If you think that my articles are worth supporting and a monthly or yearly subscription isn't possible;

You can buy me a very reasonably priced cup of coffee.

If reading my work makes you want to bolster my writing and make me feel amazingly appreciated; a monthly or yearly subscription would be fantastic, thank you.

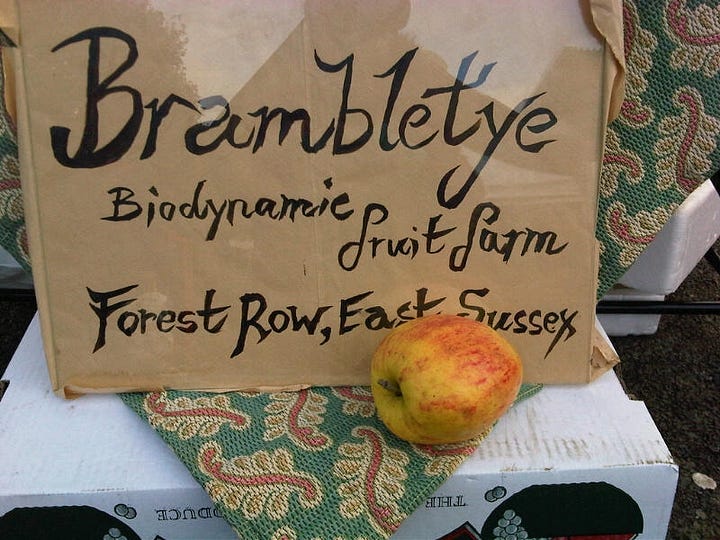

Today we’re meeting Stein Leinders, of Brambletye farm in East Sussex. It’s a biodynamic farm; it’s okay if you don’t know what that is. Many people don’t.

At a farmers market, whenever anyone asked me to explain what biodynamic means the simplest explanation I could give was; it’s organic plus. When I visit Stein and Ellie they tell me that they no longer put up a biodynamic sign on their farmers market stalls.

‘‘People would walk past us, looking for organic produce. They didn’t understand that biodynamic is organic, and much more than that.’’

Before we go any further, a quick dive into the story of Rudolph Steiner, the man behind biodynamic farming.

Born in Croatia in 1861, Steiner studied science and philosophy. He edited Goethe’s scientific works and published his philosophical treatise The Philosophy of Freedom in 1894. His work aimed to create the conditions for a more cohesive and less fragmented society. He developed what he called Anthroposophy, a 'spiritual philosophy' that supported the broadening of personal knowledge, spiritual growth, service and social engagement. Not a religion or a set of beliefs but a practice to develop self knowledge.1

Indications for a healthy farming approach were given by Rudolf Steiner just over a hundred years ago, in 1924 at a time when soil was already showing signs of becoming depleted through the use of artificial fertilisers. Many farmers, gardeners and researchers have since developed these further.2

It begins with the concept that the earth is alive and that each farm or garden can become a self-sustaining and unique organism within it. It promotes a uniquely holistic approach to organic agriculture, gardening, food and health, connecting soil, plants and animals to the universe. This happens through working with lunar phases and the movements of the planets for planting, sowing, tree and vine care, and the use of preparations made from herbal and natural substances for composts, and manure and silica field sprays which are activated and oxygenated by stirring then sprayed at certain times of day.

If you’re still with me, lets meet Stein.

biodynamic farming has such an alternative airy fairy vibe with it and nobody can give a clear answer about it; it's just that it does something amazing.

Stein is eager to show me how the farm has grown. I was last here in 2008 at the time they started selling at our farmers markets in London. We quickly tour the field grown vegetables and poly tunnels planted by Jochem, where chard, young garlic and spring lettuces are starting to fill out, almost ready for market. Over in the orchards, the hens are as feisty as ever I remember, following us around in curious flocks, each group with a cockerel or two strutting around them.

As we gaze on the view on the top of the field Stein notes;

‘‘All of the fields that you can see; They're all biodynamic fields. Brambletye isn’t the only biodynamic farm here. Forest Row is famous for it.

“Tablehurst is still here. Plawhatch is up the road. There's Michael Hall. Emerson College. So there's something about this area. It's amazing. That draws you in.’’

Bramblteye Farm nestles into the rolling hills of the High Wealds in an area that magically seems to attract like minded people and businesses. In the same area in and around Forest Row there’s the Steiner School (Michael Hall), as well as the farms Stein mentions, and Emerson College, founded on the principles of Rudolph Steiner.

It’s sad to hear that Stein and Ellie don’t advertise themselves as biodynamic anymore, as Stein explains;

‘‘I had customers in London walk up to the stall and they asked what is biodynamic and I explained and they told me I'm lying. I had a really long think about it; if they don't want to hear it I don't need to tell them so we got all of our wooden signs out we painted them just with organic, not biodynamic and we saw an uplift of 25% in sales. The problem is is that biodynamic farming has such an alternative airy fairy vibe with it and nobody can give a clear answer about it it's just that it does something amazing.

“Most people don't understand; the easiest way to explain it is that you use a different phase of the moon for planting and harvesting. But there's an enormous amount more and unfortunately, I can't educate them’’

What made you choose biodynamic when you were training?

‘‘Secretly it was or is continuously producing the best flavoured produce not always the best-looking produce; producing the real product. That really is what I enjoy. That's hand-in-hand with the challenge of producing and growing that product. That's our master plan.

“I am as much an apple grower as my conventional colleagues it's just for the last 20 years I wasn't accepted because I was a young foreign grower, growing in a method that nobody understood but 25 years later we're still growing.

“I'm still unclear why our fruit tastes the way it does. Because there's a clear distinction between stuff that we grow on this side and stuff that my colleagues grow.’’

Stein trained in biodynamic farming at Warmonderhof college in Holland. After renting a field at nearby Tablehurst biodynamic farm he managed to buy his own fields, and Brambltye was born. Originally Stein planted 35,000 trees, today he has around 40,000 fruit trees.

‘‘It's famous, horrible Sussex clay here. It's useless other than to grow trees.‘‘

Some of the varieties you may not have heard of; he buys his organic trees from The Netherlands.

Is it difficult sourcing organic varieties of the fruit trees?

‘‘I don't think I can actually buy commercially reared trees or raised trees, grown trees, in this country in the number that we need, but also with all the plant certificates that they're virus-free and that they are grown organically.’’

What's the difference between buying an organic three-year-old and a conventionally grown tree?

‘‘Price.’’

What else makes it organic?

‘‘Not having been sprayed with the conventional chemicals that control pests and disease. It is also how the tree is fed. So you end up with a tree that grows a little bit slower.’’

‘‘When you look at the tree, you can't tell the difference. It's really hard to tell the difference unless you start growing those same varieties side by side, organic and non-organic. Then you can tell.

Are you finding it's easier to find them in the Netherlands?

‘‘I can't get them in the UK. I can go to the nursery in Holland and I will be able to get four or five acres worth of trees and they’re uniform. It's not grown on that scale in this country.

‘‘I'm no different to a conventional grower. It's just what you do and how you do it. The problems are the same. It's just that in the organic system, we have to be way more creative to find a solution. I was speaking to my agronomist this morning and I was asking if he had found any woolly aphids. I don't have them. I want them because that way I can maintain my natural predators.’’

How do you treat aphids?

‘‘I don’t. Natural predators clean them up.’’

Do you introduce or encourage them?

‘‘I encourage them. There’s one. A rosy apple aphid, all alone, and I’m not worried about this.’’

Everyone always says, oh, your orchard is messy. And actually, it's a controlled messy.

We’re walking through orchards, looking at the mini flower meadows; patches of flowers and long grasses between each tree.

‘‘We are very much encouraged to let all of what grows in the orchard, flower. The dandelions have flowered and gone to seed, now we're cutting and then the next lot of flowers are going to come through. Also under the trees, I am not allowed to keep it bare all season long. So early spring we cultivate, then now after flowering, we will cultivate again. And then after that, we will let the grass and the weeds come back.

‘‘Normally when it's a nice dewy morning, you can walk through the orchard and there's toads and there's baby frogs. And then later in the day when it's nice and warm, you find snakes. Everyone always says, oh, your orchard is messy. And actually, it's a controlled messy.

“I like my strips that are full of hiding places. I like weeds that come through on the side of the tree. My son hates it because he can't control it because that's his job. But at the same time, it's where the toads hide, it's where the frogs hide.

“I go to an organic orchard now where we do the pollination and they're throwing everything at it to keep it completely sterile. So there are differences; we are doing exactly the same, but our answers to the problem that is at hand, it's just different.’’

Would you say you have a more holistic approach?

‘‘Almost. A more pragmatic approach.’’

Pragmatic, holistic?

‘‘Yes. It's okay that other species grow there. As long as it doesn't interfere with the fruit ripening and growing, it's okay.

“You also have to be sensitive to the needs of the chickens because they continuously need fresh grazing. If I end up with a meadow where it's four foot tall, they will just lay eggs outside and then we don't have eggs. And we can't have eggs outside because we will very soon have no egg business.’’

Currently UK supermarkets are basically not stocking organic apples grown in this country because they don't want the bad publicity of underpaying growers. And the imports are so much cheaper.

Stein would like to plant more trees, expand the farm.

‘‘Everything is full so unless we take on new sites we can't plant. but we also know that we have to plant more. My son always wants to plant blackcurrants, gooseberries and redcurrants to pick with the harvester, to process, to make our beautiful syrups. And then we also need to plant more Natyra because that's an apple that just we never have enough of.

‘‘We need to plant more pears because we don't grow enough of those. So yes, we need to find a new site.

Can you afford to plant more?

‘‘We can't afford to do any more. It's a balance; that's the problem. We need to sit down and look at how can we improve on what we're doing and it's like yes, we walked away from the supermarket but quite possibly we need to turn around, go full circle; and we need to go there to be able to bring a new assortment of new varieties that are capable of being grown organically. And that are so far out of the reach of a comfort zone that we're seeing in a conventional market that it's like yes, it's an apple but it's so different. Currently UK supermarkets are basically not stocking organic apples grown in this country because they don't want the bad publicity of underpaying growers. 3 And the imports are so much cheaper.

I don't mind being left with a zero figure if there was a 10% profit margin; the problem is that it's not there

‘‘The prices don't match up with the cost of production. ‘We're not stocking your apples so we're not underpaying you’, that's the right publicity. That's not what they're saying but that's what's happening. And it's a problem.

‘‘The cost of establishing an orchard is now so high with the prices that we’re being paid, we don't get a return. The costs are too high to plant and the money that we're getting for apples is too low. ‘‘

What do you blame these rising costs on?

‘‘I don't know. Everyone wanting more money? And the consumer not willing to pay more? This is really scary. it's tough.

‘‘It's a very delicate balance between how much can I charge and how much can I sell; how much do I have to sell and how much are they not willing to prepare to pay.’’

Biodynamic is often more expensive than organic; why is that? What do you tell people?

‘‘that it is more work and that my production is lower and I have to meet in the middle but at the same time it's like all of the orchards when they come into full production, I can't necessarily say, it's like if I need to sell a portion for £4.50 and the price is currently £3.20 for a portion, I might be able to go to £3.40 but if I push up to £4.00, it might be that I only sell half, and if I only sell half then maybe selling less at a lower price is better because we're still clearing the crop.

‘‘What is way worse for me as a grower is that if I don't clear the crop and it is exactly that balance; currently the cost of planting one hectare ( 2.4 acres) is £45,000 and I can't recoup that, it's just the cost of money is extremely high because of interest rates and then also that £45,000 you have to take out so that in 10 years time you can use that again to plant again and both are too much, never mind a piece of land to go and plant it on, it's like it's so out of balance currently.’’

Do you try to aim for a certain percentage of profit margin?

‘‘I definitely aim for 10% but we're reaching between 1% and and 2% I think for the last two years it was 1.2%.’’

Does that keep you?

‘‘It's great because I'm not going backwards; my staff are being paid, things are being paid but at that level of profit we're not getting the money we need to make investments and that is the problem. I don't mind being left with a zero figure if there was a 10% profit margin; the problem is that it's not there.

‘‘My son Joris wants to plant more orchards, but there's no money to do it because it doesn't add up. And I think it will correct itself, but it will take some time.’’

Why did you walk away from supermarkets?

‘‘When I started there were very few organic growers, or very little organic production and then more organic growers joined or more conventional growers converted to organic which meant that we were getting more organic fruit availability.

‘‘What happens in a crowded market is, they get the pick of the best and they start dictating what they can and can't take and want and I decided that I don't want to be part of that race.

‘‘I started working with box schemes, we started at farmers markets but because we were used to catering for big customers I would come to market with two or three varieties of apple and it's very difficult to cater to the people that come to markets asking, do you want a sweet apple, do you want a sharp apple I don't know I want a crispy sweet apple it's like I've got sweet well I've got crispy and sharp; not every apple stores the same, not every apple eats the same; a Jonagold is sweet but also it doesn't appear crispy because of its texture.’’

I hate going to London, I detest it. I love talking to people, but I’d much rather be out here. But, without going to market I can’t do this!

What does selling at farmers markets mean to you

‘‘It means I’m in control of what I sell. So if I have a beautiful crop, I can still take out 10% and sell the most glorious product we’ve ever grown, and then if there’s a new variety of apple that has all sorts of issues and is ugly but tastes amazing, I can still pack and sell it, I can explain to people what happened, how I got it wrong and they still appreciate the most amazing flavours, and then they can see progression over the years, where we’re getting to grips with new varieties, and how to grow it, pick and store it. It’s like they are sharing & appreciating my failures. Taking this wholesome product, putting it out there, every week, it’s amazing. That’s what it means.

‘‘In the same breath, I hate going to London, I detest it. I love talking to people, but I’d much rather be out here. But, without going to market I can’t do this! We went down the supermarket route before, it worked, we built our business, but it was a very lone existence. It’s like 80% of the year I was out on my own, now I’m never alone. so it’s great.’’

When you started farmers markets, do you remember how many lines you came with?

‘‘I think we had three types of apple, apple juice and eggs and we had some honey for a few weeks and then that was it. I think we now grow over 20 maybe 25 different varieties of apple I think we've got six varieties of pear, maybe seven, we've got some cherries, we've got some plums, lots of honey, lots of ferments, juices, eggs; I think we grow 20 different types of veg although all seasonal; there's so many things.’’

A lot more than when you started

‘‘Yes; the only way to change is for customers to understand how their food is being produced, to see it and taste it. supermarkets aren’t interested. So how else are you going to reach a large number of customers than through what we’re doing; this has been 25 years in the making. and it’s only just getting to a point where the volumes are becoming serious.’’

We’re walking among trees loaded down with generous fruitlets of future apples and pears. Apart from our voices, the layers of sounds filling the landscape like a musical score are bees loudly working, chickens and cockerels running around between the trees, fussily searching for juicy grubs to eat. Overhead, a chorus of birds singing. In the distance, sounds of farm machinery.

I’m introduced to apple and pear varieties from The Netherlands, some I’ve tried before, others that are new to me including Early Desire and Xenia.

and Stein says;

‘‘Each variety you have to learn, and each variety that you plant it's just a gamble.’’

Under some trees there are blocks of white substrate used as mulch, that comes from the farms mushroom production.

‘‘Mushrooms are our biggest line’’ Stein proudly states. ‘‘It isn't weather dependent because we regulate the climate.’’

On my first visit back in 2008, mushrooms were an experiment, grown in a modest blacked out tunnel, hanging down from grow bags. They’ve since expanded hugely.

Stein shows me around the mushroom unit where a team of people are busy picking, packing and opening new blocks ready to grow;

‘‘The blocks are made of wood. The white stuff is the fungus, the mycelium. And then we're creating the right conditions in the room for them to start pinning. first you get tiny pins that look like mushrooms, it takes ten days for them to grow out into harvestable mushrooms. It's beautiful. We've got one room for king. One room here for maitake, Another room over there for shiitake, one room where we grow the shimichi.

‘‘We’ve got the container outside where we grow the grey oyster. To make the volume that we do, we need a shed four times larger than we have currently.’’

Freshly picked large oyster mushrooms are in containers, too big for farmers markets; these are destined for the kitchens at one of Ottolenghis’ restaurants.

Do the mushrooms help you through the hungry gap?

‘‘Yes completely. every product that is at the table every week makes it possible to sell our seasonal produce; it is incredibly difficult to come to market.

‘‘I remember the early years that we went to farmers market and we got to April; ‘now we're done thank you, see you in a few months time.’ There's no point in coming but then customers forget about you and it just doesn't work; unless you're in with them every week it's extremely difficult to actually just sell the product when it is there.’’

How's the hungry gap been this year for you?

‘‘I think we've got another few weeks of apples left; vegetables have dropped off at Christmas already, really that is the one thing that's really difficult once the certain bits of the vegetables go that's the end of it and then you know I come to market with just onions and a couple of leeks and it's not moving, people are not picking it up they're not seeing it, it's lost on the table.’’

We’ve moved on to look at the nursery where queen bees are being raised.

‘‘this corner of chaos is where I rear the queens; six hives, one swarm and a cell builder; this is the queen nursery, let's see how brave we are; so there's a little bit of food and then we introduce a young queen and they will take her out on a mating flight and then they're building the comb inside she'll start laying and then when we find that she's laying we introduce her to a new big colony.

‘‘We've got 250 production colonies and we need to increase that to 350 to have enough colonies to do all of the pollination across the orchard that we pollinate.’’

We’ve stopped to talk to two farm workers who’ve just collected eggs from one of the mobile hen houses, joyful because there are pullet eggs again.

‘‘We’re going to be bringing whole frames of honey; there is cut comb at market, but it’s not celebrated enough.’’

Our last stop, rows of an apple called Evita where Stein points out a disease, tree canker;

‘‘you can just about see it here, it’s a fungus. It goes all the way around, kills the cambiun, that’s it.’’ He points out Nora, busy pruning in the distance.

‘‘That’s what Nora’s doing, she’ll cut it there and then it will grow a new top. These went in last year and they’re already covered in fruit, looking very hopeful.’’

Last words from Stein; with loud background competition.

More about the orchard eggs next week.

You can find Brambletye at various farmers markets in London. They now sell year round. Currently they’re bringing spring honey, lettuce, chard, parsley, wet garlic and mushrooms to market.

If you’re able to, please click on the ♥ to like this post to help visibility on Substack; more people get to read and share it.

It’s sometimes difficult to find UK grown apples in supermarkets let alone organic. This is a typical label from information provided by Ocado on their organic apples; Country of origin may vary between Argentina, Chile, France, Italy, New Zealand, South Africa, UK and USA.

“it’s okay if you don’t know what that is.” I’m so glad you started with this, as I thought I was acting dense 😅 A fantastic piece, Cheryl - such an enjoyable read and great to learn more about the work they’re doing.

Oh I wish I lived closer to London. They sound amazing.