Who killed bambi?

Exploring our love/hate relationship with venison and why we should Be More Wolf.

Welcome to today’s’ piece, a deep dive into wild venison. It’s a bouncing, pronking tour along the glades and woodland pathways of venison history, attitudes towards eating it, sustainability, management and a rather extraordinary way to look your meat in the eye. Yes it's a long read. Think of it as a chapter in a book I might one day be writing. No piece next week so you’ve two weeks to digest it.

I’d love to have your feedback. I know it’s a pain to leave a comment or like if you read this via email rather than on the app but feel free to reply to this email and I’ll get your message.

As always if you can, the best way to support me is to upgrade to a paid subscription or pop a tip in the coffee jar, always appreciated for the work I put in.

the UK’s deer population is estimated to stand now at its highest level for 1,000 years; there are more deer now than when William the Conqueror arrived.

Deer have been part of our landscape since the Ice Age. In the UK we have two native breeds, red and roe. Fallow deer were introduced by the Romans. We also have invasive, non-native sika, muntjac and water deer. Deer live in the wild, parkland deer are found on huge estates or in parks such as Richmond in London, and farmed deer are exactly that; kept as farm animals and not classed as wild.

The British Deer Society have the clearest up to date data and maps that show distribution of species. Have a look. You’d be surprised how close you may be to a deer.

The wild deer population is so high it affects the eco balance of our woods, forests, and landscape. Deer management includes culling to keep the stability. With that cull we have a ready supply of lean, healthy, sustainable meat that should be available in every hospital, school, butchers, neighbourhood restaurant and canteen around the country, but isn’t.

Most of the venison sold in supermarkets is either farmed in the UK or imported from New Zealand. The total UK venison market is estimated to be worth £100m. Until BREXIT the majority of venison produced in Britain was exported1

Two years ago in a House of Commons debate on deer management, Sir Charles Walker said2;

‘‘At around 2 million animals, the UK’s deer population is estimated to stand now at its highest level for 1,000 years; there are more deer now than when William the Conqueror arrived. Our immense national herd keeps on growing. To put that in context, to keep it stable at 2 million, we would need to cull between 500,000 and 750,000 deer each year—that is just to keep things stable. At present, however, we are culling only about 350,000 animals, so each year the national herd keeps growing, and more trees and crops are nibbled away3

Why aren’t we eating more venison?

Is it still a class thing? Do we think it’s too expensive, not for us, too ‘gamey’ too tough, too much of a treat, not an every day meat? Culturally and socially, who eats venison? If it’s on a menu is it often the most expensive item? Is it because wild deer are hunted? The concept of venison being just for the rich has hung over our heads for too long.

The name Venison comes for the Latin word Venari which means to hunt or pursue.

The Romans brought deer parks to the British Isles, but the Normans expanded the number to between 2,000 and 3,000 parks by the 12th century.

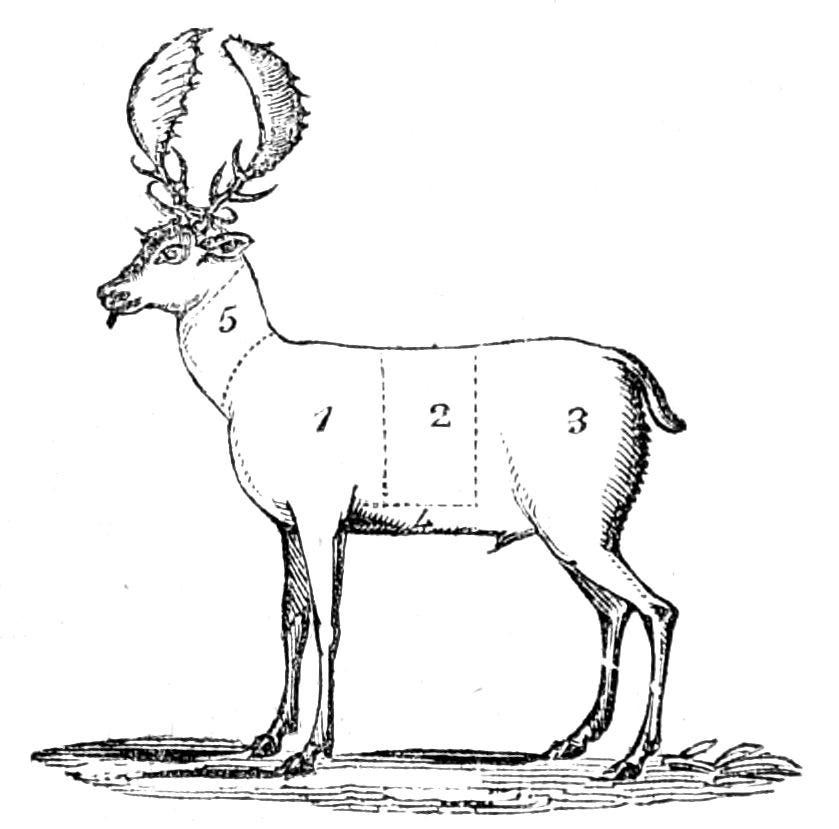

In the ancient method of ‘unmaking’ a complete fallow deer — a flamboyant medieval ritual, a deer is skinned and butchered and then divided up among the community.

Different parts of the deer carcass were destined for different purposes. The pelvis bone was for the crows and/or ravens, the left shoulder for the hunter or the ‘unmaker’, the right shoulder for the forester, and the haunches for the lord.

Unsurprisingly, the peasantry was segregated from such activity and had to resort to the great risk of poaching to obtain its share of wild game. Dr Naomi Sykes, of Nottingham University’s Department of Archaeology, says ‘‘modern deer management problems are a legacy of the medieval period, so perhaps we need to look for medieval solutions… Hunting fell out of fashion, people lost their taste for venison and the deer parks fell into disrepair. Their inhabitants escaped into the countryside and with an absence of human and other natural predators — British bears, wolves and lynx had been hunted to extinction by the 13th century — the deer were left to breed.”

We eat venison, not deer meat, just as we eat pork, and not pig, beef, and not ox. The Norman invasion changed our language, and it’s never returned. They also meted out fierce punishments if you were caught poaching the kings deer. Robin Hood may be a legend but the stories about being hung for poaching, or having a hand or ear removed, are not.

In New Forest Commoner; William I introduced forest law to protect the ‘venison’ (game animals) and the ‘vert’ (the vegetation and herbage the game animals depended upon for food and shelter) in his hunting reserves. So severe was forest law that it was reported it was designed to ‘leave the English nothing but their eyes to weep with.’ Disturbing a deer meant punishment that included blinding or having a hand cut off, and actually killing one, even to feed hungry children, could lead to execution.

By 1217 the death penalty for poaching in the New Forest was abolished. The 1215 Magna Carter states;

‘‘Henceforth, no man shall lose his life or suffer the amputation of any of his limbs for killing our deer. If any man is convicted of killing our deer, he shall pay a grievous fine, but if he is poor and has nothing to lose, he shall be imprisoned for a year and a day. After the year and a day expired, if he can find people to vouch for him, he shall be released; if not, he shall be banished from the realm of England.’’

Poaching had always been considered a social crime and the laws around poaching continued to be unpopular because it was felt that poachers were just poor people who needed food. The law existed to protect the wealth of landowners and the death penalty was too harsh a punishment.

Deer are protected by the Deer Act 1991 which criminalises various activities including poaching deer and the use of certain ammunition in hunting deer and the Hunting Act 2004 which bans hunting of mammals with dogs, but they can currently be legally hunted in certain circumstances at certain times of the year.

Thousands of folk songs exist, with poaching as their theme, often telling tall tales of exploits, foiling the game keeper and the tension between the landed gentry and working class.

Many people are breaking down barriers, both in shooting, and eating game.

Nicole Moore who writes as Shooting Girl with an Afro says on breaking down stereotypes;

‘‘The shooting community…have a much broader 'judging stick' that I have found both useful and disarming; can you shoot (yes) do you care about nature (yes) and do you like jokes (yes). The end.’’

SJ Hunt CEO of The Country Food Trust thinks that perceived class lines are shifting and changing. ‘‘We’re more aware of provenance.’’

Founded in 2015 the sole aim of the Trust is to feed people in need by producing game based ready meals which they distribute to charities helping people in need in both urban and rural communities. From inception they have now supplied more than six million meals. 650 tons of meals in 10 years. SJ Hunt is keen to emphasis that ‘‘People always ask for more.’’

The trust has worked with about 1,000 charities and food banks, providing them with butchered frozen meat in 20 kg blocks that can be broken down and turned into casseroles and stews, or their own brand, long-life, pre-prepared meals.

In February 2023 the Trust were about to deliver their 3 millionth meal.

She told me; ‘‘Stalkers won’t kill a deer unless they know where it’s going.’’

Why are we so squeamish when it comes to eating deer meat? Is it the cute factor, or fear of something that’s unknown?

SJ Hunt says firmly;

‘‘When people say I don’t eat Bambi, I’ll say, you’re okay eating other cute animals.’’

Come dine with me on Channel 4 features 4 contestants taking it in turns to host 3 strangers and cook a 3 course meal for them. One of the saddest continual reactions is from the guest who ‘won’t eat Bambi’ when presented with a menu containing venison. Either they’ve never seen, or tried it before or they think it’s too posh. Or it’s too cute to eat. Never mind that they’re happy eating cute chickens, lambs and pigs.

The Bambi factor continues on, from those who see deer as cute, to those who think all deer should be preserved at all costs.

Seven years ago a petition to stop culling animals including deer in London’s royal parks amassed an incredible 138,890 signatures.

Why does it matter how many deer there are?

8,000 hectares: The area of woodland with Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) status that is currently in ‘unfavourable’ or ‘recovering’ condition due to deer impacts. (BBC Countryfile)

£4.3m a year: The cost of deer damage through eating and trampling crops, according to Defra, with the greatest damage on cereal crops in east and south-west England. Deer will strip bark and browse shoots.

50%: The decline in woodland bird numbers where deer are present, according to the University of East Anglia’s Dr Paul Dolman: “Deer will eat the understorey and so the coppices, for example, lose their shrub layer. That can be a problem long-distance migrants, such as willow warblers, chiffchaffs and blackcaps.

Research by the British Trust for Ornithology has found that common species including robin, wren and blackbird are less likely to be in woodland areas browsed by deer. Some of our most vulnerable breeds, such as nightingale, nightjar and woodcock, are also negatively affected by deer grazing and browsing.

Large populations of deer are likely to contribute to the abundance of ticks, parasitic insects that can carry diseases such as Lyme and TBE (tick-born encephalitis) that are a threat to public health. Deer may also carry parasites or diseases such as foot-and-mouth and bluetongue which are a threat to livestock.

Deer are the cause of almost 70,000 accidents on Britain’s roads every year.

Overgrazing impacts woodlands, reducing both animal and plant diversity. Bluebells are one of muntjac’s favourite meals which means that an over population of these deer can devastate bluebell woods.

Sustainable deer management is necessary to keep the population in balance with nature.

The British Deer Society, opposes a widespread cull but agrees with localised, targeted culls. They state that-

‘‘The population of the six wild deer species have grown significantly in recent decades. The term “overpopulation” is often used, but it is a human construct, shaped by perceptions of what is acceptable rather than natural. While large deer populations can present ecological challenges, it is not the sheer number of deer that causes issues but the negative impacts they can have, such as over-browsing and habitat degradation.

Culling—planned population reduction—remains the most effective method to manage deer numbers. It reduces damage to vegetation, limits biodiversity loss, and mitigates agricultural impacts. Culling can be targeted to address specific factors, such as age, sex ratio, or health, ensuring a balanced approach to population control.’’

‘‘Without predators, deer in a given woodland population will steadily strip the forest bare before starving due to lack of resources.’’ says Stephanie Bale from Ethical Game.

‘‘The population crashes alongside other wildlife in the forest, which allows the forest to regenerate, which allows the deer population to increase, creating a boom and bust cycle that never ends and causes serious long term damage. For this reason, most managed woodlands have cull quotas, often of several hundred animals per year (usually 30% of the herd which increases by as much as 60% a year) – meat is a by-product of shooting, but deer are not shot for food.’’

Stephanie also adds; ‘‘When customers say they don't want to eat bambi -we say that we are not eating bambi (a baby deer) unlike the farming industry that does eat babies like your 13 week old heavily obese broiler chickens. Deer culls do not usually include baby deer.’’

More from her later.

Next year The Countryside Trust will be exploring using halal venison to expand their market. Because wild deer need to be killed with a rifle, I’m curious to know how halal, and kosher venison fit into this category.

Geoff Wickett of Chiltern Venison has been stalking for fourteen years. He began at school, then had a career in the infantry. He accompanied a professional stalker fourteen times, alongside taking his qualifications in deer management and formal training as a stalker.

To him as to every other person I speak to, the real purpose of stalking is conservation.

He shoots around 160 deer every year. Mostly fallow but also some Chinese water deer and sells to local pubs, restaurants and local farm shops and takes orders direct.

‘‘A wild animal belongs to no-one.’’ he tells me. ‘‘As soon as it’s shot and hits the ground it belongs to the landowners.’’

What happens to the skins?

Nothing. He says; we don’t have an industry for them in the UK. It’s heartbreaking; yes there are small scale tanners but nothing large scale to cope with the number of deer skins available.

He’d offered to devise a training course to a group of local Muslim boy scouts but they didn’t get back to him, although lots of local people he’s spoken to are keen to source halal venison. He says there are different interpretations. So, what makes venison halal?

Oakland Park is a wild game processing plant and deer conservation reserve near Newbury. They only work with locally sourced game and only with hunters registered with them. Newly opened last August, and with the aim of trying to get more venison into commercial markets, owner John Prince tells me they’ve already had a turnover of £1.5 million. They’ve provided between four and five tons of venison mince for The Country Food Trust.

To meet the growing demand for halal-certified venison, John has undergone specialist training provided by the Islamwood Foundation. The facility, including its hunting and processing operations, has been certified by the Halal Certification Organisation (HCO). All halal-related activities are carried out in dedicated areas in accordance with Islamic principles and global halal standards, and the operation is regularly supervised by HCO auditors to ensure compliance.

As well as being a processor, John is a trained stalker. Hunted in a specific way, to make a deer halal, a shot is taken, with a prayer spoken when taking the shot. The whole process needs to be separate from non halal products from start to finish.

They’ve just finished their season as ‘‘no one wants the deer that have a longer/no season; there’s no market for roe or muntjac. Most restaurants want larger cuts or won’t take whole carcasses.’’ Sounding more hopeful, he mentions that a football stadium is looking at them providing venison for burgers; 70% venison, 30% beef which would be a huge order.

He thinks that class distinctions have gone and adds that it’s a strange illusion that game is too rich.

The Kosher Rare Meat Company didn’t respond to my request for comments. It won’t be kosher if a deer is shot and killed with a bullet so I’m very curious to know where they’re sourcing and how. They’re importing it, and I’m assuming that it must be farmed, not wild.

It’s difficult to hear that venison is sometimes discarded instead of being eaten. Stephanie and Alan of Ethical Game are unique; they use every part of the deer that come her way, ‘‘taking and processing the whole animal, including meat, bones, hide, and tendons.’’

Stephanie Bale explains:

‘‘Stalkers in the UK typically have a quota they have to fulfill every year to cull the deer herd. If you own land with deer on it, its basically your legal responsibility to also manage the deer herd. Deer populations increase by something like 30% minimum every year and without natural predators, this has quickly become an environmental disaster. So land owners must cull a certain number of deer every year as calculated based on the estimated size of the herd on their land. Even so, it's never enough and the population has been steadily rising for some time now.

Stalkers usually have to either pay to shoot on the land in return for managing the deer population and meeting that quota, or they are outright employed by the landowners to meet that quota.

‘‘When we first started this business, the stalker we were using was throwing away around 300 deer per year because he couldn't find enough buyers. In lockdown things had become much worse, with restaurants closing and the general populace not consuming deer, so many butchers have chosen not to stock it or to just sell fillets at a high price. But he still had that quota to fulfill (for the sake of the deer, the woodland and the other wildlife as well) and the populations was worse than ever. That's why deer ends up going to waste. Not every deer does, and many people like ourselves have been working hard to limit how much waste occurs.’’

Alan adds that sometimes game dealers will reject a carcass for no reason. Sometimes a deer may be left in the forest floor, or goes for pet food. Hunters will always avoid having no market but a game dealer may only offer a low price, 30p-50p per kilo for example. At Ethical Game they offer a year round £2 per kilo to help stalkers meet their quotas, and sell their deer for a fair price.

After a successful cull, deer are gralloched4 in the field right away for food safety reasons, then transported back to a walk in chiller and hung until a buyer can be sourced. A deer can be hung for around 2 weeks in a fridge before it should be discarded.

What happens to the rest of the deer?

’’Leg bones are used for stock. Pelvis bones we keep for our dog who devours them in seconds. The only bones we cannot save are typically the ribs.’’

Joints are frozen and boiled to make hide glue. Deer hair makes paint brushes for their personal use only. They save the fat for candles, soap, and making salami, chorizo, haggis, black pudding and refine it into tallow as a cooking fat. - ‘‘A really healthy fat high in stearic acid to reduce cholesterol and a really high smoke point making it excellent for roast potatoes (better than goose fat!).’’

What blood they get they save in the freezer to make black pudding. Pluck (stomach, intestines) has to be discarded in the field unless they can cool it immediately.

‘‘Last year we managed to wrangle 30kg of pluck and made around 200 haggis!’’

They don’t have the facilities for processing skins on a large scale but several skins are turned into buckskin to make pouches, a waist coat and moccasins.

‘‘Our aim is to use them to teach others how to do this as opposed to selling the products themselves. We are trying to work with local bushcrafters and artists who want excess skins and provide them as is for free where possible.’’

‘‘On rare occasions when we get a head, I will pop it in my compost and return to it in a few months to clean up. This is then either sold as is - natural, or I will have a play with artistic materials and then sell it. My last skull was dyed black, teeth kept white and then the antlers covered in gold leaf. It was quite a statement piece.’’

Why isn't eating venison ‘normal’?

In 2023 the UK Government introduced a quality assurance scheme for wild venison in association with game dealers and shooting and conservation associations to develop new markets and promote British wild venison. The idea was to raise awareness of venison with the public and to increase the supply of venison into supermarkets.

There are various projects around the UK to encourage more venison onto menus with news about venison on nursery and school menus, hospitals. But not enough.

In an article for Farmers Guardian, Alexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, said: "Amidst all discussions about the need to increase our food security, one of the healthiest forms of protein is in abundance with supply of venison far outweighing the capacity of existing domestic supply chains to get it to market.

"NHS England has successful pilots with Forestry England, but this only scratches the surface. To make a broader domestic supply chain a reality, investment is needed in regional processing facilities that farms and estates doing the essential work to maintain the wild deer population at a sustainable level can look to collect carcasses. "It is not pie in the sky; it is achievable. And there is no reason for anyone to argue that price is a barrier.

"Venison is seen as a luxury item on hospitality menus but with the deer population at its current levels, it must be possible to process at a price point that would make it an affordable form of protein for school and other public sector caterers.’’

Eat Wild, are also on a mission to get wild game onto more plates and supermarkets report an increase in sales of venison, especially burgers and sausages.

It doesn’t have to be fancy. As chef, food writer and wild game champion Rachel Green points out,

‘‘venison doesn’t have to be special occasion food. It’s available to everyone. If people say ‘it’s a bit posh’; it isn’t. It can be a venison bolognese or a lasagne. Lots of people are on a budget. Keep it simple..’’

On an Eat Game podcast, Rachel says it’s a bit of a middle class affair; ‘‘there are campaigns in schools for teaching children about game, but it needs to be across the board.’’

The ‘deer hunting season’ is divided into three phases. From early August until the end of October mature stags are hunted, from November to early March hinds are hunted, and during March and April young stags are hunted. Scotland allows occasional licences for hunting out of season. The only species without a fixed season is muntjac which breeds all year. Because only male roe and muntjac bridge the wider hunting gap, more education and training is needed to persuade restaurants and caterers to take whole carcasses, including roe and muntjac when available, to use every part and for more frozen venison to be used. Alan Bale from Ethical Game points out that it’s hard to shoot roe and muntjac in any number to make it profitable. And for him, skinning deer outside, fighting off wasps and flies on a hot summer day isn’t pleasant.

How does a deer stalker feel when they shoot a deer?

Dartmoor based Sharif Adams carries out annual assessments and drone surveys for landowners, to inform evidence-based deer management practices, ensuring that deer are managed humanely and sustainably while reducing potential negative impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity.

As a nine year old he developed an interest in foraging and wild food. Air rifle hunting taught him about the ethics of hunting to provide sustainable wild food. In his thirties, he moved to Dartmoor and lived off-grid for five years exploring ways to be self sufficient. A deer stalker taught him about deer and why in the absence of natural predators they need to be carefully managed - for the health of the herd, to minimise the impact on woodland flora and fauna and to support biodiversity.

‘‘It seemed logical to me that I should train to become a deer stalker so that I could contribute to the important conservation work my mentor was doing and at the same time provide healthy, sustainable and ethically sourced venison’’

‘‘As a young boy in Jordan I grew up knowing exactly where our food comes from. I didn't realise at the time how so few people in the western world ever really experience this; to most people meat comes from supermarkets, neatly wrapped in cellophane and the messy bits along the way are never witnessed.’’

He remembers the first time he shot and killed a rabbit he cried.

‘‘That was forty years ago but I remember it as if it was yesterday. There was a profoundly different connection to and gratitude for that rabbit as food compared to anything else I had ever eaten.’’

What does he feel about the concept of class distinctions when it comes to deer stalking, and eating/buying venison?

‘‘Deer stalking used to be considered a 'sport' for wealthy people but this is certainly not the case anymore. While it may still be a hobby for some people, it is increasingly being recognised that deer stalking is hard graft and essential conservation work. Good deer management has nothing to do with ‘trophy hunting’ or indiscriminate shooting of deer. A growing number of seriously committed men and women from all walks of life have a genuine interest in deer welfare. They work hard in all weathers to ensure that wild deer populations in the UK are healthy and in balance with their environment. ‘‘

‘‘Some people still think of venison as an expensive, luxury food item. In my opinion this needs to change. Venison is a healthy and ethical food which we should all be eating more of, particularly when it's so easy now to buy local wild venison at a sensible price, often direct from a local deer stalker.’’

Has he ever come across any vegans who've eaten venison?

‘‘Several of my regular customers are vegetarian or vegan. People who take a little time to learn about the reasons for deer management generally understand that venison from wild deer that has been sourced locally by a trained hunter is among the most ethical and healthy food you can eat. UK wild venison is low carbon, free-range and naturally lean. Buying local venison means supporting trained professionals who manage deer humanely and it helps reduce food miles and our reliance on imported meat.’’

Would he ever shoot a deer on request, not knowing what is going to happen to the animal?

‘‘I shoot deer according to a carefully considered deer management plan which is based on in-depth annual ecological assessments of deer impact and annual counts of deer. Our team studies the impacts deer have within woodlands and we use sophisticated drones with heat-detecting (thermal) cameras to count deer and build an understanding of herd structure (species, age and sex) at a landscape scale.’’

The data they gather allows them to understand the level of impact the deer have and

‘‘whether or not we need to shoot deer at all and if so which age and how many males or females to remove from the population to keep the herd healthy and in balance. ‘‘

‘‘I know my customers and I take an interest in where the venison I sell goes. I write a newsletter when we have venison available. I let people know about the work I do, why it is important, how it is contributing to support the health of our woodland flora and fauna and I hope I also convey the respect and passion I have for the welfare of our wild deer.’’

How does he feel making a kill?

‘‘I always feel a combination of regret and relief when I shoot a deer. Relief that the shot was good and the deer was killed humanely. Regret at having taken the life of a sentient animal. This is entirely appropriate. If I didn’t have an emotional response I would question whether I should be doing what I do.

‘‘Something that people who do not hunt will always struggle to understand is that good, ethical hunters love the animals they hunt. It is only natural that people who spend their lives studying and observing an animal will come to feel a strong affinity with it.

Our ancestors were all hunter/gatherers and we know they had the deepest respect and reverence for the animals they hunted. It is the same for the few remaining indigenous hunter gatherers around the world today and it is no different for the majority of conscientious deer stalkers.’’

We’re disconnected from the food we eat, never more so than with meat. I’m aware that some of you will feel distressed seeing bodies of animals in this piece. It’s one of the reasons, as I said to my mother, why I wanted to look the meat I eat in the eye. And why I sat for the best part of a week around an open fire in a wood on Dartmoor last month, learning about the ways of the deer. Sharif shot one of the deer that was part of a course, Honouring the Sacred Deer run by Jessie Watson Brown of Oak and Smoke Tannery and Lucy O'Hagan of Wild Awake Ireland.

The course asks many questions including how do we become worthy of asking someone to die so we may live. How do we honour an animals life and their death and make beauty from their body.

Lucy is keen to point out that the course isn’t for everyone. ‘‘And that’s okay. Nobody should be forced to eat what they don’t want.’’ She adds;

‘‘From a perspective of reciprocity as humans living on this land, we have a responsibility to perform the role of the wolf, the predator. Not to get rid of all deer, but to be in relationship with them and all living things so that balance can be restored.’’

This links right back to what Dr Naomi Sykes says at the top of this article about looking for medieval solutions.

Beginning with the bodies of two recently shot roe deer, via ceremony and circles, the deer were honoured. We were taught how to remove their liver, heart, lungs and kidneys. Learnt to skin and break down their bodies, using flint tools. Butchered them into different cuts. Tanned the hide. Learnt about tracking, trailing and dear behaviour. Crafted using bone, sinew, antler and hoofs. Listened to stories about deer mythology. Explored our place in the web of life and gave ourselves time to be, to remember, to be in place in the woods, under the trees, in balance and harmony with the deer. To ask the questions; what are we doing here, what do we take away?

There were sixteen of us, including two vegetarians; brave and thoughtful men, open to the experience. David, a forest school teacher based in Devon doesn’t like anything to be wasted. He’s here because he believes that an animal should be respected. If its life is going to be given up, it should be used completely, without waste. On our first morning, he ate a little of our hunters breakfast; the heart, liver and kidney, the first time he’d eaten meat in four-five years.

We ate the deer; every day a different cut; on the open fire, slow cooked, marinated, stone pit, as Jessie and Lucy say; with deep respect, joy, gratitude and humility. A deep remembering, through bloodied hands, full bellies and aching hearts. To remember our place as hunters, as beauty weavers, gratitude gatherers and feast makers.

Jessie was inspired to work with deer because once culled, their hides are thrown away. She loves making use of what’s abundant and usually wasted. For her the course is about reclaiming ceremony, re-skilling people, and creating a space where people can come face to face with death, and with that, responsibility, accountability and the impact our lives have.

It’s an important awakening to understand the life, and death of the food we eat and give honour to that experience. I learnt a great deal, including patience, and came away wiser and more connected to the land and more grateful than ever for the wild deer that provide us with nourishment.

Be More Wolf.

Where to buy wild venison

Rather than buying from farmed or imported supermarket venison, check your nearest farm shop, butcher or farmers market for local and wild.

Billy Wyatt and co started the Facebook group Giving up the Game to try to encourage people to buy wild game directly from the stalkers.

Plenty of stalkers have their own websites where you can order directly, such as

https://venisonadvisory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UK-venison-market-June-2019.pdf

I learnt a new word. gralloching the deer, I’d only known the word paunching, mostly from English folk songs about poachers. Gralloch is Gaelic for intestines and refers to the process of disemboweling a deer in the field once it’s been shot and killed.

Thank you for all the work you did on this important topic. I am from the Midwest USA, where hunting deer is a specific season and not all hunters get the single deer they are licensed to shoot. Of course that means they are highly valued.

It’s amazing to me that there is such an overpopulation in the U.K., and tragic that they cannot all be eaten and used. More people should be learning how to break down the animal and use as much as possible - there is amazing sausage and leather wasted. But as you say, we are very far removed from our food, unfortunately.

Thank you.

I love venison and cook and eat a lot of it - and as for how close I am to it at any time, there are a lot of muntjac where I live, which is a small market town in the Midlands. Even so I was surprised to be nearly bowled over the other day by a roe deer running full tilt down our street at 06:45 as I was heading out for a run.

As regards halal, it's my understanding that the hunter needs to say a prayer as they take the shot. I could be wrong, but it was a subject that came up for discussion on a Facebook group (Giving up the Game), that exists to unite people who want game meat with people who can provide it, quite often for free. Everyone that did comment from a hunter's point of view said this was the case.