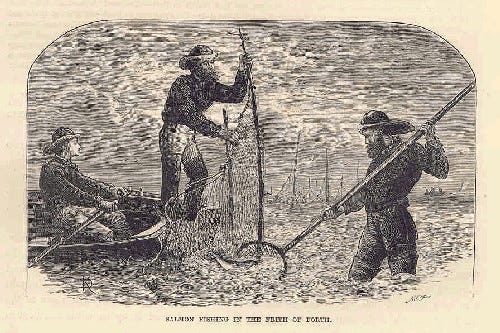

The word Salmon comes from the Latin word for leap, Salar, conjuring up graceful, exhausted fish, leaping upwards into waterfalls on their way to their spawning grounds. Sadly the majority of the salmon that we eat don’t do much leaping.

Farmed salmon is one of the UK’s largest food exports.1

Fish farming is the fastest growing animal based food producing sector in the world. Aquaculture provides more than half the fish we eat.

The majority of salmon farms are owned by companies based in Norway and Canada. Marine Harvest; the largest fish farming company is a Norwegian owned multi national, producing around a third of Scotland’s farmed salmon.

Farmed salmon begin their life as eggs grown in trays, after 60 days, they hatch into alevins. 4-6 weeks later once they've reached the stage where they can feed themselves, they're known as fry. For the next eight-ten weeks of their lives they're fed in growing tanks. The juvenile salmon go through a transformation from parr to smolt in a process called smoltification, where the salmon are getting ready to adapt to the life in sea water. Before the transfer to sea water, the smolt are vaccinated. They’re transferred to freshwater loch cages or bigger tanks in a recirculation plant.

Once they've grown to size, after one-two years, the salmon are brought back on land, stunned, bled, packed and transported to processing plants.

According to Salmon Scotland, the earliest recorded effort to incubate and hatch salmon eggs took place in 1838.

This accelerated during the Victorian era with eggs and juvenile fish cultivated to restock rivers. By 1890 there were 18 hatcheries operating in Scotland.

The first marine fish farm was established at Loch Ailort in Inverness-shire in 1965.

At the first commercial harvest in 1971, 14 tonnes of farmed Scottish salmon were sold. By 2015 salmon had become the largest food export in the UK. Most salmon eggs are imported, mostly from Norway, Ireland and Iceland.

WildFish2 has recently released a new report that shows Scottish farmed salmon is being marketed in such a way that consumers could be misled as to the origin, welfare and environmental performance of their purchases

Their report states that;

Mowi, the world’s largest salmon farming company and supplier to Tesco, ASDA, Sainsbury’s and the Royal Household, reported almost 5 million farmed salmon deaths on its farms in 2023. It also used 1.3 million litres of hydrogen peroxide across that period. Between 2018 and 2023, the company has doubled its use of the organophosphate pesticide azamethiphos.

Loch Duart, marketed as higher welfare premium salmon served at the Downing Street Coronation lunch in 2023, breached sea lice levels on more than one third of its farms in 2022. They also reported using over 41,000 litres of hydrogen peroxide in 2023.

Farmed salmon escape from farms, spreading diseases, and parasitic sea lice which graze on salmon skin and mucus. The salmon interbreed, compete with wild fish for food and impact eco systems.3

Farms operate in beautiful pristine surroundings, but create dead zones4 where their once their rich biodiversity dies. Areas on the ocean floor with little or no oxygen, where life cannot thrive.

Antibiotics used in fish farms have a negative effect on wild fish and sea creatures.

Farmed salmon are fed pellets made from other species of fish. Lex Rigby from Wild Fish stated that it takes as many as 440 fish to produce a single farmed salmon. These fish are taken from natural habitats around the globe, reducing biodiversity and damaging local ecosystems.

As the Sustainable Restaurant Association points out, many of the wild fish used as feed are sourced from countries in the Global South, which is highly problematic in terms of food sovereignty and food security.

On average, one in four farmed salmon die before ever reaching the consumer. In Scotland, for example, over 25% of Scottish farmed salmon die prematurely – over 16.5 million in 2022 alone. Orkney News quotes a mortality rate in 2024 of 17.4 million.

If sea lice cover a fish, they can die. In 2011, 35 medicines were licenced to keep salmon clean. Online report Marine Harvest found that at a fish farm in Torrridon, an outbreak of sea lice in 2015 was 20 times the recommended limit.

More than 350 chefs, restaurants, community groups, charities and NGOs are supporting WildFish’s Off the table campaign, which asks chefs and restaurants to take farmed salmon off their menus.

Is there such a thing as sustainable salmon?

Caroline Bennett is founder of Moshi Moshi Sushi, the first Japanese rotating sushi bar in London, one that really cares about their sourcing, and Sole of Discretion, a community interest company, they buys exclusively from low impact, small scale vessels in and around Plymouth.

I'm meeting Caroline to talk about farmed salmon. I think it's fair to say that we have known each other for many years and I'm always impressed by her depth of knowledge about fish. I’m a little early when I arrive; Caroline is in an online meeting with fishermen, discussing the idea of electric boats. It's getting heated, so she logs out.

I ask firstly, what's the problem with eating farmed salmon?

Caroline;

‘‘There are myriad problems. From an environmental point of view, the farms are often in pristine, precious waters that are very vulnerable to disturbance. So the impact on the marine environment can be really damaging. There's also the pollution aspect of a fish farm.

‘‘They put a lot of pollutants into the water which contributes to that damage, damaging the seabed for example. When I was last up in Loch Duat, they had a machine that was basically running up and down the nets to try and get rid of the debris, foulants so that's a good step. But the machine was deafening above sea level. Imagine that sound for a fish underneath it. The headaches those fish must be getting.

‘‘Plus, of course, all the sonar that must be disturbed by the passing orcas. The biggest environmental aspect for me though is not on our own doorsteps. And for me, this is the biggest problem because one of the things the industry is looking to do is to put farms on land5 and then obviously you negate some of the problems we've been just discussing. But the biggest issue for me is the fish feed.

‘‘The amount a carnivorous fish will eat depends upon which farm you talk to. Back in the bad days, 12 kilos of fish, wild caught fish, would create just one kilo of farmed salmon. Now because of the price and the relative status of fish stocks going down worldwide, the industry has managed to pair that right down. They say they’ve got it down to one to one. So a kilo of wild to a kilo of farmed.

‘‘I'd say that was pretty unlikely and there's always this issue of, are you comparing wet fish to dry fish? Because, of course, a kilo of dry fish meal is probably only a third of the weight of the original weight of the wet fish. So there's always those smoke and mirrors and they're never offering that as a clear answer. It's always a bit hidden. But this fish meal doesn't come from algae.

‘‘It’s not a like a cow or a sheep, eating grass to turn it into an animal protein. These carnivorous fish are eating other fish to turn themselves into delicious tasting salmon. And these fish invariably come from impoverished developing, world countries, particularly Mauritania, Ghana, Chile, Indonesia, The Philippines, all the poorer countries where their own people are so self reliant on the local fish stocks doing well, for a food source.

‘‘It's not just for, oh, do I fancy a nice piece of salmon today? It's that's the only protein many of them will will ever have, the animal protein at least. So essentially to me, salmon farms are robbing the poor to feed an already overly wealthy, overly nourished West. And morally it's really abhorrent. I just don't see how even better farming, bringing it on land can ever square that circle.

To a consumer who’s in a supermarket and they see a nice piece of cheap salmon, why should they care? What would stop them from from buying it?

‘‘Well, I'd start with taste. But, hey, that's me. It's one of those things that you get used to.

‘‘I never used to eat dark chocolate as a child. But my goodness, I can't eat milky Cadburys any longer. I want my dark chocolate. So a lot of it is taste, and it's what you get used to.

‘‘The nutritional benefit of eating a farmed salmon is so much negated compared to a wild salmon. It's infinitesimally poor by comparison to the wild. Then, there’s all the NHS recommendations to eat two portions of fish a week, there's no point eating that salmon. All it's doing is giving you the high fatty acid, the wrong types of fatty acids. So it's not giving you the nutritional benefits. It's not got anything like the same minerals and vitamin content.

‘‘So, yes. Why do you eat salmon in the first place? If it's just the taste, then it will be a transition I would say. And the wild fish tastes so different. It's meatier.

‘‘It's often a bit drier because they've used so much muscle to navigate the seas. Whereas, the farm fish have flabbed around in a swimming pool being fed Amazonian reared palm oil, and that's their diet and it's not really a natural diet. As fish stocks have dwindled and fish has become extremely expensive to put into fish meal, they’ve substituted with cheaper things like palm oil. That's another reason why perhaps you might not want to eat farmed salmon. There are so many reasons why you might want not want to eat farmed.

I remember last year when we were talking about the Off the Table campaign, you'd said that you were trying to work with them to get a month of ‘No Farmed Salmon’ in the City.

You were hoping to offer a standard, a choice between farmed or wild salmon. And you said, I'm just ashamed still to be serving farm stuff.

‘‘That has been an aspiration for many years. To put it into a cultural historic context, Japanese food and sushi in particular never had salmon in it traditionally. It was only with the advent of farmed salmon that salmon became the ubiquitous fish in sushi that you see now. So if historically you were looking at using salmon then you didn't have anything to go by.

‘‘It would be lovely if people diversify from eating salmon full stop. Wouldn't that be great? Like we ate more of the 50 species that we catch pretty much daily in Plymouth, rather than focus so heavily on just this salmon. So that's one aspect.

‘‘So then so I think, well, okay. Let's let's see if we can take farmed salmon off the menu and put wild in. So we've made our first steps and my goodness how long in the making it's been.

‘‘In 2019, I went with the Slow Food crowd to Alaska, and I met a couple of the fishers out there. There are 5 different salmon species in Alaska, two are suitable for eating raw, for sushi.

‘‘The big difference now is that we can freeze them. They come over as whole fish by sea. It takes, from us thinking about roughly what we’re going to want to sell next year. We then tell the fisher, he’ll fish from May to the end of September and he’ll be phoning, keeping us informed. Eventually we get the final order into a shipping container, and it arrives December/January. So what we’ve started planning now doesn’t arrive for the best part of a year.

‘‘Then, the fish are so large that we don’t have the fridge space to store them. So we have to think about means of accommodating these very different fish.

‘‘If you order one of our lunchtime sushi sets, in the restaurant it will automatically come with Alaskan wild salmon unless you actively specify you want farmed. And for that privilege you are charged an extra 50 pence. I’m trying to actively dissuade people from going for the farmed.

‘‘I would love to do that in more volume on the sushi counter and in our takeaways but because of the fridge space and our inability to take the frozen fish, that’s for the next round.

‘‘We are still using farmed salmon. Wildfish would love to promote us as being a sushi bar that’s not using farmed salmon and we’d love to do that, but until we crack these operational issues, I simply won’t be able to roll it out into anything bigger.

‘‘The reason traditionally they're not eaten raw is because that they're full of Anisakis parasites.

If you eat these Anisakis parasites what happens!?

‘‘You can get very ill! That is actually the skill of a sushi chef, to be able to look at a piece of fish and carve it and know whether it's fresh enough to be served raw. Anisakis is present in lots of species; cod has lots of it, hake has lots of it, monkfish has loads of it. So it's completely normal. It's a natural parasite. But once cooked, it's fine.

‘‘It doesn't affect you. But in Japanese cuisine, obviously, it doesn't go through the cooking process. I've got a fantastic woodblock print from a Tohoku medical library from the 1800’s with this massive worm falling out of the bum of this kimono clad man. Anyway, it gets quite exciting. You don't want to give people parasites and that's why traditionally salmon was never used. But with the advent of freezing, that turns it into a different parameter of what you could potentially use.

‘‘If they're frozen, this kills the parasites.

Are the public ready for a no salmon sushi bar?

‘‘No salmon. I think if you went to a higher end restaurant, absolutely you could do it. We have always tried not to be that high end restaurant. We've always tried to be something that's more accessible and more open to everyone. And therein lies the problem,.

‘‘If you're gonna rely on fish that aren't standard, we can always get in a salmon. Invariably, you need a chef that will be able to look at a species and go, okay, I know how to do that. You've got to change menus very regularly and you've got to have the skills to be able to fillet a flatfish etc. We have those skills here, but we just don't have the space or enough people with those skills to be able to warrant to do that on a wider range of species.

‘‘It's one of those business things, really. At the end of the day, it's all about money. What in an ideal world can we move towards without breaking the business in the process?

Before salmon appeared on restaurant menus, as you mentioned, was there a fish that was as widely used that could still be used again?

‘‘I would say probably not.

‘‘If you went to a Japanese restaurant or a Japanese traditional sushi bar, you'd have maybe 15 different species in one sitting. We simply don't get 15 different species that are available for sushi, in this country. And if we did, they'd be no more environmentally sensitive than some of the farmed salmon. And that's the problem. There are only a certain number of species that you can get, that you know are caught in an environmentally sensitive way.

‘‘We could start going down the lines of unagi, for example, river eel, a critically endangered species, but still very prevalent and available in Japanese restaurants. We could go down the prawn route. We do have prawns, but they're very difficult to come by where they haven't been dredged from the North Sea or from a mangrove in a tropical country. So there are so many issues. And just by taking farmed salmon off a menu for a sushi restaurant, you just raise the question of, well, what then do you replace it with?

‘‘We are eating way more fish as a global population than there are fish to environmentally sensitively support that. So it's one thing for a conventional restaurant to say, yep, I'll take farm salmon off the menu and and I'll replace it with a delicious lentil dish. You just can't do that with sushi, and that's the problem.’’

What do you look for when you're sourcing farmed salmon? What should a customer in a supermarket be looking for?

‘‘That's a really hard question. I mean, I think twenty, thirty years ago when we first started buying, for example, Loch Duart salmon up in Scotland. We went to visit them and we met the two founders, local people with a vision that they wanted to create quality salmon. Over the years; competition, all the problems of rearing fish ecologically more soundly, a bit like the organic standard where the density has to be lower, use of antibiotics…

‘‘They were very confident that they were going to be able to farm salmon to a different standard. They've now retired and it's been sold. One of the current shareholders is the founder of eBay.

‘‘So it's not even locally owned any longer. And what realistic interest would that founder of eBay have in maintaining the pristine waters of a Scottish loch. So that whole thing has moved on so far in terms of it being realistic to assume that one farm could be different from another. Nowadays, I've pretty much stopped trying with farmed salmon. The only thing we stipulated, it has got to be Scottish.

‘‘Scottish farming is possibly a little bit better than farming in Chile, which has far lower standards. But that's really all I could say about it. Compare that to wild fisheries. A Scottish scallop could be caught by a dredge, a really damaging, impactful hugely fuel intensive, method of catching a scallop. So maybe you'd rank that number one on a scale of one to ten. That's not great. Look at a Scottish dive caught scallop. Somebody's gone out in a dry suit in freezing waters to dive for the scallop. That's got the least environmental impact and probably the best social impact. So that you would rank a ten.

‘‘In the world of fin fishing, there's everything else in the middle. So you've got all these grayer areas of a netted or a trawled or a line caught or a potted. So you can have anything from that range of one to ten. Whereas with the Scottish salmon farms now, maybe Mowie is the worst at number one. And I don't even want to say that Loch Duat is necessarily the best any longer because I just don't know. But that would only ranks at number two. I don't think it'd even get to a three. So that's the level of difference that you're looking at. It's minute. They're all pretty rubbish.’’

Some farmed salmon is labeled as being organically reared and every Scottish farm comes under the Aquatic Stewardship Council. What would you say about those labels?

‘‘The Aquatic Stewardship Council, I compare to a red tractor standard. It's really a bare minimum. It’s not a gold standard, it sets the limits perhaps. And perhaps it was one of the organizations that fought against the heavy use of antibiotics, that kind of thing. But it's a bare minimum. And the organic standard, essentially is about stocking densities.

‘‘You can stock a pool of fish with fewer fish in it, which would in turn lead to less disease. Then you don't need to treat them with antibiotics or delouse them as often and that kind of thing. So it's a better welfare for the salmon. I don't know whether a fish notices that it's got 30% fewer fish around it or not, I don't know.

‘‘The point with organic salmon is the same as with farmed; their feed stock still relies on wild caught fish, and that in itself is a big stumbling block for any sustainability criteria in my view.

The ASC website seems to be very keen to emphasize, that farms must be socially responsible, and that includes being good neighbours. They say, local communities are even invited to have their say in potential ASC certification of nearby farms. They quote, ‘‘at ASC, we are for unlocking the full potential of fish farming, which goes beyond the already important need to feed a growing global population, and includes many social and economic benefits that they're trying to emphasize what their fish farms do for, especially for rural communities.’’ What do you think about that?

‘‘Loch Duart used to leave their nets fallow one year in three, to get rid of debris. They used to employ a lot of people to monitor the amount of feed. Fast forward twenty years, now that feed has been automated, so they don't need nearly as many people to make sure that the fish are getting fed regularly. We've already talked about those nets that were being decruded by loud machines. The number of people that they're looking to employ has actively been decreased.6

‘‘The industry will have you believe that there's an awfully large benefit to having locally employed people in rural places. If you could get the notion that without those fish pens, you could have shellfish potters or you could have inshore divers or you could have, you know, dare I even dream of inshore fin fishers if the stocks came back, or you could have whale watching cruises for tourism. So there's all these other number of things that the industry is essentially ensuring can't happen because they've got this monopoly on that area. And there's a sense, I think, amongst the community that you feel you can't speak out against it. You also feel very isolated: we don't really like this smelly fish farm on our doorstep, but I don't know what so and so two miles down the road who may be your nearest neighbour is thinking.

‘‘If a building goes up in Central London, it may get lots of opposition and people complaining that it's too high. In rural communities, they just don't have that clout. They're too dispersed. So I think for the industry to say that they engage with the communities is over egging it a little bit. But even if they do all that, it doesn't square that whole problem of the feed.

‘‘You and I in Slow Food have been there. We've seen people from Mauritania and Ghana and and the likes. I've met fishing families from Mauritania who were fishing sustainably for grey mullet. It's only a two, three month fishery all year round. So they come in, they spawn, and the fisher folk would go out in small pirogues to fish for this mullet.

‘‘They'd land it to the women who would dry it for the interior of the country. The botaga, the roe, would get dried and sent to Italy as their expensive export market. Essentially, they were feeding the entire community from this two, three month fishery. An entire coastal community was based around this small scale fishery.

‘‘And then EU vessels are buying out the rights to fish off the Mauritanian coast. And these are EU flag vessels going out there, buying up all the Sardinella quotas. There's no limits, and no such thing as a monitoring coast guard in Mauritania. So if they go into different areas of of the sea or if they take far more than they've agreed to take, there's nobody to police them.

‘‘Meanwhile, these poor guys are going out in their two, three month fisheries. And it's not only they find that there aren't enough fish left in the sea to fish because they've all been taken by these massive boats. It's also dangerous because they're in little wooden pirogues. These massive nets could literally lift them out of the water and they could die. So they're not even able to go close to where their original fishery grounds were. Over the course of twenty odd years that I've been meeting these people, that entire coastal community has just collapsed.

‘‘The women have got nothing to process and nothing to live off. The men are so desperate that they get on boats to Libya and they try to cross over to Europe as economic migrants.

‘‘Maybe the farmed salmon industry will go for the insect and worm route, which is potentially possible.

‘‘But until we can do that, there's no way that you can say that salmon farms are socially responsible. And for them to talk about social responsibility as being on their own doorstep, completely forgetting and ignoring the plights of the people that they're exploiting overseas, for me, is a completely morally bankrupt argument. And for that reason alone, could never be sustainable.

A 2016 United Nations report highlighted the key role aquaculture is playing in contributing to global food security. I found that on the, Salmon Scotland website, they say in a context of climate change, economic uncertainty, and growing competition for natural resources, UN member states adopted the 02/1930 agenda for sustainable development, which sees aquaculture as an essential part of future global food security. So my question is, could salmon farming help feed the world?

‘‘Are you trying to annoy me?! There are many things that you can farm responsibly.

‘‘Mussels are a fantastic example. If we just fill the seas with mussel farms, that would be great. There are lots of vegetarian fish in Asia, carp and tilapia.

‘‘But if you look at the conditions, they're grown in sewage works. There's no way I want to eat any of those. And the same would go for the salmon. If they can farm it sustainably using sustainable palm oil and and worms, then great.

‘‘I would then question why the heck would anyone want to eat that? Why wouldn't you just want to eat lentils and an apple for the evening meal? But I just don't see how the UN, if it's coming from the UN, who are supposed to be looking at developing as well as developed countries, can really say that that's going to be the solution. Even if you looked at Britain; If Britain didn't export 80% of its fish and the UK ate only what it caught, didn't export anything, we'd still have less than one and a half portions a week. So even Britain, a tiny island nation, is not self sufficient in its fishing.

‘‘Until fin fish can turn vegetarian, all we're doing is robbing the poor to feed the rich.

It’s lunch time. On the conveyor belt at Moshi Moshi, salmon is labelled ‘wild’. Caroline tells me that customers often prefer the taste of farmed salmon.

‘‘It’s habit. Wild salmon is dryer, leaner.’’

Yesterday Caroline told me that fish sales from Sole of Discretion to one of her buyers has dramatically decreased. Could it be, the buyer mused, that customers are getting the message about farmed salmon?

In 2023, Salmon Scotland sought and got approval from DEFRA to drop the word farmed from its protective geographical indication. The words ‘organic ‘ and ‘conventional ‘ were also removed as was the production method; farmed or wild caught, leaving the consumer none the wiser. In addition, the cage stocking density limit of 10kg per cubic metre was removed, opening the doors to an increase in infections and an increase in sea lice infestations.

Salmon Scotland fight back against what they call misinformation, in 2019 calling WildFish a ‘well funded but ill informed pro-fishing pressure group…masquerading as a conservation organisation when it is nothing of the sort.’ They also claim that salmon farming doesn't result in any significant harm to the environment.

They blame campaigners for wanting to take away a major source of rural employment.

On the issue of feed, they say that the main producers of feed for Scottish salmon now use trimmings from fish processing, unsuitable for human consumption, to make up almost a third of fish content. They go on…

‘Out farmers do not use feed which has ingredients from non -sustainable sources like India, Vietnam or The Gambia.’

On sea lice they state that medicine usage to treat lice has dropped by 49% because farmers are using different treatments like cleaner fish (wrasse and lumpfish) that eat lice off the salmon.

It doesn't say what happens to these fish.

In 2018, the Scottish rural affairs committee called for urgent action to improve the regulation of the Scottish salmon farming industry, and to address fish health and environmental challenges.

The Orkney Trout fishing association stated;

‘While production has rapidly increased, employment has not. The industry invests in capital, not people. Production continues to increase, adding to pressure on the environment. Increased automation, increased tonnage, increased pollution, but no significant increase in employment.’

Use of Wrasse as cleaner fish was discussed, as they're a keystone species in rocky reefs and kelp forests. Coastal Communities Network Scotland submitted evidence, stating that ‘the use of wrasse as cleaner fish, and then their slaughter is unethical. It should be halted.’

In January at the The Oxford Real Farming Conference, Rachel Mulrenan Scotland Director Wild Fish, Caroline Bennett, oyster farmer and Seawilding Co-ordinator Ailsa McLellan, film maker Francessco De Augustinis, and Chair Gina Lovett discussed the subject of sustainable salmon, and issues with salmon farms.

‘‘All of the profits get exported, all the pollution Scotland gets’’ Ailsa McLellan

Some of the points they raised included;

‘It may be a spectacular setting but it’s a factory farm’. Scotlands’ aquaculture industry is estimated to produce the same amount of nitrogen waste as the untreated sewage of 3.2 million people, just over half the countrys population.

More stringent rules and legislation wouldn’t make a difference because it's a fundamentally unsustainable system.

Our waters are getting warmer. Ailsa wants a momentum on growth. No more salmon farms until issues are sorted out. She talked about microplastics from feed barges being an increasing problem for both shellfish farmers and humans, as micro plastics make their way into the food chain.

In November 2024, an open letter was sent to the Scots Government7, signed by 50 organisations, asking for research and calling for cost benefit analysis. There is a huge knowledge gap, and it got a mention in Parliament. If they don't carry it out, Wild Fish will consider undertaking it.8

Mowie got £20 million for a new hatchery. That money could instead be used by small scale local businesses. Money is going to the largest players.

On certification, Rachel has researched them all. ASC, RSPCA, organic standards; none are high enough. They're all watered down to suit supermarket specifications, and impossible to enforce. They're too technical for many inspectors to understand, and many farms are remote and difficult and time consuming to reach. They rely on industry input, vested interest involved. Consumers believe something it's not representing.

Ailsa used to inspect for the RSPCA. ‘‘The more I saw, the less I liked it.’’ She was horrified by the waste, the culling. She gave an example of the ASC lowering the acceptable sea lice limits. ‘‘They're riddled with loopholes. Consumers aren't made aware of any changes.”

How do you feel about eating salmon? Is it off the menu, or not?

Scottish farmed salmon is the UKs top food export, worth £645 billion https://www.salmonscotland.co.uk/news/scottish-salmon-exports-leap-to-645-million-five-year-high

Off The Table, a campaign run by Wild Fish aims to take farmed salmon and trout off restaurant menus.

According to a recent article on the Inrafish website, ‘‘At least 42,000 salmon escaped from Norwegian farms in the first six weeks of this year, official data shows, a development that has alarmed authorities in the world’s largest salmon-producing nation.’ The number of escapes, the result of separate incidents on farms operated by Mowi and Leroy Scotland, is already more than 27 times the total during the entire year of 2023 according to data from the Norwegian directorate of Fisheries.’’

The concentration of organic waste, the feed that is not consumed, the faeces, floating plastic waste , toxic paint, chemicals, nets and sunken structures = dead zones. (The Global Salmon Farming Resistance).

Secret Smokehouse land based sustainable salmon

Salmon Scotland state that there are 2,300 people directly employed with a further 10,000 people working in the supply chain. Figures from the Scottish government say seven new people a year are employed.

I don’t eat fish but this is very interesting.

We stopped eating farmed salmon years ago but the shops are still full of it. Does boycotting really have impact? Hats off to anyone trying to use wild salmon but demand would exceed supply if we all tried it. I don’t know what the answer is - except to be vegetarian