Welcome to the latest installment from me, Queen of Markets. This week, I’m getting up extremely early in the morning, just for you.

Please can you take a second to click on the ❤ button to like this post, or share and restack. It really does help my work become more wider known about on Substack.

I appreciate everyone of you who's subscribed. If you're able to become a paid subscriber I would be overjoyed. It takes time and commitment to research and write these posts every week.

There's another way to support me if you think that my work is worth paying for and a monthly or yearly subscription isn't possible;

Whatever your reason for being here, and I hope it’s because you DO love my writing, I’m so glad you’ve joined me.

Your idea of Covent Garden fruit and vegetable market might be based upon My Fair Lady. If you’re like me, maybe you remember the market scene in The Red Shoes, or pictures from the original site before the chain stores and restaurants moved in.

At 4.30am on a cold winter’s morning, the vast warehouses loom like grey monoliths over Nine Elms and Battersea Power station. The market isn’t under one roof, it’s an enclave, an empire, the largest wholesale market in the UK. The charm of Covent Garden was replaced by practicality. Trucks are loading up their deliveries and trade is starting to slow down. The market has been busy since the previous night.

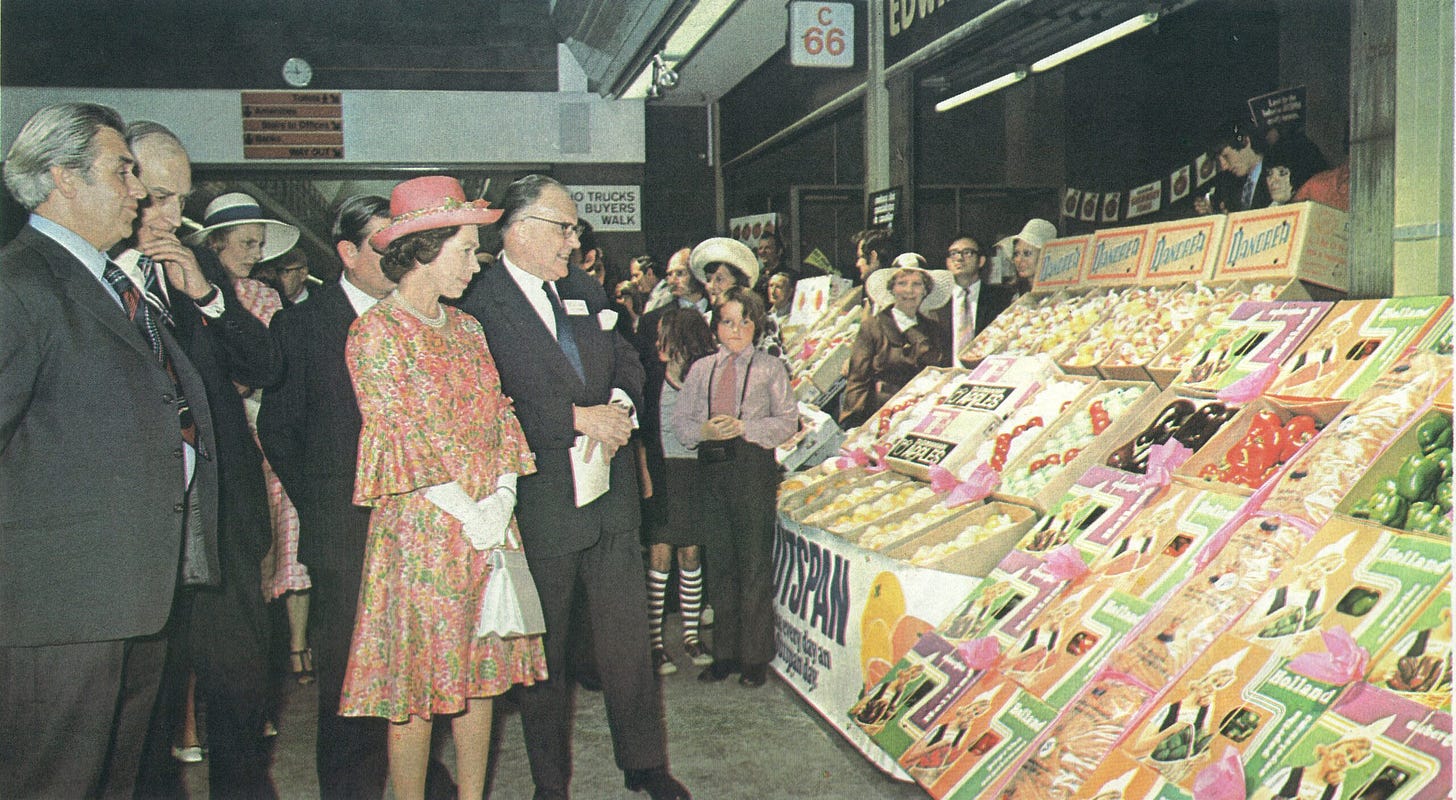

The market has a history stretching back more than 800 years and this year, it’s celebrating 50 years at its Nine Elms location since moving from the old Covent Garden site the market inhabited for more than 300 years.

Around 200 tenants of all shapes and sizes are based here, employing over 2,500 people, with a combined turnover of £880 million in the last financial year. This is the base for the UKs best and most experienced multi-generational fresh produce businesses – fruit, vegetables, flowers and fine food.

As well as the market, it’s home to the Food Exchange, a mix of entrepreneurial food businesses, and Mission Kitchen, whose start-up members share commercial kitchen and co-working spaces.

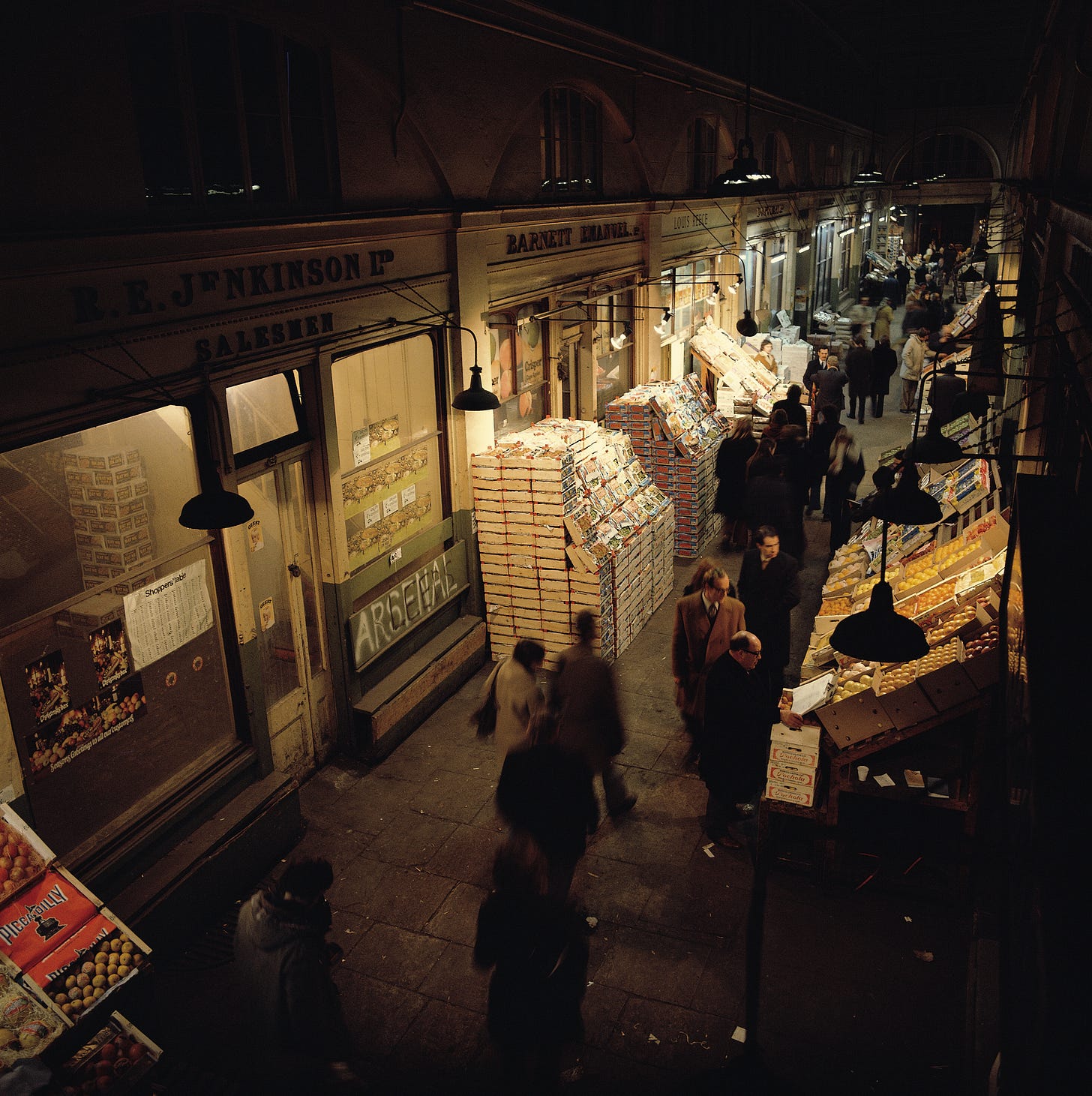

I’m just about old enough to remember the market when it was at Covent Garden. In my mind I have a picture of us as a family walking through the stalls as they packed up, remembering the hand knitted blue cardigan I was wearing, my patent leather shoes weaving in between crates and pieces of fruit and cabbage leaves that had fallen into gutters, having my photo taken with a pearly king. The market moved in 1974, and not before time according to some of the traders at New Covent Garden who still remember it.

Before we get to 1974, are you ready for a whirlwind history lesson?

The first known reference to the market occurs in 1654. In 1670 the Earl of Bedford obtained charter rights to run the market. He and his heirs were authorized to hold a market in the Piazza on every day in the year except Sundays and Christmas Day ‘for the buying and selling of all manner of fruit, flowers, roots and herbs.’

By 1748 the vestry of St. Paul's presented to the 4th Duke a memorial signed by sixty-two inhabitants complaining of 'the Nusances ' and ‘The 'stench and filth of the Markett,’

In the latter part of the eighteenth century Covent Garden had become 'the greatest market in England for herbs, fruit and flowers'. It was divided by customary usage into different sectors, the herb shops and better-class fruiterers in the south row and the florists on the west side. The north side was devoted to roots and kitchen garden produce (except potatoes, which were on the south side), the east to peas and beans or cherries and strawberries according to the season, while in the centre were the 'bird-sellers, dealers in old iron, and large displays of crockery-ware'. 1

By the early nineteenth century Covent Garden was already the focal point of a highly diverse trade. Within ten miles of London there were 15,000 acres of market garden ground, in which up to 60,000 labourers were employed at certain seasons. The growers loaded their carts at sunset and between ten o'clock at night and one o'clock in the morning they set out, often accompanied by their wives. 'All the roads round London, therefore, are covered with market-carts and waggons during the night, so that they may reach the markets by three, four, or five o'clock, when the dealers attend.' By six or seven o'clock the growers had sold their produce, which was then dispersed to the retail shops 'by the aid of ill-paid Irish women, who carry loads of a hundredweight to all parts of London on their heads'. The fragile strawberry crop had to be carried into the market as well as out of it, and hundreds of women, many of whom had walked to London from Shropshire or Wales for the soft fruit season, were employed in this drudgery. Like an army of moving caryatids they carried on their heads basket-loads weighing up to fifty pounds, and in the course of the three or four journeys a day which they made from farm to market they often walked thirty miles.2

‘'The epicure may here feast his eyes with delight and, if he is wealthy enough, purchase the natural produce of April or May while the snows of February are whitening the ground.'

Imported foreign produce first arrived at Covent Garden on a large scale in the 1880's and 1890's. American apples, bananas, Tasmanian apples, Californian pears, and early vegetables from Madeira, the Canaries and the Channel Islands were sold.

In 1888, a Royal Commission on Market Rights and Tolls recommended that local authorities ought to be empowered to purchase privately owned markets. Armed with the facts of the report, Sidney Webb of The Fabian Society wrote a damning pamphlet entitled The Scandal of London's Markets.

He began by quoting the evidence given to the Royal Commission that the ninth Duke's average annual net profit from the market during the three years 1884–6 had been £15,000 and stated that this was 'an utterly unjustifiable tax on the food of the people'.

Skip forward to 1920 and things don’t seem to have improved, with the Ministry of Agriculture's committee reporting that Covent Garden was 'a confused and unorganised anachronism’. It took until 1955 for the Government to recommend that a statutory London markets authority should be established.

As photographer Clive Boursnell told me when we met at New Covent Garden, the original market didn’t just take place around the piazza facing the church. Market land extended to The Strand and New Oxford Street. There were banana ripening warehouses on Long Acre. New sites for the market were explored in 1962 and in April 1964 the market authority recommended to the Government that the market should be removed to Nine Elms. The Parliamentary Bill received royal assent on 10 March 1966, and provided for the removal of the market to Nine Elms by the end of 1971.

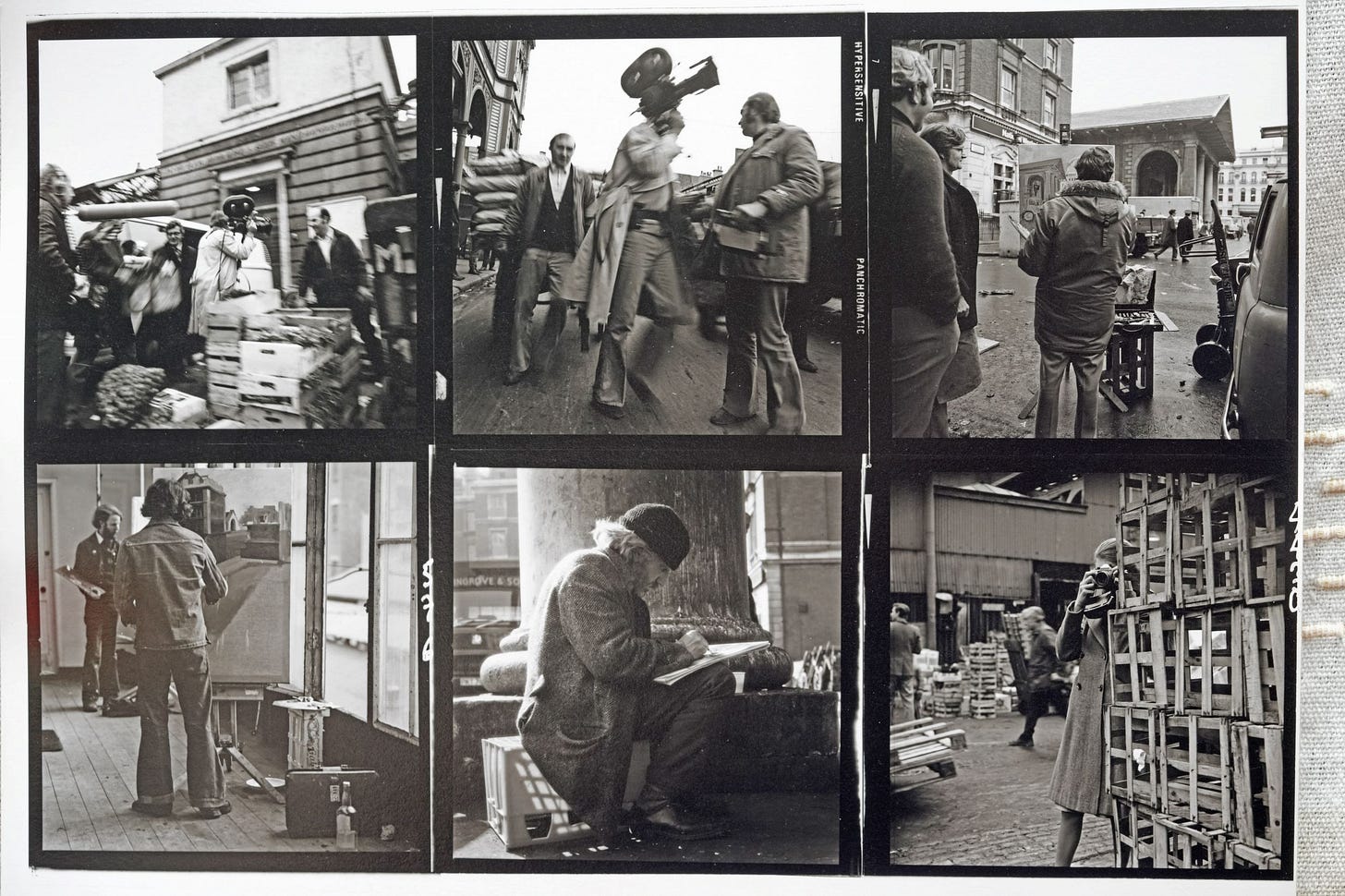

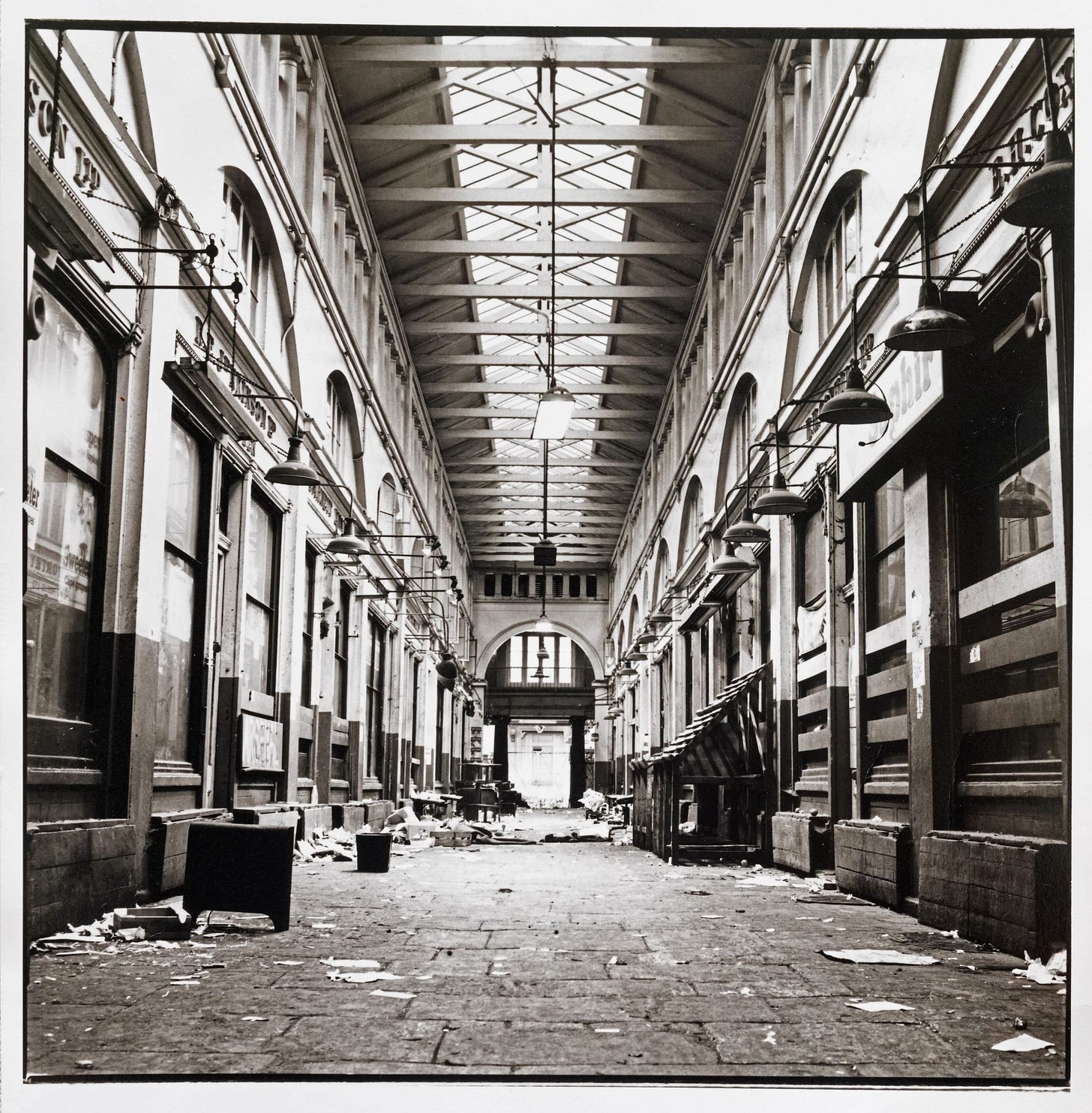

The market officially stopped trading on Friday 8th of November, 1974 – the entire enterprise relocated to Nine Elms in Vauxhall. Clive Boursnell was on hand to record the end of an era and the beginning of the next. The following Monday morning the market began trading at its new home.

The last of the old market porters retired in 2022. There’s no need for them now. So have the formidable ladies creating posies. It’s more like an IKEA than a market, with skyscraper crates of produce up to the ceilings.

New Covent Garden Market is not the only wholesale institution marking 50 years in Nine Elms. On the first day the new market opened its doors in Nine Elms, S Thorogood & Son was amongst the wholesale traders that became new tenants. The expanded Thorogood Group is still a major force at NCGM and also the only wholesale business that today has a presence at all three London wholesale markets; New Spitalfields, Western International and NCG.

Thorogood isn’t a common name. It’s one I remember from running farmers markets when I visited the Thorogood asparagus farm in Essex; they still sell their seasonal asparagus at farmers markets in London.

Will Thorogood is a director of Thorogood and Sons, the wholesale side of the business; there are two other companies under their hat. Rushtons is the catering and food service company aimed at the London hospitality trade, and Mushroom Man, a wholesale mushroom company based at Covent Garden. They also have a distribution company attached to Thorogoods, which has just started going direct to retail and out of London food service.

There’s no such thing as an average working day at NCG. Will gets to Covent Garden about 4am to catch end of night shift and have a debrief. He’ll be on hand to speak to suppliers and teams within the business. Some nights he’ll be working on the stands, wherever he’s needed.

‘‘We’re a 24 hour a day business, 7 days a week, somewhat changing at times. There’s always someone here at Rushtons to pick up the phone.’’

As a family, they've been farming for many years, but the company as it is now started in 1922, and until about the 1980s- 1990s, the family farms were run as a big partnership, proper old-fashioned market gardening,

When they started, crops from Essex and Suffolk were brought up to London, and sold out of then wholesale Borough Market and Romford Market.

When New Covent Garden opened, Wills grandfather moved the company here from Borough Market. Sadly, he says, ‘in the late 1980s, the farming partnership was split up and a lot of them went down a cereal route.’

Will is clearly passionate about supporting UK farmers. His cousin still grows asparagus for them, and they work with farms from all over the UK as well as all over the world.

I want to know if who they sell to has changed over the years. Originally sales were almost all to retail and some direct to consumers. Now the catering and hospitality side has increased;

‘‘on the wholesale side we are now almost exactly 50 50 split between the food service and hospitality sector and the rest of it is all independent retail. So we'll do smaller chains of of supermarkets and green grocers, farm shops and everything in between.

‘‘Chefs are always wanting the newest strangest thing. But retail is probably the one that's changed the most recently. I've realized that the quality, especially the supermarket, has dramatically gone downhill.

‘‘They're so fixated on price that their quality has gone down to meet that price point. So the retail that's doing very well is offering something completely different. A really high quality produce.

‘‘It’s a completely different product. Something as simple as a leek. A supermarket leek and a leek we have here, they’re completely different.’’

To the average supermarket consumer, a leek is a leek but to Will the differences are clear. He has a relationship with his farmers and suppliers, going back 30, 40 years. They know what Will and his buyers are looking for. And they don’t send out anything that they’re not happy with.

Some of the farms he works with also supply supermarkets but as Will says;

‘‘Supermarkets are looking for a different specification, ofton to do with sizing but our supply chain in smaller and quicker. it’s with us within 8 hours of leaving the field and in the shops within 24 hours of being picked, the quality and freshness shows.’’

Challenges don’t change; watching the weather is a constant. The decreasing number of British growers is a real issue for them. Will was at the farm protest in Westminster last week, supporting farmers. He adds;

‘‘They haven’t been able to make money, driven a lot by supermarkets hammering them. They also have big staffing problems. we’ve got great growers but always want more.

‘‘A lot of our produce comes from abroad; it’s more and more of a challenge to get British growers, especially horticulture products.’

I ask if he could have anything to improve his business what would he ask for?

‘‘More good British growers.

‘‘Inheritance tax is the one that's stealing the limelight. It's a bit of a last straw. There's been so many things over the last few years that have made it more and more and more difficult to farm sustainably. It's going to affect the kind of growers that we rely on.

‘‘It takes all the incentive out of invest in a farm from that point of view. And that's going to be very tricky.’’

I want to know more about the family farms. Will is perpetually getting his cousins to try and grow more for them.

After moving into cereals in the 1980’s, some of them are starting to come back.

‘‘My first cousin up in Suffolk grew quite a lot of pumpkins for us this year.

‘‘Some of them are growing potatoes and onions up the market, but looking for my cousins to start growing more vegetables again.’’

If you’re wondering why you can’t find English apples in shops, Will has the answer.

‘‘There aren't enough English apple growers and they're all focused in one area growing a fairly limited number of varieties on a large scale which all get swallowed up by the supermarkets.

‘‘We sell as much UK apples here as we can but that's just not enough to go around, it's the main issue.

‘‘More land is put aside for golf courses than for horticulture. It shows the magnitude of where we are. There are fantastic growers, we’d like more.’’

I suggest that maybe we should see some golf courses turned into farm land!

He laughs; ‘‘I play a lot of golf!’’

After 50 years at NCG, how does Will see the future? Their business hours means that finding staff is ofton a challenge but he says, it looks good. Across the group, they turn over about 40 million across the three companies.

He thinks that high quality retail will continue to get stronger and stronger. Since COVID, hospitality has struggled, but Will hopes they can weather the storm. He wants to help the industry survive.

‘‘Quality is the most important thing for us. And that's going to continue to be so, making sure we provide a different offering and a different product, especially to supermarkets. ‘‘

Over at the old buyers walk I’m meeting Gary Marshall, who runs Bevington Salads and is Chair of the Covent Garden Tenants’ Association. Gary has been here over 40 years. He is keen to emphasis that appreciation for high-quality produce is still lacking in the UK compared to Europe. “People must start to appreciate fresh produce a lot better in this country,” He recently told Fruitnet MD Chris White in a recent Fruitbox podcast.

“In Europe, they all appreciate it. What we expect in this country is cheap, cheap, cheap. What we should be saying, and what New Covent Garden promotes, is quality, quality, quality, taste, taste, taste.”

I ask Gary who the market serves;

‘‘From London Zoo, feeding the animals, to Michelin star restaurants, from small independent retailers to some of the biggest stores in London.’’

‘‘Some begin with H’’ he adds wrly.

‘‘And then we do the boys that are on the stalls and the markets and they've changed the way they work so it used to be we've got the market for cheap second grade product. But now they only sell best. New Covent Garden, having just won the prestigious award for being the best wholesale market in Great Britain, we pride ourselves in our quality and our continuity in our service.’’

There’s a not surprising theme here, that supermarkets have changed not only the way we shop but the way the wholesale markets operate too.

Gary; ‘‘When we moved here 50 years ago in 1974, it had been predominantly sales to independent retailers, a lot of lovely fruit and vegetable shops, etc.’’

‘‘We found in the ‘90s that with the restrictions put in by councils on high street parking making it difficult for people, and the explosion of convenience shopping, the supermarkets come to the fore.’’

‘‘This market had a bit of an identity crisis. So what did we do in the 90s? We re-branded ourselves, remade ourselves, I suppose, into a food service market. So we started serving, and the time was like a perfect storm because people wanted to go and eat out.’’

‘‘Restaurants became very popular, more affordable. People wanted to go and experience different foods, cultures, different types of cooking. So this market with this logistical position, like literally two miles from Buckingham Palace and the Centre of London, that's where we flourished.’’

‘‘We haven't become a one-trick pony. We've still got a very good retail business. When we was all under restriction, where we couldn't travel through the COVID times, people, I believe, fell in love with food again.’’

‘‘We're going to a local green grocer, we're going to a local baker, butcher, to the farm shop and food becomes an experience and consumers fell in love with the fact that they could buy something fresh, cook it, make it and appreciate it.’’

Like Will, Gary agrees that the biggest changes, apart from the times of the market has been the quality. He believes that there’s a great desire for high end produce.

‘‘New Covent Garden prides itself on very high end quality product from all over the world, especially from our British farmers. What you will find is the product you get will be worth it. ‘‘

‘‘We're all very passionate about what we're doing, we're all very knowledgeable and we've spent a long time in it.’’

‘‘The people in this industry are generally very knowledgeable, my son is 28 he’s done a 10 year apprenticeship. you don’t just walk in and understand it. Every day is learning. We serve some passionate very knowledgeable retails. They understand what they’re doing and they understand what their customers want.’’

‘‘We’re controlled by cheap food, cheap food, cheap food. We go abroad and we’re excited by what we see, but we come home and go back to stack it high, sell it cheap and buy a second rate product that doesn’t particularly taste nice, and that’s why you need to go to your local greengrocer, your local farm shop, speak to them, ask what’s in season, what should I be buying now. The same as if going go a butcher or bakers; you get excited just buying it, it’s wonderful. I’m passionate about independent traders because they’ve got this knowledge and they’ve got passion and desire to be the best, whereas the ‘others’ it’s just about shareholders.’’

When I ask what is special about New Covent Garden, Gary says without hesitation; ‘‘community, the people, we've got over 2,000 people working on site, every religion, every culture, no police force here. We’re policing ourselves. And you'll be amazed if you don't actually have any outside interference, how wonderful that is, the community support. We do call ourselves a family here.’’

‘‘If you're having a few troubles or an odd time, just a pat on the back, just an arm around the shoulder could be as simple as that. The way we give for each other. I mean, I've been chairman now for 20 years and I've been through a lot.’’

He’s keen to talk about the achievement they’re most proud of, the money they raise for charity, over three million pounds.

‘‘You know, you've you've seen the market. It's hard nose, people would be walking around, they're trying to get a better deal…but as soon as we say right, we're now raising money for charity, they can't give you money quick enough.’’

Are people are lining up for a job at NCG? As expected, there’s a recruitment problem. Historically it’s siblings, cousins, daughters, nephews who come on board but not everyone wants to work nights.

Gary used to work 15, 16-hour day every day, six days a week. His son George is there at 10 o'clock at night. Their produce starts being delivered to them from 6pm, received by the night staff. Customers start arriving around 10 o'clock. ‘‘10pm till 2am, that four-hour period is when it's out. If you want to come and see a bit of action, that's when it's all happening.’’

‘‘Then you have a bit of a lull in CD2 till maybe 4am, and then you have the people that come a little bit later, which is normally our independent retailers, because obviously they've got to spend all day in the shop.’’

By 6am most warehouses are packed away.

Then the buying starts. From 6am they’re on the phone, speaking to farmers and suppliers all over the world; Spain, Italy, South Africa, Belgium, Holland, UK. George won't get home much before 10am, an average 12 hour day.

‘‘Once you're here, very few leave, once you become part of this family, part of this community, it's quite an incredible, rare thing.’’

It’s on the up, mainly through word of mouth. As Gary says, no two days are the same. ‘‘It's quite exciting. You know you come out one day and you don't quite know what your produce is going to be worth. it is like being on the stock market but more raw because you can’t just leave produce sitting there.’’

He’s managed to recruit under 30’s via his son George who brought in his best mate, now a buyer, and in turn, he’s brought his mate in.

‘‘The average age is now 30 and w’ere seeing that across the market. It’s a massive commitment. You’re giving up your social life but most of the time we’re at home sitting there watching tv which is a waste of space.’’

He doesn’t think that people give enough credit generally to the hard work that goes on not only here, but at other markets, the work that independent traders put in. It’s easy to take it for granted when we walk into a restaurant, or we’re waiting for our hospital or canteen meal ‘‘the effort and the professionalism that's been put together to get that product on your plate. To have received that produce during the night they'll prep it, they'll cook it, it's a wonderful thing and before that, we've had to buy it.’’

For Gary, like Will there’s no love lost for supermarkets. He’s keen to put across the message that British farming is under threat, and not to under exaggerate that threat.

‘‘The biggest destroyers of the British farm are the supermarkets not the government because they are setting them impossible tasks and impossible prices of them producing food. That's why we’ve got no dairy production in this country anymore we lost all the milk.’’

‘‘We’ve got to understand and and be a little bit more respectful to the people that are putting themselves out there, no matter what the weather conditions, whether their fields have been flooded which you've just seen in Spain.

Growers, they've planted their seeds, they've put their whole economic future into that plantation, and it's destroyed by weather. We're susceptible to it. Be careful what you wish for.’’

Given that most consumers demand cheap food, Gary understands that it’s the farmers who absorb the costs. Supermarkets, he tells me, have got them in a net, telling them that they can't charge anymore. ‘‘Although they're making extraordinary and exorbitant prices on their share deals. It's just obscene how much they're earning.’’

(For farmers) ‘‘when you look now at the cost of energy, the cost of staffing, now the NIC contribution, it has to come from somewhere and they can disguise it as much as they want.

‘‘It will come down to the consumers sooner or later because the farmers that are trying to absorb the costs unfortunately won't survive. It's unsustainable. It doesn't matter whether you're a very big businessman or a very small businessman or you've never been in business at all.

‘‘If you've got something that costs you a pound and you sell it for 80 pence, you will not survive. And unfortunately, that is what we are subjected our growers to and our farmers to for many years.

‘‘Across the globe, people cannot afford to sell products and produce for less than it costs to produce. In most of Europe, that is an illegal practice. In the UK, our government, whether it be this government or the previous, are beholden to the supermarkets.

‘‘Running up to Christmas bags of parsnips, carrots, potatoes, Brussels sprouts, are being sold for 10 pence, 20 pence. That is the biggest loss leader ever. The farmer has to support that, and obviously the supermarkets huge profits support that.

‘‘As a consumer of course you're going to say, well, I'm going to go and do my shopping there because it's cheaper. But the damage you're doing…your local green grocer who is buying produce at the real cost, can't react to that. They haven't got tens of millions of pounds in profits to back that up. So we've got to become realistic about costs.

‘‘If you take the time to buy produce that is in season and you prepare and cook them yourselves you can still get tremendous value. You'll get better food and you'll get a better understanding and some of the stuff that we're doing to ourselves to our bodies by buying pre-made, pre-paid and takeaway food. We keep saying how expensive food is yet if you go down a high street it's full of takeaway places which are far more expensive than preparing your food yourself.’’

When Gary opened Bevington in the mid 1980s, they were cucumber specialists, selling thousands, mainly from Italian growers in the Lea Valley. Now they sell a full range of fruit, exotics and, salads.

If he could choose just one variety it would be cherries. Why cherries? ‘‘Because cherries are the only fruit that’s susceptible to the seasons. You can get strawberries and raspberries all year round. Come the Summer, English cherries explode in the mouth, that’s my favourite time.’’

Market manager Jo Breare, General Manager of Covent Garden Market Authority, stops by to say hello.

She talks to me about the market serving most of London and the home counties for hospitality, retail, schools, hospitals, prisons, the zoo, and catering customers. Around 20% wholesalers and 80% catering and distribution, who then serve the restaurants and hotels in London. It’s obvious that customers have changed. She adds that when she first came, chefs were still coming to buy and see the produce. Now it’s store holders, shop keepers, green grocers.

The majority of the ordering and the delivery out is online and on the phone and it gets delivered out to them overnight into the morning. Deliveries might start at 3am, up to midday.

Jo doesn’t think that the produce has changed over the years. She adds; ‘‘I think the demand for it and the quality has only increased. There are other wholesale markets and they deliver a secondary quality, lesser quality than this. We are known for our premium quality and that's what the guys provide on a regular, consistent basis.’’

When I ask how she would describe New Covent Garden, for someone who's never been here, her face visibly brightens. ‘‘ It is a fantastic location that has a fantastic community within it. So we have great produce and a great site that's becoming even greater with the redevelopment, but it is renowned for its quality and service.’’

What about challenges?

She thinks about this; ‘‘That's significant. When I first came here, as I said, a lot of people came to market, but it was moving to distribution far more and it's becoming more prevalent throughout the market.

‘‘COVID had an effect, the 2008 crashes had an effect, the Olympics had an effect with the deliveries having to be so much earlier, they had to be in and out by half past six, that moved hours to earlier in the night and in the morning.’’

Most fruit and vegetable trading is now done between 9pm and 5am, vans on the road between 3am-4am before traffic starts, ready for restaurants.

‘‘COVID drove those times that even further back, plus the difficulties around recruiting staff, retaining staff, working overnight, it's really difficult, it's manual labour, so trying to recruit the workforce is a challenge.

‘‘Pricing is a challenge. Inflation, has risen exponentially, but for these guys, the cost of the product goes up and it goes up. All of the world events have an effect, weather, conflict, etc.

‘‘So they've got challenges, their customers have got challenges, they're trying to maintain their prices or keep them as low as possible. in terms of the increase. They've got the utility price increases, the labour increases, the other product increases.

‘‘People are still working from home, so there's not enough customers. The hospitality industry is really struggling, it’s the markets’ their core customer.

Supermarkets started to do things differently; they set up their own suppliers, bypassing the markets. Buying their own farms. This was before Jo joined the market but she’s aware of the changes it brought ‘‘because they have their own farms, they have their own suppliers who are dedicated to providing and contracted to them. And as she says, that everyone finds it difficult in comparison to supermarkets.’’

I want to know; if you could wave a magic wand, if there's one change you could make here, what would it be? Jo smiles wistfully. ‘‘For London to be back to what it was in terms of events, hospitality, and customers, it's still depressed.’’

There are very few women here; it’s something they’re all aware of and want to change.

At the new buyers walk Dean cheerfully shows me around. Most traders haven’t moved here yet, and building works are ongoing. Dean is a senior salesman for Premier Foods Wholesale where he’s worked for 22 years.

He left school, needed a job straight away and his brother who was already working in the market got him a job loading pallets. Since then he’s slowly made his way up as a junior salesman, as he says; ‘‘ taught by the elders who have now almost left the market.’’

He’s seen a hug amount of change. ‘‘We've gone from an old market into a new market now, which is lovely, beautiful and up to date, which we all have been wanting.’’

‘‘We had COVID where it was very depressing for everyone because people thought they were going to lose their jobs, businesses. But we all pulled through together and we've come out the other end, I think, stronger.

‘‘You get ups and downs in the market. When we had troubles with the banks, it hit the market as well. A lot of things do affect the market. But like I say, together we're stronger.

Like the other traders I spoke with Dean agrees that with times, customers have had to change. He explains; ‘‘With the catering side, dynamics have changed where they've had to move at a time and not just sell fruit and veg.

‘‘We have gone more direct now with growers and farmers, we just don't buy one or two pallets now, we're buying by truckloads so it was easier for us, cost-effective as well as cutting out a middleman.

I get the impression that there isn’t much of a market for organic products here. Dean agrees. ‘‘You still get people wanting it but I think the cost is so high that people realised that it wasn’t cost effect putting it into restaurants, so there’s really not much anymore.

I ask if he could make any change what would it be but Dean seems happy with the way the market is progressing.

‘‘Everything is running smoothly and it is what we want it to be. We don’t know what’s around the corner but I’m happy the way things are.’’

Morning light is starting to filter in, as I make my way from buyers walk to the Flower Market building. I’m meeting Tommy Leighton, Communications and marketing for NCG, and photographer Clive Boursnell, camera slung around his neck, ready to go.

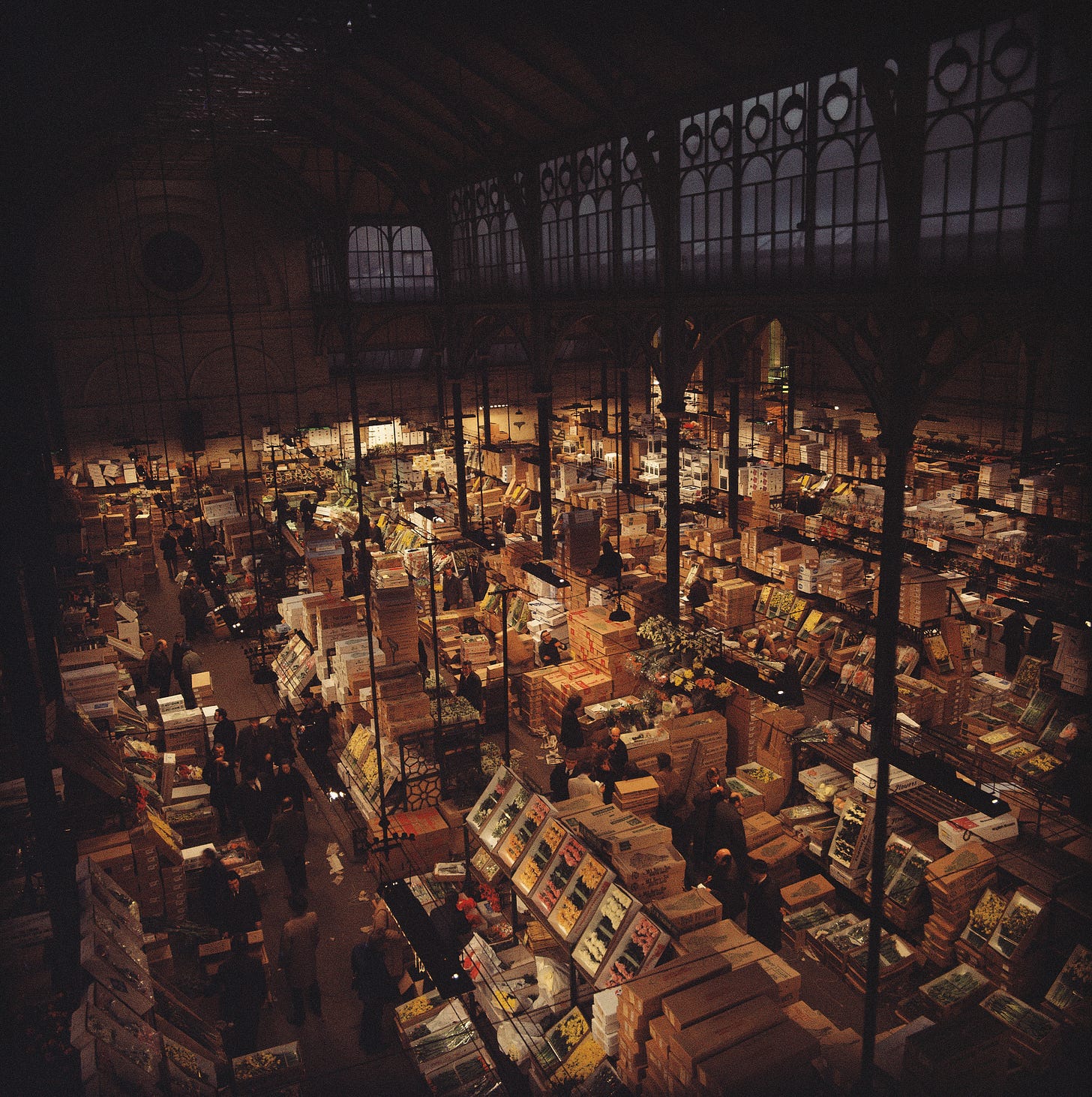

Clive worked as a woodsman on the Windsor Estate in 1957, taking Christmas trees to George Munne at Covent Garden market. He later became an assistant photographer based on Great Queen Street, just around the corner from the market. He started taking photos of the market in 1968, spending a year ‘‘getting to know the market and having the traders ignoring me’’. Just what a photographer wants; to be trusted and invisible. His carefully framed photos capture moments in time and cover the walls of the flower market cafe. There’s a lovely little film about him here.

Tommy has been working at NCG for 3 and a half years. If you’ve seen the market on the news or pictures of animals at London Zoo eating fruit and vegetables from the market, it’s down to him. He tells me; ‘‘I love the market, I’ve got a passion for this place. The 50th anniversary fascinated me, the link back to the old site. Covent Garden is a brand and we don’t treat it as a brand enough, we should do. People around the world know it. It’s been a chance to speak to people around the world.’’

It’s clear that he wants the 50th anniversary to enthuse the media, but not only that; to give credit and recognition ‘‘to the people who are here an incredible, 6 or 7 days a week, lots of them for 30, 40, 50 years. This market is a fascinating place, people don’t realise what’s behind the walls. It’s not always an easy sell. We’re basically a wholesale market in south London operating in the middle of the night.

Moving forward he’d like people to realise ‘‘what value we bring. When we’ve completed our redevelopment in 2027, this site is going to be here for a long time to come, it’s going to underpin the fruit, veg and flower supply chain in London and the SE for years and years to come. A lot of tenants would say we need to bring in new customers to the market; that’s easier said than done, ofcourse we hope that what we’re saying entices people into the market. If they come they’ll never regret it, if they start working with the guys here, they’ll never stop. We’ve got to get them here in the first place, so we understand the difficulties.

Similarly to farmers markets, Tommy wants to put across the value of finding smaller brands that don’t exist in supermarkets.

Given the new buildings going up, I want to know if New Covent Garden will ever outgrow this location?

‘‘That's an interesting question to start with. I don't know, there's the honest answer to that. The redevelopment has reduced the footprint of the market but it hasn't reduced the trading area so when the redevelopment has finished in 2027, the market will certainly fit into it. Whether some of the traders become bigger than they are now and move out to the market to other facilities as well is a slightly different question to what you're asking.’’

He says he thinks that the vast majority of the traders, if not all of them who are here at the moment, recognise the value of being in this location and the value of being in a market rather than being at a distribution site.

‘‘It’s a fully functioning market and I don't see why that would change anytime soon.’’

Like everyone else I’ve spoken with, Tommy emphasises the quality of the produce sold at NCG and what it needs to flourish; skills, experience, supply base and premium, fresh produce. flowers, plants and foliage.

‘‘You can't sell anything but premium here, that's what we're renowned for and that's what we're set up for so we need those customers to thrive and we need to be able to help them to thrive and support their customers in building their own businesses rather than just supplying them with products. Wholesalers, catering, and the floral designers work very closely with their customers to make sure that they're giving their customers exactly what they need to make them successful and that's what we need; we need a successful customer base otherwise we're nothing.’’

He doens’t think that the market is competing with supermarkets. ‘‘Our customers are to a certain extent. But because we're so dominated here on a food front by catering, that's not in competition with the supermarkets. The competition for the catering food service hospitality are the national distributors of food and veg, people in other wholesale markets as well, but mainly the national distributors.

‘‘We’re in a perfect location, a lot of our customers are independent rather than chains we can serve them better than national distributors. From a flower point of view, you can select it yourself, talk to knowledgeable traders. Online you can’t see it, or smell it before you get it. It’s the senses if you come to the market direct.

Given comments from the traders about British supplies, does Tommy think that the market can increase the amount of British produce coming into London.

‘‘We sell as much as we can’’ he says, ‘‘depending upon price and availability. These guys are traders, working on different margins depending upon the time of year. It’s a business. They support British growers to a fault, always will do but it’s a 2 way street. The supply and the price.’’

‘‘In the flower market the supply chain for flowers is more dispirit. They want to sell more British because there’s a demand but if it’s not available at the right quantity and the right price, they can’t sell it.’’

Sustainability is a word that gets bandied around a great deal; how does the market define it, and what does it do? NCG has a zero to landfill policy.

Food waste that is no longer fit for human consumption goes to anaerobic digestion. All organic food waste is collected daily by Bio-collectors, one of the only Anaerobic Digestion sites in the UK certified by the British Gas Council to provide bio-gas directly into the National Grid. The process also produces a nutrient rich fertiliser from food waste, called digestate. Around 200 litres a year of cooking oil, from the on-site cafes, is collected in drums and given to a biofuel producer.

Between April and July 2024, the carbon savings made in the market were equivalent to, amongst other things; Charging 379,110,515 mobile phones, saving 43 mature oak trees and 3,117 return passenger flights to New York

Charities based at NCG include local charity Waste Not Want Not, Food Cycle, City Harvest, and Floral Angels, who redistribute unused flowers. Around 15 charities use the market on a regular basis.

City Harvest go around every morning to talk to the traders, ask them what they've got available. They collect it, and truck it off to Acton where it's all processed into meals. Several tons a week of perfectly good produce that would probably go to waste.

Tommy tells me that the market has been looked at as a case study by some of the train stations in London. ‘‘How we do things. So we're doing it properly. We're just actually just not very good at talking about it at the moment, but we will be. That's where we need to get to.’’

Whether a produce is shipped or air freighted is at the top of every traders minds because every single customer is asking. Tommy says ‘‘There’s hardly a chef in london who doesn’t ask about sustainability credentials. Some more than others, but everyone is asking. Even if the customers aren’t asking, the traders know.

‘‘If our tenants are asked for it they’ll sell it. We can’t only sell shipped products. There aren’t many restaurants that only use British products because they wouldn’t make a living, but there are some that major in British products.

We’re here to supply what the customer wants.

Supermarket say that they put what the customer wants on their shelves. That’s not true. They sell what makes them money.

So many people take the market for granted, what would happen if the market didn’t exist, who would lose out?

‘‘It would leave a massive, massive hole in the food and flower supply chains for London and the South East in particular.

‘‘It wouldn't be replaceable overnight. It would need a hell of a lot of work for people to put all that in place. You could argue that all of the traders here could move somewhere else and do it themselves.

‘‘But they wouldn't be part of a market anymore. So they'd have to do a lot of work to get themselves into a position to be able to carry on what they're doing now. The London restaurant trade would be hugely poorer for it.

‘‘The Michelin star chefs, all the top end chefs that use this market, rely on this market to supply them year round. Yes, they could source products year round from elsewhere. But the availability of the breadth of product that they need and the breadth of product that they use to make their incredible dishes every single day.

‘‘It might be there, but it'd be a lot harder to source it. The independent retailers, there's a lot less of them than there used to be, but the ones that are still here are also fairly high end and are doing an amazing job.

‘‘Because they're competing with the supermarkets, with the caterers for people's money. They do an amazing job. They buy their product from here because they know that they're getting the best. They know that the product they're going to be able to put in front of their customers is going to be spectacular.

‘‘If this market wasn't here there are two other markets in London. If you took all three markets out of the equation you're taking two billion pounds worth of fruit, vegetables and flowers out of the market every year. As much as we know we can rely as consumers on the supermarkets for the big weekly shop, there are always times when we want other other products and there are plenty of people who don't go to supermarkets who rely on their independent retailers to supply them and all of their products, and places like Selfridges and Harrods and the high-end retailers, and restaurants. They need this market. Without it, the world would be a poorer place.

‘‘wholesale markets all across the country are so important, retail markets are still the fabric of so many societies around the country and we can't lose them, we shouldn't lose them.

‘‘Even the supermarkets need something to compete with, so however they think they're competing, they think they're competing with each other all the time, you know, matching the price of Aldi, matching the price of Lidl, consumers aren't stupid, you know, we know that that doesn't really mean anything.

‘Supermarket say that they put what the customer wants on their shelves. That’s not true. They sell what makes them money.

‘‘This market allows people to compete on quality. better than any wholesale market has been able to do ever before. It’s really important that you compete on quality and in terms of the highest quality we do it best here. You have to buy what you think your customer will buy from you. Supermarkets do that up to a point. The difference is, when shelves are empty in supermarkets, it’s not because that product isn’t available, that product is here, it’s because they won’t pay the price they need to pay. Our traders continue to buy.

John Hardcastle is busy at his computer at Bloomfield Wholesale when I go over to talk to him. Born in Islington, he spent his childhood in Covent Garden, living above the market, up until he left there at the age of 18.

Selling at the original Covent Garden was ‘‘Absolutely fantastic. Quite different but these was different times. I couldn’t have had a better playground to have grown up in, that's for sure.

How has the market changed? ‘‘Just look on your average high street. How many street traders are there? Flower stores, fruit stores, they don't exist anymore. The whole job has become sanitised, same as the high streets I think.’’

John believes that the people they’re selling to has changed. ‘‘Very much so. Again we used to sell to street traders. They’re a big part of our business so it was a little bit rough around the edges and not quite what it is now.’’

‘‘As a company we're mainly party planners, event organizers and then we've got our contract florists who take care of hotels, restaurants. A very small part of our business is the retail side.’’

Anyone can come and buy flowers. ‘‘We love seeing anyone. There's no need to get here at ridiculous hours if you're general public, we're open to about 9.30am most days. You don't have to buy whole crate of flowers, no. You have to pay your VAT though, I'm afraid.’’

When I ask if he was pleased to move here from Covent Garden he says;

‘‘I can't say we were pleased to move here. It was a necessity. But when we originally moved here to Nine Elms, it was a wasteland. We had been dumped in this strange part of South London that none of us knew with no bars, no pubs, no restaurants.

‘‘And you can see the change now, obviously. It's the place to be now. But 40 years ago it wasn't. We need to be out of this building. This building is a temporary building.

‘‘We need to be in our permanent home so we can make our plans for the future. We've been here coming up six years now. I think we're looking at another two at least.

‘‘COVID put the kibosh on everything. We’ll get there. We’ll get there.’’

It’s clear that everyone I’ve spoken with is proud of the history and heritage of Covent Garden. It’s obviously tough working nights, but the camaraderie and perks make up for it.

Last word goes to Gary.

‘‘This place is bloody special, if there are any young people out there looking for a new career and they've got a little bit of fire in their belly and they don't mind working through the night when everyone else is asleep, there's a career here, there's great opportunity and phenomenal rewards, because if you're good at this, if you come to work here and you work hard, you get the right rewards. What's great about New Covent Garden? The people.’’

If you want to visit New Covent Garden, opening hours are Fruit & Vegetables

Fruit and vegetables Monday to Friday 10pm - 6am, Saturday 10pm - 5am

Flowers Monday to Friday 4am - 10am, Saturday 4am - 9am

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol36

Sir Richard Phillips, A Morning's Walk from London to Kew, 1820, p. 224.

If I remember correctly, the original site was once a convent. When King Henry VIII kicked the nuns out it was left to decay. Back then it was in the countryside so not worth much. But local villagers took the opportunity and used the land to grow vegetables etc, and then they started a little market. So it became known as Convent Garden, and obviously over time, Covent Garden. I think!

What a wonderful read. Thank you.