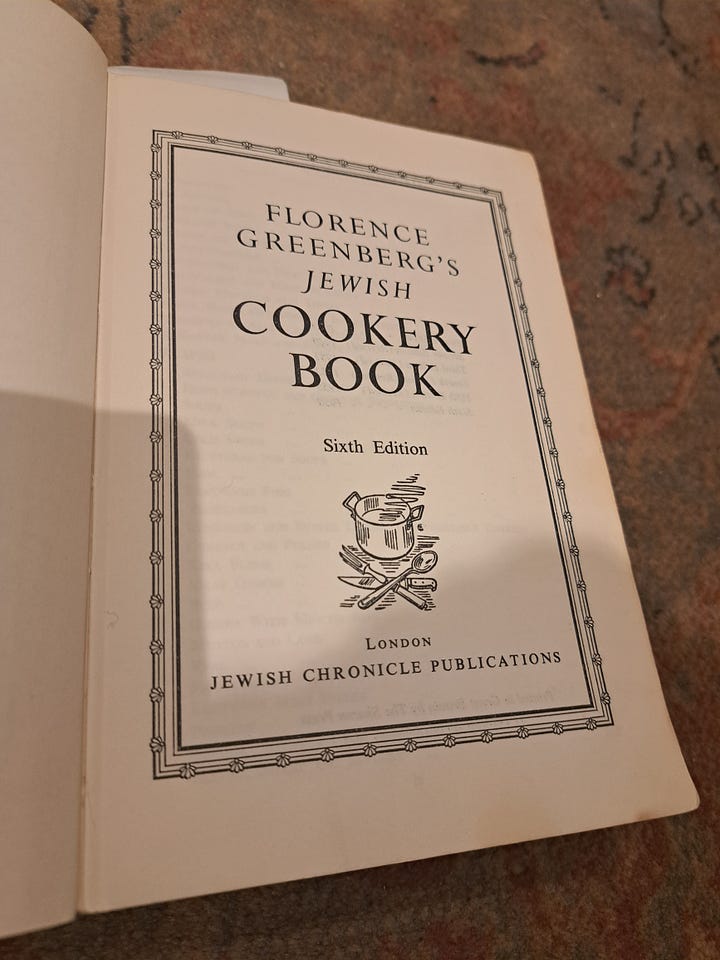

Mum had another helper in the kitchen; Florrie (Florence) Greenberg.

To this day in the kitchen she’ll say, ‘lets see what Florrie says’ when she wants to cook something. Her copy is held together with elastic bands to stop the pages from falling out. I briefly mentioned Florence Greenberg in an earlier post. The Jewish Delia Smith, she wrote the bible for Jewish women in the kitchen, although it’s fair to say that Delia ruled in my mother’s kitchen too.

Florence started writing recipes for The Jewish Chronicle in 1920. Her first book was published in 1934, and she worked as an advisor to the the British Government during the 2nd World War, helping Jewish women with recipes to make the most of rations.

Jewish Cookery was published in 1947, reprinted 13 times between 1947 and 1977. She remained at The Jewish Chronicle until 1962.

In the picture above, and also without a binding due to much use is Evelyn Roses’ The Complete International Jewish Cookbook. She took over from Florence Greenberg at The Jewish Chronicle in 1962, bringing slightly more adventurous recipes to readers, including Sephardi ingredients such as aubergines and chickpeas which never appeared in our house. We could eat what we liked at school, or when eating out, but the food code at home was strict, if not ever kosher. No pork, no shellfish, no hummus. When a next door neighbour gave us a box of frozen prawns in their shells, mum took them out of politeness, handling the box as if it was toxic. On a family holiday in Bournemouth, my father and uncle walked along the prom eating prawns, strewing the ground behind them with the shells, my mother and aunt trailing behind, giving them disapproving looks.

In the 1970’s mum and her friend Irene took an evening class in cordon bleu cookery and for a while there was a stream of adventurous dishes including rainbow fruit tarts and a Danish apple and marzipan pastry. There were always home made cakes and biscuits; she would fill up a huge Tupperware container with different shaped biscuits and we loved searching for our favourite type; stuffed with raisins and almonds, sandwiched with jam, covered with hundreds and thousands or drenched in pastel coloured water icing.

Sunday supper was usually open sandwiches, eaten in front of the television; Stars on Sunday (Harry Secombe singing I’ll walk with God), Going with a Song. Jewish rye bread, topped with egg and onion, chopped herring, chopped liver, rich cream cheese with the obligatory slice of stuffed olive on top, accompanied by lemon tea. Jewish rye bread is a crusty white loaf with caraway seeds. Somewhere along the way from Eastern Europe to England, the rye flour fell away from the bread recipe but that's a path to meander down another day.

Before they moved house, we had a conversation about baked rice, something I’ve written about here. It made her realise she’d not made baked rice with potatoes for a long time, another very particular Jewish dish.

The rules have waned a little over the years. Visiting my parents yesterday, mum told me proudly that dad's been cooking, trying out their new air fryer. Lamb chops for her, pork sausages for him, but cooked separately. Mum wouldn't have the lamb chops cooked below the sausages in case any pork fat dripped on them. “So I got the lamb fat on my sausages” dad said dolefully.

This week we talked about her wanting to make potato kugal. At the age of 92 she told me ‘‘I’ve not made it in a long time. I’ll have to look up the recipe again.’’

Namibia was part of South Africa until gaining independence in 1990

Pap is a traditional porridge made from mielie-meal (ground maize or other grain), and is a staple food across southern Africa (the Afrikaans word pap is taken from Dutch and simply means “porridge” or “gruel”) I love it. Cornmeal porridge is found in different countries around the world.

The genus has become established in many seaside locations wherever there's a mild climate, including Devon, Cornwall, Pembrokeshire and Anglesey.

Wow what a read! So interesting and informative-love all the visuals.

Thank you very much Sarah